This Text Can Be Found in the Book,

The Evolution of Consent: Collected Essays (Vol. I)

Introduction

Two beautifