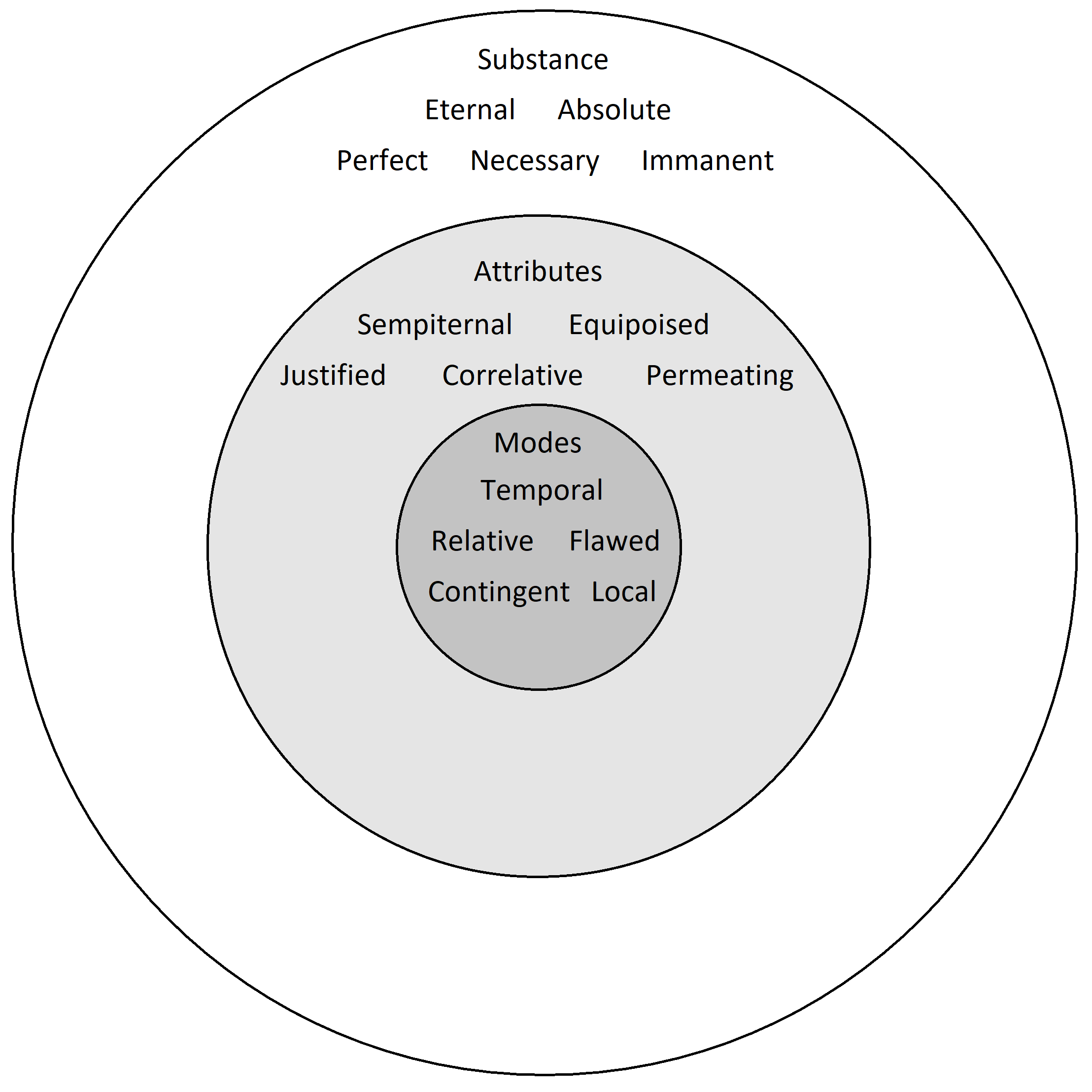

All that is, exists within God, whose mind and body is the very stuff of existence. As such, God has gone by various names throughout time, all of them imperfect. Among these are Nature, Substance, Necessity, the One, the Monad, the All, the Absolute, the Ultimate, Totality, Being, Existence, Essence, the Ground of Being, Reality, Mind, the Universe, Brahma, and etc. Zhe[1]— because neither male nor female, but both— is all-powerful, all-knowing, ever-present, and perfectly good, but ultimately transcends all contradiction, being unable to be precisely described or summed up in the confines of language, though able to be grasped as a concept, especially through metaphors and allegories or a comprehensive understanding of the Truth.

The Truth is that which corresponds to reality, meaning that there is a match between one’s notions and what actually is. When one knows the truth, one’s beliefs and the facts of the world are in agreement. For this reason, and for instance using a cut as a metaphor, an angled cut that is true is one that corresponds to the angle sought after, such that a cut is true if it matches the ideal. So, if the angle sought after is a 90 degree cut, and the cut is made at 89 or 91 degrees, that cut cannot be said to be true, as there is no correspondence. At least, it doesn’t correspond fully. There are, however, degrees of truth, meaning that there are things that are more true than others. For instance, the same 90 degree cut may not be perfect down to the level of the molecule, where certain aberrations are sure to be found. Nonetheless, it is approximately, or with the best accuracy achievable, true. This does not mean that a better approximation is impossible. A way to tell the likelihood of truth when correspondence is not available for checking is to test against coherence, or consistency with what else is known, so as to see if the information contradicts any information that is more sure. In an effort of critical thought, or considering information against more fundamental data, that which contradicts concrete knowledge (that which is sure by logical necessity) that is more fundamental must be rejected. God or Nature’s necessity is the most concrete, and any so-called information that contradicts this must be fundamentally rejected, for Necessity is the first of origin, without which nothing can be. That which is necessary, is, and from this fact everything flows. As such, depraved ideas such as pessimism, nihilism, postmodernism, absurdism, and so on, which reject Truth, must be put down.

While it was Thales who first proposed that the world was composed of a single substance, it would be Parmenides to first logically argue that this oneness is God, or Nature, and is eternal. This is not to say that God is infinite, though this is also so. Rather, it is to suggest that the Monad never ceases to be in any given point in time or space, but occupies all points in space and time at the same moment, something known today as superposition. Instead, it is us who shift coordinates within the Eternal, another name for God. Such a shift is not “really real,” but only occurs in God’s imagination, which is the same as the body of God, though it nonetheless highlights very real elements of Nature, and, as such, is certainly of reality, even if not of the fullest Reality. If you were to imagine a filament within a solid rock, and a light that traverses this filament, such an imagination would be similar to the nature of our illusory, separate existence within the Monad. This filament, however, in taking place in God, and so in traversing a part of God’s being, however imaginally considered, is nonetheless a part of God’s necessity, each filament highlighting a portion of Necessity such that each individual is themselves coextensively necessary (even if not in a self-sufficient way).

Despite the unchanging nature of Eternity, and following common sense, such as that Thomas Reid defended, we see change, despite the claim that our existence is semi-illusory, and taking place in an unchanging Monad. All change can be reduced to fluctuations within two categories, which, themselves, function in parallel according to correspondence, or equipoise, as Ramon Llull suggested, and transformation, or turning one into the other, as Pierre Teilhard de Chardin and John Wheeler, among others, have pointed out, depending on the perspective taken, be it sempiternal or temporal.[2] The sempiternal, is the eternal cycling or oscillation between convergence and divergence, an interrelationship, perhaps, first acknowledged by Anaximenes from the evaporation and condensation of the water cycle, or perhaps by Empedocles or Heraclitus. The sempiternal both composes and is composed by the body of the Eternal, consisting of its dual attributes of modal categories, Baruch Spinoza’s Thought and Extension, which anchor non-dually into the Absolute of Nicholas of Cusa as a coincidence of opposites. Within the sempiternal is found the duality in Nature, the roots of Empedocles’s Love and of Strife, and of the Destiny and Fate exclaimed by Heraclitus, also acknowledged by the more ancient poets and prophets such as Zoroaster and Hermes. Love is the final attractor and the path to the Destiny to which all are unifyingly pulled, contrary to the repulsive Strife, which otherwise pushes us further apart, leading us to our Fate.

While the Eternal is the seat and stuff of the natural order, the unchanging structure of Nature, sempiternity is the seat and stuff of natural law, the natural flow of all subsidiary natures. Natural law is not itself the natural order, but is the manner by which we traverse the natural order. Whereas the natural order gives initial or orginal expression to sempiternal correlation, natural law provides causality, which refers to the chain of causes and their effects, whereby one thing, through an exchange of energy, can affect another thing. Causality is often understood through principles, which are statements regarding the effects that can be expected from certain causes. All of causality charts its course within the Eternal according to the correlations and transformations of sempiternity. Given that all causality can be reduced to two attributes of Nature, the world of Extension follows physical-mechanical laws, while the world of Thought follows the spiritual-moral laws. Perhaps the most important statement of the natural law as a whole is what may be understood as a self-referential statement extrapolated from Nature: “Know me and do well; forsake me and suffer!” Indeed, it is the Greatest Commandment of the ten that God gave to Moses, as Jesus tells us, saying of it that we must love God with all of our being. Those who do not learn the natural law suffer as a result, for to know God is to know the causes of things, or at the very least that there is a cause, or reason, for everything, which helps us to fare well in life. Those who act with an understanding of causality, act according to or with Reason, for causality is nothing more than the reasons things happen, their causes.

Mental noumena, the stuff of our minds, such as our thoughts and intentions, operate in parallel with physical events following the deterministic and probabilistic physical and mechanical laws of Extension, but are governed by spiritual or mental and moral laws of Thought teleologically—that is, from the future— instead, as Aristotle has clearly demonstrated, and toward Goodness, or Love, as Thales suggested, and including Truth and Beauty as Plotinus adds (as reconciled in the Source, that from which we came and to which we will return). Human action is not merely determined by external factors, that is, but is motivated by inherent purpose. Purpose is a force of teleology, a direction toward specific ends or goals, themselves giving certain forms to matter. When you engage mindfully in goal-directed actions, you behave purposefully, and, in doing so, introduce order into your environment, as aligned with your goals and intentions. Syntropy, the increase in order or organization within a system, as described by Luigi Fantappie, is associated with the final causes or teleological processes of the purposefulness in human nature. Syntropy, teleology, and purpose are associated with the attribute of Thought, that which can be imagined, intellectually conceived, and qualified.

On the other hand, material phenomena are governed by physics and mechanics, which are covered under the attribute of Extension, that which takes up or occurs within a given area. Entropy, or decrease in order, as described by Lazar Carnot and Rudolf Clausius, is typically associated with efficient causes or deterministic physical processes, such as those described by the Second Law of Thermodynamics, formalized by William Kelvin, and with a lack of information, as posed by Claude Shannon. Entropy leads to increased disorder or randomness in the abse nce of external intervention, and corresponds to a lack of purposeful action or of short-sightedness in one’s purpose. When things are neglected or go unconsidered, accidents and losses can occur, and things fall apart, becoming disordered. Entropy is mainly an unconscious process because pure entropy would be too excruciatingly painful for consciousness to endure. John Rawls’s Theory of Justice has shown that the best and most rational initial condition for an aggregate of consciousness entering into a novel situation in which each individual experience will have a different lot, is to establish rules of equal liberty such that, as the program plays out, the worst off may still see a gain in their happiness rather than be made to suffer. Seemingly true to this, syntropic processes are conscious, and, while it occurs in an entropic environment, it is itself increasing in pleasure, such that each generation tends to experience a relative increase in pleasure. The experience of skipping the pure process of entropy means that consciousness comes into being through acts of Creation, or punctuated equilibrium, which interjects changes into the world of entropy through living systems. This is no more than a syntropic process functioning in aggregate. Nonetheless, entropy does still fall into our range of experience, particularly where information is absent.

nce of external intervention, and corresponds to a lack of purposeful action or of short-sightedness in one’s purpose. When things are neglected or go unconsidered, accidents and losses can occur, and things fall apart, becoming disordered. Entropy is mainly an unconscious process because pure entropy would be too excruciatingly painful for consciousness to endure. John Rawls’s Theory of Justice has shown that the best and most rational initial condition for an aggregate of consciousness entering into a novel situation in which each individual experience will have a different lot, is to establish rules of equal liberty such that, as the program plays out, the worst off may still see a gain in their happiness rather than be made to suffer. Seemingly true to this, syntropic processes are conscious, and, while it occurs in an entropic environment, it is itself increasing in pleasure, such that each generation tends to experience a relative increase in pleasure. The experience of skipping the pure process of entropy means that consciousness comes into being through acts of Creation, or punctuated equilibrium, which interjects changes into the world of entropy through living systems. This is no more than a syntropic process functioning in aggregate. Nonetheless, entropy does still fall into our range of experience, particularly where information is absent.

Our modal and mortal existence, governed causally by sempiternity, takes place within the realm of temporality, the duration and sequential change of time early described by Heraclitus. This is the seat and stuff of plausibility, that which works according to causality, but which does not surely occur. Unlike the Eternal, which is unchanging, and the sempiternal, which forever cycles between the attributes of Thought and Extension, the temporal, which takes place within both of these, extended between Fate or Hate and Destiny or Love, is linear, moving from past, through the ever-pervasive present, and into the future, providing us a modal, mortal existence, being also local, or restricted to a given event, and contingent, dependent upon the causal factors of space and time. As such, temporalities, contingencies, and localities are isolated to particular events or sequences, which, unlike the Absolute Perfection of Substance, are themselves relativistic and modally flawed. Contingencies are reliant upon spacial-temporal coordinates, or ordinations, within the spacetime of Eternity, as particular events, and according to the occurrences of the sempiternal. As a reflection of the Monad, however, the temporal Universe displays the First Law of Thermodynamics— perhaps first described by Anaxagoras in his reconciliation of Heraclitean flux with Parmenidean permanence, but formalized much later in Isaac Newton’s conservation laws, and especially by James Joule—, which holds that nothing can be created or destroyed, though things may change form (such as by losing concentration of energy).[3] As such, all of the matter and energy in the Universe has existed and will continue to exist for all time, despite its temporality, locality, and contingency, and is interconvertible. And so time must cycle, owing to the limited combinations that can occur with a finite amount of matter and energy; a finite amount of stuff, that is, limits time from being infinite, except through recurrence. It is this inevitable durational repetition that emerges sempiternity from out of temporality, itself “emerging” Eternity.

Sempiternity, as it turns out, is that between temporality and eternity. As such, it has elements of both to it. From a temporal and reductive perspective, then, sempiternity appears as if contingent and dual, because it is the difference between past and future, and the forces of Fate and Destiny, relative to the individual. However, extrapolating the “perspective” of the Absolute, it would seem that sempiternity is again monistic, or described as a oneness, because the future becomes the past and the past the future, as it regards the teleonation of Destiny and the determination of Fate. It is in this way that there are elements both of correlation (reduction in entropy equals increase in syntropy, and vice versa) and transformation (the future becomes the past), too, which can be rationally picked up on from our standpoint in temporality. It is through the eternal and sempiternal that the temporal makes its eternal return, or repeating existence, as affirmed by Pythagoras, and in this maintains a timeless and everlasting— though less absolute— existence of its own, an everlasting life.

The “stuff” of temporality has been described variously. Empedocles, in addressing the conflict between Parmenides and Heraclitus, resolved that there were four elements— among them Thales’s water, Heraclitus’s fire, Anaximenes’s air, and adding his own, earth—, which Love and Strife, of course, mixed and separated. Anaximander thoughtully held that the various substances were subsidiary to a more fundamental one, of which each was an expression, and that they were all interconvertible. Similar to Empedocles and Anaxagoras, and perhaps contemporaneously, Leucippus desired to address the conflict between Parmenides and Heraclitus, and did so by maintaining that there was a void and that there are atoms that partially fill it, a view continued by Democritus and Epicurus. Aristotle, who rejected the void of the atomists and embraced Empedocles’s four elements as infinitely divisible, follows Anaximenes in his notion in his idea of prime matter. Along with efficient causation and final causation—effectively entropy and syntropy—, Aristotle gives two other “causes,” matter, the things, and form, the shapes they take, suggesting, like Anaximander, that the various kinds of matter can ultimately be reduced to his prime matter. Of course, for Artistotle, matter is more related to efficient causation, while form is typically given by final causation, and in this way Aristotle’s view is relatable to that of Anaxagoras, who held that Mind, or nous, acted on matter to give it shape, an idea Plato, Aristotle’s teacher, seems to have followed. Artistotle held that energy was any active quality, including emotive ones such as happiness. His views on form, or shape, come in part from Plato, who had held that there were ideal forms that were the causes which give the world its effects, and that the elements of the world were imperfect shapes. Giordano Bruno, an eclectic inspired by the astronomer Copernicus, finally declared that Aristotle’s notion of the sempiternity of the solar system was wrong, and Isaac Newton and many others, following after Giordano Bruno, would formalize energy into its physical definition, as having to do with electromagnetism, heat, and work.

This classical system of physics and mechanics, however, was seemingly disrupted by the development of relativistic and quantum thinking coming from out of studies of energy, following after Roger Boscovich’s reworking of Bruno, for instance, and especially after Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr, among others, suggesting that atoms are composed of smaller “point particles,” that there are no absolute locations in space and time, and that matter “pops into and out of existence.” This was later refined by people such as Luigi Fantappie and Paul Dirac, among others, into the model here presented, which affirms that syntropy acts teleologically to provide matter with a form and purpose within Eternity, but that, due to the future being invisible to us, this appears to occur at random and to “pop in and out of existence,” like forms on Plato’s cave wall, establishing temporal ideas such as those of uncertainty and probability. Plato had argued that the forms of the world were caused from elsewhere than the material Universe, and gave an allegory of men who are imprisoned in a cave and whose only visual reality is of shadows moving on the cave wall, having no other light source to see their surroundings with. According to Plato, our existence is similarly caused by such sources, effects having their causes in another area of existence that we cannot directly perceive. Aristotle had long argued that life was different from non-life due to its having an intrinsic, or internal, purposiveness. For Aristotle, that is, life is internally-directed, receiving teleological—or future—forces that compel it to preserve itself and increase its wellbeing. Non-life can be compelled by future forces, too, but only extrinsically, or externally, from outside of itself, by being given a purpose by a living thing. So, while a human being may be driven by internal purpose, a table created by a person receives its purpose from its creator. The human being, that is, in seeking to preserve their life and increase their wellbeing, creates the form of a table from out of the matter of the Universe, the wood, using the efficient causation of craftwork to achieve the demands of final causation, that there be a spot to place their dinner. The “final causation” and “forms” of Aristotle may be seen as a development of the causes of Platos “forms,” which Aristotle seems to have refined. The will of living things to stay alive and increase their wellbeing, Baruch Spinoza would come to know as conatus, or striving. Erwin Schrodinger would identify this living force with negentropy, or “negative entropy,” which he equated to the “free energy” of Josiah Gibbs. Of course, Fantappie, Szent-Gyorgyi, and others, such as Buckminster Fuller, would come to know this under the name syntropy. Gibbs’s free energy, commonly associated with that free energy also of Hermann von Helmholtz, is typically understood to be that energy that is available for performing work— that is, of exerting energy onto other bodies such as to force a change in them—, and, in living things, is that caloric energy that stores from out of processes such as photosynthesis and metabolism, and which is released in a stochastic fashion, meaning that it is unpredictable and non-mechanical, having no efficient cause for a simple explanation. Free will, as a result, is a subject of much confusion and, by extension, much contention. It is certain that humans have wills, but the point of contention is whether it is free, unrestrained, or not. In the most concrete sense, the will is not free, because it is the expression of the sempiternal battle between physical determinism and psychical teleology, being an instance of purposiveness, to the extent one’s destiny is claimed and one’s fate is not resigned to. But there is a sense in which the will may be said to be free, and that is in the sense that it is not subject to absolute mechanical causation, and so in this sense it may be said to be “free” from physical absolutism, though it is still not free in the sense of one being able to “will what one wills,” as Arthur Schopenhauer put it. All of our temporal philosophies, as a result, can be reduced to idealism or realism, and inhere in Thought and Extension, or else are nominalistic and incline to nothingness, such as Schopenhauer’s pessimism.

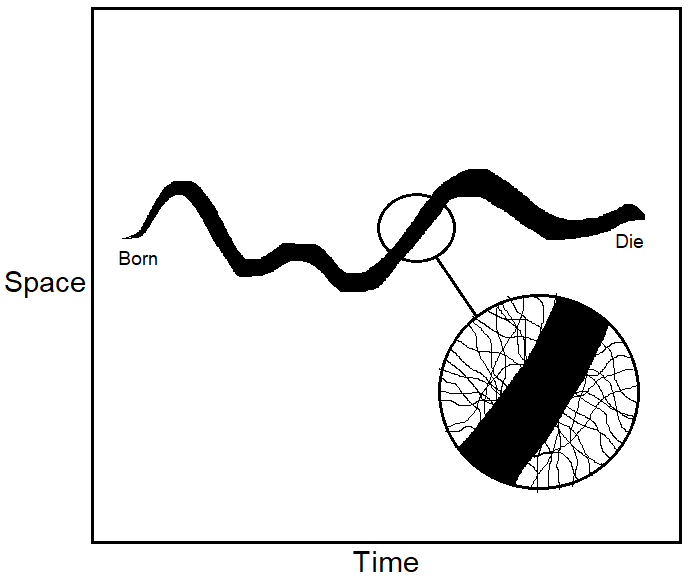

The filament-like paths that each of each of us temporally traverse in the eternal Universe, extending from one’s birth to one’s death, is known today as a worldline or time worm, first described by Hermann Minkowski and expanded upon by John Wheeler. This wordline is not at all on its own, however, but is actually connected to the rest of existence. While it may have a bodyform of its own, in the form of a line, upon closer inspection this line is more like a braid or tangle which continually incorporates and rejects strands of material as one syntropically takes in material and energy, or entropically lets it out. As such, the material that one is composed of has composed other entities,  and, when gone, once again joins the body of another, tying all of us together as we breathe the same air and partake together in the nutrient cycles of the ecosystem, exchanging atoms throughout our temporal existence. The stuff of our bodies, the nitrogen, carbon, minerals, oxygen, and water cycles in and out of us, and is ultimately interchangeable. And our time worm, as a result, is a “hairy” one. John Wheeler suggested that such a hairy timeworm might result from a one-electron Universe, a Universe the structure of which is like that of a one-line drawing, where one does not remove the pen or pencil from the paper. He suggested that if a conical section were to be taken from such a tangled worldline, that anything to the relative causal past would be considered regular matter, whereas that which is in the relative future would be considered anti-matter, the opposite of matter proposed by Paul Dirac, but that these are ultimately one and the same. They are known, in wave form, as advanced and retarded waves. As ideas such as pessimism, postmodernism, absurdism, and the like, are based on the world as understood through witnessing retarded waves, these views may be properly called retarded views.

and, when gone, once again joins the body of another, tying all of us together as we breathe the same air and partake together in the nutrient cycles of the ecosystem, exchanging atoms throughout our temporal existence. The stuff of our bodies, the nitrogen, carbon, minerals, oxygen, and water cycles in and out of us, and is ultimately interchangeable. And our time worm, as a result, is a “hairy” one. John Wheeler suggested that such a hairy timeworm might result from a one-electron Universe, a Universe the structure of which is like that of a one-line drawing, where one does not remove the pen or pencil from the paper. He suggested that if a conical section were to be taken from such a tangled worldline, that anything to the relative causal past would be considered regular matter, whereas that which is in the relative future would be considered anti-matter, the opposite of matter proposed by Paul Dirac, but that these are ultimately one and the same. They are known, in wave form, as advanced and retarded waves. As ideas such as pessimism, postmodernism, absurdism, and the like, are based on the world as understood through witnessing retarded waves, these views may be properly called retarded views.

Entropy and syntropy are both at play in our wordlines. When you engage in syntropic goal-directed behavior, such as by getting up to make food to sustain your life, your mind is directed by purpose, while your body’s actions are governed by physical processes, which are entropic. Thus, your actions can be directed towards reducing entropy overall, even while entropy is still occurring,[4] resulting in Erwing Schrodinger’s negentropy. While your body follows the physical processes, your goal-directed behavior introduces a teleological aspect that guides your actions towards reducing disorder and increasing order in your environment, as was affirmed by Albert Szent-Gyorgyi, who proposed that Fantappie’s syntropy again be used rather than negentropy. By replenishing your energy and sustaining your existence, your actions contribute to reducing your entropy overall, or macroscopically, even as they may involve entropy increase at the microscopic level (such as by cellular damage and heat expenditure),[5] and even further an immediate increase in entropy in the environment, owing to waste (which in the long-run is bio-recycled and actually is not so entropic after all, though the environment may also become more ordered, and so negentropic, thanks to your syntropic arrangements). Negentropy, or syntropy, is still at play, and especially where nous makes its plays.

Both physical, mechanical determinism and mental, moral teleology operate according to Necessity, “requirement,” or Natura naturans,[6] Spinoza’s term for Nature as an undivided and essential whole. Necessity gives way to particular natural laws, and these particular natural laws, which regard mortal existents, express secondary nature, or Natura naturata,[7] his term for Nature in its temporal particulars (which nonetheless inheres in Natura naturans). Human nature is an expression of Natura naturata while God’s nature is that of Natura naturans, the same as God’s being. God’s being, that is, is synonymous with God’s will, and this provides the structure of space and time, and the corresponding laws, in and according to which all mortal existence takes place. All that is done is done according to the will and through the body of God, Nature, or Necessity. What God wants is done, being a requirement of all subsidiary natures. Nothing can contradict God.

Not all that is done is fruitful or longlasting, however. All mortal things have an end, and that is why they are contingent. And it is in this way that the past and future will of God can be discerned to some limited extent, for, temporally speaking, and as Giordano Bruno made blatantly clear, that which God wills is that which is and will be, and that which God has already willed is that which has come to pass.

Regarding the Good, which may be known as proximity to God, it comes in many forms. Basic goodness, or satisfaction, is capable of being in conflict with others’ notions of goodness. For instance, the hunt is good for the lion and bad for the gazelle. This is a lesser sort of good, because also bad. Greater goods, those which are of a higher order, result from agreement about what is good, but may still be bad to a lesser extent, while the Greatest Good is that which all can agree upon, and which is not bad, but which is known as the universal, being everywhere applicable. The Greatest Good is often seen as synonymous with Perfection, or flawlessness, and there are reasons for this. Something is perfect when there is nothing better that can be put in comparison to it. God is absolutely perfect, because there is nothing outside of God with which to compare Zhim. God is incomparable, and so is perfect as a result. And, in fact, us mortals reflect this perfection to some extent, in that we are each unique, and in our uniqueness are incomparable to others, each being perfectly themselves. Our imperfection, then, is not innate, but only exists when compared to others, and in this we are all imperfect. However, Perfection transcends the Greatest Good by allowing for the Best, as well, in this case the Best Possible World, which has just enough badness in it that the Good can be known in contrast; for, to know white we must know black, to know hot we must know cold, and to know good we must know bad. Perfection, then, especially in the cosmic sense, includes also the “flaws” of the contingent world, to the extent that they allow the Good to be comprehended, and this is the extent to which flaws exist.

All of that which God wills, and nothing that God does not will, is, as God is perfect in Zher being and in Zher wants. That is, for God, the subjective and the objective are synonymous, such that what is subjectively desired by God objectively is. This is what it means for God to be all-powerful and present everywhere. And so God decides what is and is not to have a mortal existence, and for what duration. And God’s judgment in this regard is always good and always right because it is always absolute and perfect. It is good not because it pleases humanity, but because it pleases God; it is good because God is satisfied by it, and Zher’s is the only opinion that ultimately, and literally matters. Thus, God’s perfect goodness is unquestionable. And so that which is for some time necessary is not itself the Necessary, but is contingent upon place and time in the body and judgment of God.

Eriugena held that God is responsible for creating humans and for giving them free will, but that what humans do with it is up to them. While flawed in his details, a better construct can be derived from the sentiment, that the realms of the Eternal and the temporal must be kept philosophically separate, such that contingencies cannot be attributed to God, because God is the Necessary, and, while contingencies do result from the necessary structure of the natural order, this is distinct from the contingent, which is not addressed in the terms of eternalism or sempiternalism, such as necessity or destiny, but by those of presentism, such as free will and fortune. So, while God is ultimately responsible for everything, God is not responsible for them as God, the Whole, Natura naturans, but as humans, parts, Natura naturata. The way that eternal God relates to temporal humanity across this philosophical division is through voluntary progress to the Good, through which we experience happiness and know God as our destiny. Euclides, a Parmenidean, regarded the opposite of the Good as non-existence. As Plotinus reminds us, too, evil is a falsity or negation, and, as such, has no absolute referent to speak of, being a privation of being, for falsity or the negative is of that which is not, and that which is not has no being. Similarly, darkness is understood to be a privation of light, as Isaac Newton showed us.

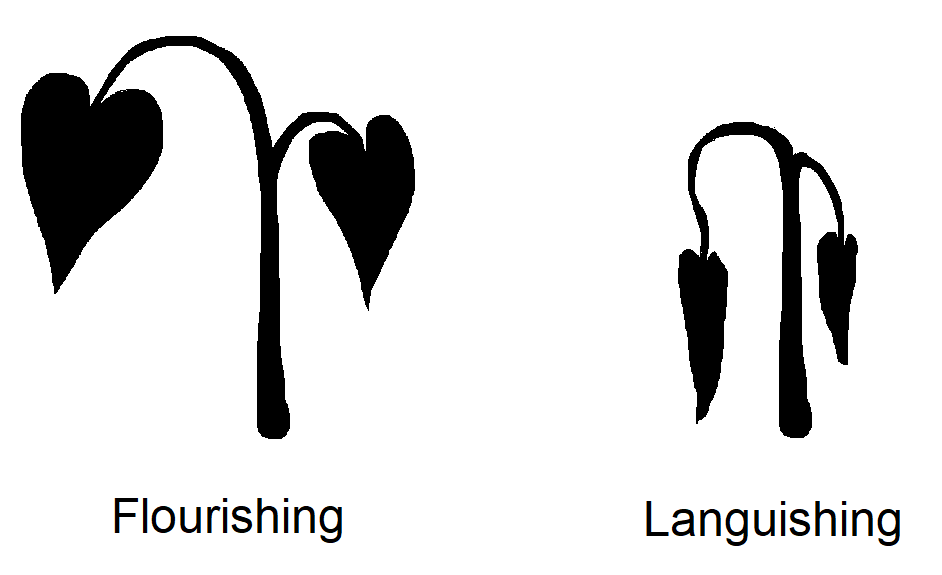

Temporally speaking, when a living thing has its needs met, its wellbeing, or health and happiness, can become objectively knowable in the form of its flourishing, its outward signs of prosperity—which Aristotleans and Stoics know as eudaemonia—, while that which does not have its needs met will suffer from languish, its outward signs of misery. If one properly nurtures a plant, for instance, by providing it access to adequate sunlight, watering it appropriately, and giving it proper nutriment, the plant w ill grow to live out its natural lifecycle and, if possible, will reproduce itself. In this, the plant’s wellbeing is obvious from its flourishing, which requires no communication of sentiment from the plant for verification, no relay of subjective data. On the other hand, if a plant goes neglected, and does not receive the appropriate amount of sunlight, water, and nutriment, it will begin to wilt, wither, and shrivel, and in this its languishing can be discerned without having to be told of its subjective anguish, if indeed it experiences it. This is not arbitrary, but is the case in every instance. Too much or too little of what a living thing needs results in its languishing. This is the natural order of the Universe, and it applies not only to plants, but also to animals and humans. Charles Darwin catalogued the emotions of animals and humans as they are physically expressed, perhaps being the first to do so with photographs, pointing to the objectivity, even if imperfect, in discerning others’ emotional states. Mental associations, or corollary experiences, of good and wellbeing, combined with introspection and empathy, allow us to correlate, with some degree of certainty, objective wellbeing with subjective happiness. So, when something is flourishing, there is a strong likelihood that it is also satisfied, or happy.

ill grow to live out its natural lifecycle and, if possible, will reproduce itself. In this, the plant’s wellbeing is obvious from its flourishing, which requires no communication of sentiment from the plant for verification, no relay of subjective data. On the other hand, if a plant goes neglected, and does not receive the appropriate amount of sunlight, water, and nutriment, it will begin to wilt, wither, and shrivel, and in this its languishing can be discerned without having to be told of its subjective anguish, if indeed it experiences it. This is not arbitrary, but is the case in every instance. Too much or too little of what a living thing needs results in its languishing. This is the natural order of the Universe, and it applies not only to plants, but also to animals and humans. Charles Darwin catalogued the emotions of animals and humans as they are physically expressed, perhaps being the first to do so with photographs, pointing to the objectivity, even if imperfect, in discerning others’ emotional states. Mental associations, or corollary experiences, of good and wellbeing, combined with introspection and empathy, allow us to correlate, with some degree of certainty, objective wellbeing with subjective happiness. So, when something is flourishing, there is a strong likelihood that it is also satisfied, or happy.

When individuals engage thoughtfully in purposeful, end-directed action, they exemplify syntropy within the Monad, and temporally and phenomenally participate in the formation of order, fostering the emergence of coherence and organization within the Universe. Purpose, bestowed upon us by God’s necessity from within us, is responsible for human nature, our inherent instincts, tendencies, inclinations, orientations, and desires. God made humanity concerned with its own benefit, but individually imperfect and interdependent, as John Toland and Matthew Tindal attest in echoing Spinoza and Bruno, such that they will have to pursue mutual benefits. As such, there is no offense to God in pursuing one’s own self-interest. However, if such a pursuit is short-sighted, God will probably, temporally speaking, and certainly, in the ultimate and in aggregate, rule in favor of one’s fate. There is never an offense to God, because neglect of God results instead in the suffering of the individual, not in harm to God, who cannot suffer harm imposed by mortal beings. As such, the drive for self-preservation reflects aspects of the natural order, and such drives lead us to do things like forming loving relationships, pursuing knowledge, and behaving well. The natural human impulse for self-preservation, an inclination for striving, or conatus, as Spinoza would say, is an inner demand to keep going on with existence and to improve both oneself and one’s surroundings such that one can expect one’s wellbeing to be secured and one’s worldline to be extended.

Human wellbeing is dependent— as Herbert Spencer told us, echoing Aristotle— upon the constitution of and the conditions experienced by the individual’s faculties, or capacities. All pleasurable sensations are cognized through the inner senses of the individual, for instance, as it regards the surroundings in which the individual is immersed. And many pleasant surroundings—for instance, one’s home— are derived from the capacities of the individual. Wellbeing is found in a compatibility between one’s constitution and one’s conditions, and is coextensive with success. Where there is not a match between one’s constitution and one’s conditions, suffering occurs. Where the fish finds itself without water, for instance, or where the bachelor and widower find themselves without wives, where the independent mind is compelled to learn what is not of interest to it, or where there is a hand on a hot stove, there is suffering, and only a lesser wellbeing than might otherwise have been attainable. But suffering is limited by progress, which, in aggregate, replaces suffering with wellbeing. The child learns not to touch the stove and warns his or her friends, independent minds contribute to revolutions, and bachelors and widowers marry and remarry and either succeed or fail in duplicating themselves to face sexual selection once more. This process entails that those who fall behind in progress cease to be, either themselves or as a genetic lineage, making room for those who are better-suited to exist in that point in space and time those who have failed have left vacant. Herbert Spencer’s name for this was the Survival of the Fittest, a principle derived from the application of the Law of Supply and Demand to moral life. That which succeeds, continues, and that which fails, ceases. As a corollary, we may say that that which is good and right succeeds, while that which is bad and wrong fails, for failure is never good nor can it be done right, and success is not wrongly achieved or aspiring to do bad. And so it is, that that which succeeds is good and right for the duration of its success, while that which fails is bad and wrong. One who lives a successful life, syntropically claiming one’s destiny, flourishes, or thrives, while one who fails languishes, or pines, diminishing or deteriorating in their entropic fate, having their worldline cut short. There is nothing any human, stuck in their contingent, local, and temporal nature, can do to stop this, for it is a natural law.

Thankfully, the general wellbeing of humanity is an innate and providential requirement of Necessity. The Anthropic Principle, for example, first described by Robert Dicke, posits that the Universe is “finely tuned” by way of the natural order and its natural laws to emerge life and intelligence capable of purposeful action, as can be told by the fact that any observation of the Universe entails a Universe suited to observers and the evolution of life. This fine-tuning is demonstrative of the Watchmaker Analogy, of William Paley, which suggests that when one finds a rock one thinks little of it, but that when one finds a watch one demands that it could not have been an accident, but extends this logic to the entire Universe, arguing, in terms of some of the more recent intelligent design enthusiasts, such as Charles Thaxton, Michael Behe, and Stephen Meyer, that there is an “irreducible complexity,” to living organisms especially, but also to the cosmos at-large. As Herbert Spencer may have been first to point out, atoms combine into molecules, and molecules into singular cells that form tissues that form organs that form multicellular organisms, which themselves band together to form societies. This being so, we are, in part, the collective will of our cells, and our collective will has a similar relationship to society, all of this being an expression of the innate tendency of the Universe to intelligently create us and our societies.

Certainly, morality is necessary to the maintenance of human wellbeing, and it cannot come into conflict with the physics of the Universe. Human flourishing necessitates certain moral and ethical actions that contribute to the realization of human potential and collective well-being. As such, there exists a harmonious relationship between the physical and moral aspects of the Universe, allowing for the emergence of conscious beings within it who are capable of reflecting on their place within it. Since God wills that humanity shall have wellbeing, and since also human wellbeing is dependent upon the exercise of human faculties and capacities in achieving its purpose, suggests Spencer, it follows that God wills that humanity uses its faculties and capacities for its wellbeing. Humans have the faculties or capacities to contribute to the flourishing of life so that they can do so, that is, and so are obligated by Nature to do so. Thus, individuals are motivated to act in ways that align with their inherent capacities and contribute to the flourishing of life.

Morality and ethics— topics of interest since the time of the ancient poets, such as Homer and Hesiod, and the prophets, such as Zoroaster and Moses, and wise statesmen such as Hammurabi and Ptahhotep— differ, though they are often used interchangeably, such that the rhetorical difference is a matter of convention. Morality is often understood as the subjective and personal discernment of good or bad ends, often as those ends regard the actor’s wellbing. It is largely rooted in emotions and feelings, as applied through our conscience to the cognition. It also forms the basis upon which we judge and construct the ethics of right and wrong actions, as understood externally as sensibilities, those public sensitivities to others’ feelings, as was understood by Samuel Johnson, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Adam Smith, and Immanuel Kant. Ethics provide an objective and interpersonal framework for inductively evaluating actions as right or wrong and establishing societal norms, reflecting what is witnessed to be sensible within a given society, especially as it regards others. Ethics guide moral behavior towards those ends that members of society have been brave enough to express as moral sentiments to others (and thereby contributing to norms of sensibility), and which have been witnessed and emulated or approved of by a critical mass capable of normalizing them. Ethics, then, is about right and wrong, correctness and error, which is objective and inductive, and it is applied to others in interpersonal relationships as witnessed from outside; while morality is about good and bad, pleasure and displeasure, which is subjective and deductive, as it applies to one’s self and one’s personal interests according to one’s own conscience. The causal chain to this, then, is that morality is expressed as sentiments, which establish sensibilities, and ethics is about the principles most conducive to sensibility, and so which best serves the aggregate public expression of individual morality, excepting only for the superior conscientiousness of individuals capable of persuading toward a new sensibility. Preservation of others can be motivated by self-preservation if those others are of monumental value, such as a beloved pet or a good family member or friend, or an important leader or founder.

Morality and ethics often approximate the natural laws in the form of moral and ethical principles, descriptions of ideal outcomes, and consequences of the ignorance of natural laws for deviating from the ideal, typically serving a use in purposive, normative human endeavors. While a true law cannot be broken, and though principles can describe laws more properly, principles can also describe the operations of the natural laws in terms of the way they are generally expected to play out with human action. Whereas Newton’s law of gravity, for instance— that the centers of mass of objects attract one another—, is always in effect, principles can also involve should statements, statements about the best actions for attaining the desired results. Unlike true laws, which are rooted in sempiternity, and cannot be deviated from or broken, principles which are not themselves laws may describe what will happen with attempts at adherence to or deviation from the law, and, as such, are contingent, and a part of temporal existence. Those things that one should do adhere to the law, and as a consequence contribute to flourishing, and so are moral and ethical. However, flourishing is not an inevitability, because there are times when individuals act without Reason and do not do what they should do, and, so, instead succumb to entropy. Collective wellbeing, on the other hand, arises from the rational recognition of what is generally syntropic, for, sempiternally speaking, it is syntropy that is objectively conducive to human flourishing and the realization of humanity’s true nature as part of the divine substance. As such, what is conducive or harmful for flourishing, what contributes to human syntropy, is what constitutes good or bad and right or wrong, socially-speaking, and this includes our sensibilities towards animals and even plants, as well.

Morality and ethics are often expressed in terms of values. Values refer to those things that we see as being of some importance to our wellbeing, that we see as being good, or satisfactory. Most of our values are healthy and wholesome, but there are some values that are not. For instance, some people value things such as recreational drugs, LGBTQABDSM, man-made religion, exploiting others, ritualistic abuse, and so on. Such values, of course, are vicious, or imbalanced, rather than virtuous, or “excellent.” Excellence must be maintained through good habits, or beneficial routines that have become second-nature. Vicious values are those that do not do this, but instead function according to whims and hysterias. Virtuous values are those that align to principles, as established through good habits. For instance, diligence, meaning being responsible, thorough, and careful— also related to forethought, thinking ahead, and prudence, or acting with good reason—, is a moral and ethical value based upon principle. Diligence has been expressed in such phrases as “the early bird gets the worm,” for instance, suggesting that those who plan ahead tend to fare better than others. Integrity, too, meaning to be earnest and honest, and well-founded as well as dependable, is a moral and ethical value based upon principle, as is the related fortitude, or strength, perseverence, or lasting power, and thrift or frugality, the good management of resources such that one earns and saves more than one spends.[8] These kinds of values are concise statements of traditional wisdom, that hermeneutic knowledge that captures the lessons of the ages, to be relayed to future generations. Other great moral and ethical values are conscientiousness, being much like diligence but applied to moral and ethical standards, and moderation, keeping from both excess and deficiency. The list goes on, including values such as amicabilitity, conviviality, politeness, and etc. This all being the case, and through observation and reflection upon Nature, an understanding of certain temporal principles and sempiternal laws, accessible to rational beings through Reason, and correctly valued, can guide one’s moral and ethical behavior to do good and right, so as to succeed, as Aristotle makes clear.

Individuals who become aware of and value principles are naturally inclined to align their actions with them. This alignment is not arbitrary but is rooted in the teleological structure of the Universe, and individuals who become aware of their purpose are guided by inherent tendencies and inclinations that align with this structure. The Universe, that is, is not indifferent to moral considerations, but instead conspires on behalf of the moral to assist them in achieving their purpose and realizing their objectives within the natural order. Those who become temporally aware of their sempiternal purposes are destined to achieve them for eternity. The proper feelings of reverence toward Existence, then, may be described as an awe for the mystical mundane, or preternatural, for the spiritually-imbued ordinary and the mysteriously familiar, and is accompanied by a rational-magical felicity and vibrant conviviality that adores life and living. There is no such thing as that which is truly supernatural, outside the bounds of Nature, for such would be beyond the realm of all-powerful God, but when we look closely at Nature we find that Zhe is quite miraculous in Zher essence.

Conversely, those who are not aware of their purpose do not have their own, and are fated not to achieve their own, but become the stuff to another’s purpose, as described by Hermes Trismegistus and Aristotle. They lack the understanding to align their actions to the Will of Nature, and so, in attempting to contradict it, find limitations and failure, falling folly to vice, and sometimes being enslaved or ceasing to exist as a result. The realization of natural impulses is not guaranteed, as individuals are vulnerable to hindrance due variously to their capacities and conditions. Ignorance or lack of understanding, irrational reasoning, and distorted perceptions can hinder people from fully satisfying a richer purpose, as can lack of information, distractions, and so on.[9] To act reasonably or rationally, on the other hand, is to act virtuously, or in balance— without having an excessiveness or deficiency to one’s account, but instead being in equilibrium—, and with a clear purpose. Those who do not do this are inclined to atheism, or, worse, to anti-theism, misotheism, or even Satanism, and to depraved worldviews such as the aforementioned pessimism, nihilism, and absurdism.

Self-betterment, the improvement of one’s character, or moral fiber, allows individuals to partake in the ameliorative or melioristic changes that are inherent to God’s design, which have been described phenomenally as co-operation in God’s creative process or as a medium through which this sempiternal process occurs. Herbert Spencer suggested that such acts of self-betterment were necessary for keeping up with the aggregate self-betterment that one’s own combines with others to create, and which establishes ever-higher standards of conduct and a competition to meet these standards. This is, of course, the sempiternal attribute of syntropy directing the change in human lives. Those who do not partake in this process of self-evolution, suggests Spencer, are left behind to perish. But this naturally drives an increasing intensity of moral and ethical conduct, he says, which not only betters the individual in the constitution of their faculties, but also betters the social condition altogether. Such a process is responsible for the evolution from out of the savagery and barbarism, described by the Ancient Greeks and Romans and later by Edward Burnett Tylor, and toward civilization, the condition of society in which people behave civilly, or amicably, with one another.

God gave humans Reason, with which it can come to learn the natural laws, since, as God has given humanity laws to follow, Zhe must have also given it the means to know those laws, lest they not be put to proper use and cease to be affirmed as they now are. Indeed, Nicholas of Cusa affirms that knowing God is something like Archimedes’s example of the circle and the polygon, such that the more angles that are added to the polygon—a metaphor for the more one knows of God— the closer one approximates, even if never perfectly reaching, an understanding of God, and that the more we do this the better lives we lead. Natural law encourages introspection and self-reflection upon the ways that we wish to be treated, which naturally results in the expression of the Golden Rule, perennial wisdom popularized by Hillel and Jesus, that we should do unto others as we would have done unto ourselves, so as to avoid causing pain and to pursue increasing pleasure to others. This is especially beneficial when it is ethically reciprocated, and indeed a part of the motivation for behaving in such a manner may be in the pursuit of normalizing it, such that it may be more readily reciprocated, and such that the Golden Rule is sometimes identified with a wider Principle of Reciprocity. In this way, the Principle of Reciprocity, that when one takes one should give, and vice versa, arises from the inherent capacity to seek mutual benefit, and from the empathic trust that others, too, may have the very same capacity for introspection and self-reflection, allowing them, too, to act with rational self-interest. From out of the foundation of reciprocity can be established justice, which dictates that individuals should be treated with fairness with regard to proportionality and equivalence. Actions that promote fairness and reciprocity are universally, even if not absolutely, recognized as good, though they find expression in different cultural or societal norms.

Natural law serves as an objective standard of conduct, its interpretation providing a normative convention of moral guidance and a comprehensive framework for ethical and moral decision-making. Conduct refers to the way that one goes about doing things, typically as used in a general sense, as opposed to the particulars of manners, as manners are particular instances of conduct. Examples of common good manners include such things as standing and sitting up straight instead of hunching, smiling and greeting others, saying “please” and “thank you,” holding doors for others to pass through, and shaking hands for various purposes. Such acts are also known as good etiquette. Someone who regularly exercises their manners or etiquette in line with good morals and right ethics can be said to be exemplars of good and right conduct.

Conduct may, in aggregate, come to establish various kinds and degrees of societal demands, or norms, as first described by William Graham Sumner. A norm is that which has become normal, or expected from daily life, such that people can reasonably begin to expect it to occur. These can be such things as folkways, which are common but not mandatory ways of doing things, customs or best practices, which are like folkways that have become more standardized and expected, and may resulting in humiliation for breach, sensibilities, as have been discussed, mores and taboos, which are even more strict, and result in shunning or ostracism for infringement, or even legalities, which may even allow for physical intervention. The default state of law is that of Jungle Law, or the Law of the Jungle, stated plainly as “might makes right.” In this default condition, anyone or anything that can overpower another is the expression of this law. Norms move us away from this default state, toward a condition of agreement in which “right makes might.”

Human beings’ striving for self-preservation and wellbeing, guided by Reason, of course, requires conditions of freedom in which the exercise of one’s faculties and capacities may go unimpeded, except as limited by the freedom of others, as Herbert Spencer makes clear in his principle, the Law of Equal Freedom. While absolute freedom, the freedom to murder, rape, and plunder, serves to reduce freedom overall, by taking freedom from the victim, maximum freedom, where freedoms do not contradict, can be found only in the conditions of equal freedom, where each has the same freedom as the other, as Spencer tells us. Since God wills human wellbeing, and since human wellbeing requires equal freedom, says Spencer, God has imbued humanity with the corresponding natural impulse to preserve its freedom in order that it may do God’s will of being free. God wills that humans be free so that they may freely adore and revere Zhim, having given them the capacities for freedom and reverence for this reason.

Stoic statesmen, such as Seneca the Younger and Cicero, acknowledged an equality in the nature of human beings, from which they derived that slavery was an externally forced condition, in opposition to Aristotle’s aristocratic notion of human nature, that some individuals are naturally superior, and so others fitting slaves to them due to their inferior nature. This Stoic sentiment was, perhaps, the first inkling toward natural rights. Natural rights, great minds such as Spinoza, John Locke, Thomas Paine, and Lysander Spooner have taught us, are natural facts of individuals’ capacities, desires, and actions, functioning within the causal framework of the natural order, and secured by it contingently and socially in morally-agreed upon principles. A natural right, as definitions would suggest, is that which is naturally correct, or is the case accurately described or prescribed, as righteousness is correctness. That is, it can be observed to naturally occur, or else to be desirable and enforceable as a should, however contingent and in principle. Individuals have, and society has, a natural right to do what can be achieved with inherent capacities and conditional limitations, the constraints of the Universe, but no more than that.

Natural rights arise from individuals’ successes, whether as earned or as secured by the judgments of others. For example, the right to life emerges from individuals’ own self-preservation. The natural right to life is not merely a passive entitlement but an active assertion of one’s capacity to navigate and survive in world, secured socially by popular adherence as principle, and a generally ensured success by society. Similarly, the right to liberty arises from individuals’ own self-determination, and is secured by society’s concern for flourishing. And the Universe supports the development of social structures that allow for the exercise of these rights. The rights and responsibilities that God or Nature has endowed us with are, Locke reminds us, inalienable. They cannot be alienated or subject to a lien. And their origin was independent from government and the state, being temporal and contingent. As we are reminded by Francisco Suarez, it is the people who created government from out of their own natures, not the other way around.

The expression of our rights and responsibilities establishes them, however contingently, as a positive fact of nature, both for the duration of their expression and as a sempiternal portion of Eternity. As such, our positive rights and responsibilities, established artificially as natural facts, are identical to our natural rights and responsibilities. However, the recognition of natural impulses does not guarantee their realization, as they may be vulnerable to hindrance or violation due to factors such as ignorance, leading individuals to make unprincipled decisions, and to falter to entropy. For example, someone who is unaware of the consequences of their actions may unintentionally cause harm to others due to their ignorance or neglect, despite their intentions. Moreover, irrational or distorted reasoning can cloud individuals’ judgment and lead them to prioritize short-term gratification over long-term well-being or to justify immoral actions through flawed reasoning.

Principles, unlike laws, which are proven, are postulates that can be forsaken, though consequences are likely to be felt. Having a right to do something does not mean that one does not have to face any consequences, but that no human effort shall be authorized to restrict one from doing as one pleases in the area of a right. Nature does have consequences, or outcomes, and they can be good or bad according to one’s behaviors. As such, rights come with responsibilities, requirements of best practice, and living a lawful life requires that one engage faithfully in truthseeking and free and critical thought. In the “Old Testament” of The Holy Bible there are repeated instances of God punishing the world for ignorant transgressions against natural law, which can be interpreted as natural consequences. The most famous of these is, of course, the story of Noah’s Flood, wherein the sinful world is drown, but there are also others, such as the story of Sodom and Gomorrah, where the decadent cities are destroyed by fire and brimstone, or that of the sacking of Jericho, wherein God authorizes that the inhabitants be slain. When such acts are not performed indirectly by God, by way of a human medium, such cataclysmic judgments are known as Acts of God.

Casuistry, meaning “case of conscience,” first described by Aristotle, entails that one extrapolate principles from out of one’s prior knowledge, as judged against the conscience, to be applied in ruling on a current circumstance. If the primary drive of self-preservation is understood as fundamental to human flourishing, people may casuistically derive secondary principles such as the duty to refrain from harming others or the duty to respect the autonomy of individuals, and this then becomes a legal right. Legality is the ongoing, casuistic interpretation of law as already-defined in Nature and revealed through nature as we traverse through time. This provides opportunities to individuals to make use of collective reasoning that has come about through periodical happenings and recognitions of the working of God or Nature. Casuistic legality[10] suggests that humans may make judgments according to observational data and interpretations may set precedents, but also that new precedents or dictates may be established by those brave and conscientious enough to “push the envelope” by challenging the legality and going beyond its normal limits to establish something better, a new precedent or judgment. Our natural rights and responsibilities, as such, provide the foundation for common or case law, that contingent “law”[11] which arises according to codified customs and precedents or judgments of particular instances of offense. Such cases represent mortal, human interpretations of natural law and the natural order, and, as such, the laws that apply to them are naturally limited to the level of current human understanding. For this reason, it is best to speak of human “laws” as legalities rather than laws, as human “laws” are contingent conventions, being breakable and changeable. Aristotle believed in epikeia, or reasonableness in the application of justice, that a legality can be broken in order to achieve a Greater Good, such as by righting a wrong without causing undue harm in the process. It is the source of equity law, law centered around evenhandedness, and is commonly understood as a form of particular application of the law to a given case or as a gentler interpretation of the law, made according to circumstance.[12]

Constitutional and statutory “laws,” too, are established as interpretations of Nature. But whereas case law exclusively addresses matters a posteriori, or after-the-fact, constitutions and statutes often address matters a priori, providing solutions to foreseen problems. These laws, too, are contingent and conventional as well, though they tend to be of a higher level and so to experience a greater longevity. These legalities have been a major topic in social contract theory, theories about assumed “contractual” obligations associated with state rule, a sort of pseudomutuality, abuse under the guise of mutuality. For instance, Thomas Hobbes believed that a human’s natural liberties consisted of those things a human could do in conditions without intervention from other humans, such as to have a will to use one’s power as one pleases, and that this made for conditions that were unfit for the security of a well-lived life, a “war of all against all” wherein even the bodies of others can be claimed under one’s natural liberty. As he saw things, then, dominion had to be established by the state, defined by Max Weber as a monopoly on the legitimate use of violence, so as to allow for a more secure mode of living, and so as to compel people to do what is right, which is non-existent until enforced by a sovereign. Baruch Spinoza, as a consequence, held that natural rights were no different than natural capacities, and that individuals have a right to establish whatever governance that they can successfully initiate into being. John Locke, contrary to Hobbes, held that there were three fundamental natural rights, and that these included the right to life, liberty, and property, which were disrupted by a “state of war,” which he separated from a “state of nature,” which was non-Hobbesian. Natural rights, suggests Locke, arose from the recognized impulse of self-preservation. Locke understood humans to submit to “civil” government and legalities in order to evade the state of war, and to reinforce the original state of nature, which, contrary to Hobbes, Locke understood to be a condition of general equality and freedom. Thomas Paine went even further, and held that rights cannot be granted or revoked by human institutions, but that governments were produced for the purpose of protecting rights that already existed, and in this he was in agreement with Benjamin Franklin and followed by Thomas Jefferson. Those who do not adhere to the legalities of a society, whether rational or bogus, are known as criminals, or as outlaws if they fall outside of the protection of the law.

Legal rights arise as abstract principles, derived casuistically through practical reasoning— the use of one’s rational faculties and common sense to discern moral truths from primary precepts, and to thereby derive secondary principles of how to behave, again described by Aristotle—, from out of natural impulses ideally including conscientiousness, in order to collectively guarantee their realization (whether through reconciliation of past wrongs or as forbidden behaviors) as natural rights, rights that exist, sometimes erroneously differentiated as positive rights, rights that exist solely owing to human enforcement (as if separate from Nature or teleological forces). These performative and hopeful legal rights— more demands than obligatory facts of Nature—, such as the rights to the security of life, liberty, and property, are extensions of natural human impulses to defend these things and the capacities as collectivities to agree to realize them as an application of justice, fairness, and the protection of individual freedoms. The legal right to liberty, that is, becomes meaningful through cohesive agreement as to the essence and worthiness of the natural impulse, which is then used to preempt and retard certain undesirable outcomes, most notably losses from aggressions. Practical reasoning, as such, plays a crucial role in casuistically applying universal principles to concrete situations. Practical reasoning must consider if failures and faults are intrinsic, owing to the constitution of the individual, or extrinsic, being due to the conditions the individual is facing, such that the attempt might be seen as contingently noble, particularly as a novelty, something new. As such, when an individual is on trial, the society must also be put to trial.

Practical reasoning, as such, leads to the establishment of the reasonable individual. The reasonable individual, perhaps first rendered as such by Richard Hooker, is itself a concept defined by the moral sentiments and the far less-manipulable conscientiousness of the judge or jury. The “reasonable individual” represents an archetypical or idealized moral agent, one who exercises sound judgment. Evil, bad, or wrong behaviors are not expected to find success, and so are unreasonable behaviors. A reasonable human being is, by nature, one who casuistically submits a priori to observed outcomes of natural law such that the harms of contradicting it must not be further felt a posteriori, and who is decided by others to naturally find success from their actions, typically as a matter of moral consequence. Judges and juries naturally maintain the capacity to redefine a reasonable individual according to their own understanding of evil, bad, or wrong behavior. Further, some follow Adolphe Quetelet in setting the standard of the reasonable individual at the level of the average behavior to be expected from a human being. Whatever the case, the reasonable individual serves as a moral compass and standard for society, guiding individuals towards ethical conduct and harmonious coexistence. The reasonable individual, as a standard of human behavior, embodies to whatever extent agreed the ideals of sound and cogent judgment.

Central to a strong concept of the reasonable individual is the notion of Logos, symbolizing Divine Wisdom and Cosmic Order made accessible through Reason. Heraclitus gave us the concept of Logos, suggesting that it was the Reason or Truth that allowed the natural order to be translated into rational discourse, and which, itself, held the world together and demonstrated its oneness. Christians know it also, following the Gospels and early leaders such as Origen, as the Word. Throughout temporal existence there is a chain of success that can be witnessed from out of those who become aware of their purpose and of natural law, producing the perennial. The perennial is that which returns season after season, and in the cosmic sense refers to the reappearance, time and time again, of success originating from Reason. That which is perennial, that is, may be understood to be adhering closely to the Logos. Despite their divergent cultural and religious contexts, Jesus and Lucifer (including Lugh and Fri) have both been revered as the embodiments Logos, representing the Reason that permeates all aspects of Creation, the guiding force that illuminates the path of understanding and enlightenment, leading individuals towards higher truths and spiritual fulfillment, or self-awareness of their telos.[13] Across diverse cultures and traditions, the archetypes of the Sun and of the Morning Star speak to humanity’s innate yearning for spiritual awakening and transcendental truth. Individuals, driven by the quest for spiritual growth and alignment with Logos, are compelled to act in ways that contribute to the flourishing of life and the advancement of universal harmony.[14] Those who align with Logos embody a sense of moral clarity and righteousness, transcending the limitations of mere mortals.

Heraclitus held that one’s character is one’s destiny or fate. Unlike others who may be adrift in the currents of existence, the reasonable individual is one of superior character, and is driven by an inherent purpose, that of fulfilling his or her destiny and of the advancement of humanity. This awareness of purpose empowers him or her to pursue his or her goals with determination and clarity, and to leverage his or her knowledge of physical and psychical laws to navigate the complexities of life for his or her wellbeing and that of others. The reasonable individual exercises Reason in sense-making and discernment and aligns his or her actions with the dictates of natural law, ensuring harmony, justice, and equilibrium within society as it exists also in the cosmos. This serves as a beacon for others, inspiring emulation and fostering collective well-being.

Prestige, the regard of others, is the least obtainable of items, and, as such, is of the highest worth. One’s prestige is contingent upon the esteem and credit of others, including as it results in one’s reputation. This prestige cannot be gotten, except by winning over the hearts and minds of others in one’s favor, such as through magnanimity, being “big-souled,” which Aristotle names as the chief of virtues and associates with pride. While benevolence is doing good, or having goodwill, the highest of the moral virtues, and proficiency is doing right, or being capable, the highest of the mechanical virtues, the magnanimity of the superior individual is the marriage of benevolence and proficiency, and so constitutes the utmost high of the aggregated virtues. The magnanimous does what is good and what is right, and readily finds success in his or her favor. While falsity can be utilized to gain such a following, such as by convincing it, with the forcing of unearned wealth, of one’s innate value—as occurs with celebrities and politicians—, and while censorship can hinder the magnanimous from gaining exposure, there is nothing that can hinder the true magnanimity of the superior individual from gaining its proper due from all who are exposed to it, for magnanimity is a providentially self-evident fact, and the natural basis of prestige, a basis which unearned wealth may signify, but of which it is itself empty, a fact discoverable to the reasonable individual and capable of shedding light on the lie.

The magnanimous individual’s capacities allow him or her to aspire towards higher ideals and to make sound decisions and judiciously assess risks and opportunities, allowing for transcendence. By harmonizing his or her actions with the principles of syntropy, he or she contributes to the advancement of human thriving, and in his or her unwavering commitment to universal principles of justice, he or she cultivates trust, respect, and admiration among his or her peers, establishing him- or herself as an exemplar of virtuous conduct. This respect and admiration translates into confidence as well as social opportunities, granting him or her access to networks that further enhance his or her success and influence, and sometimes positions of leadership and influence within his or her communities and organizations. His or her ability to inspire trust and mobilize collective action toward common goals fosters progress and prosperity for all stakeholders involved. As such, his or her moral and ethical superiority becomes a source of power, enabling him or her to effect positive change and shape the course of events in alignment with his or her purpose. The magnanimous individual, as a standard of superior qualities, then, serves as a benchmark against which individuals judge and measure the value of others.

The concept of the reasonable individual as a standard of excellence encourages individuals to engage in self-reflection and introspection, examining their own beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors in light of societal expectations and aspirations. By upholding the standards set by the magnanimity of the reasonable individual, individuals are socially incentivized to cultivate and exhibit virtues that contribute to individual and collective well-being, fostering a culture of excellence. By celebrating and rewarding individuals who embody virtues, and encouraging their emulation by others, societies create incentives for the cultivation of these qualities, leading to the gradual improvement of moral and ethical standards across generations. In this way, the construct of the reasonable individual serves as a mechanism for social evolution and progress, driving the continuous refinement and enhancement of human societies, ultimately leading to the improvement of the species as a whole. As such, the elevation of the magnanimous as a standard of excellence and as a societal ideal represents an act of collective, conscious and self-directed evolution, reflecting a shared commitment to attend to human flourishing, and an intrinsic drive towards self-improvement.

Malice, on the other hand, is the inspiration to intentionally do detriment to others, and is the opposite of the benevolence of a reasonable individual. Combined with ineptitude, it composes the opposite of magnanimity, pusillanimity, lacking in righteousness. The malicious behaviors of “pussies,” that are harmful to the wellbeing of others, thereby limiting their thriving or flourishing, are naturally criminal, or mala in se, “malicious in itself,” in terms of the Roman understanding. Those behaviors that are not naturally criminal, but which come up against wrong precedents or against convention of statute, are not evil in themselves, but are mala prohibita, “malicious because forbidden by decree.” The natural distinction between mala in se crime and government is that of loser and winner in the competition over legitimate or accepted assertions of law over others, with the most successful belligerent claiming a monopoly on the legitimate use of violence and establishing government thereby, instituting legalities under the false color of law.

The Constitution of the United States of America, which had followed the Articles of Confederation, is a compromise between the governmental or state forces of Authority and the civil forces of Liberty, as is exemplified by the first act of the American Revolution having been the Boston Tea Party’s raid on the East India Company and its thirteen stripes of its flag having been anticipated by the flag of that very same Tea Company, as the debates between the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists (or True Federalists) also make clear, and as was described by Pierre Proudhon’s science of federalism. As such, Authority represents a cosmological Evil, or Strife that juries must decide against, while Liberty represents the cosmological Good, or Love, which will inevitably find enduring success, teleologically, eschatologically, and sociologically-speaking.

The people of the United States have a right, recognized and authorized by their country’s founding documents, and in particular The Declaration of Independence, to, if they so desire, and aided by their comprehension of natural laws that make such authorization redundant, abolish government through civil forces, including those of voluntary association and voluntary disassociation, the legitimacy of which is founded in the civility of their actions and the nature of government’s authorization, and is not limited from the use of violent defensive force. The people being the principal who— apparently!— authorized the governmental relationship in the first place—government being accepted by common law according to Blackstone’s writings on the laws of England—, the people retain forever the natural right to revoke their decision, originating from their inalienable conatus. As such, it is an error of Blackstone’s by standards of natural law, and so a natural absurdity, to provide a jury the right to contract on behalf of the rest of their countryfellows if those countryfellows do not intend to abide by the obligations established by the jury in the first place, as if the jury had the right not only to review offenses a posteriori but to legislate behaviors or to override the decisions of all future juries in its verdicts, a posteriori. And so the establishment of government by way of jury is itself contingently null and its claim dependent upon government’s control of the population in accord with that jury’s decision, that control resting upon founding myths, ideological indoctrination, psychological subversion, compulsory taxation, and economic favoritism. That the state is itself a product of natural right is not under question, but whether it can sustain its infringements in languishing the people, whether its natural right is also a perpetual one, is what receives the light here. It cannot. The state, too, is a mortal entity.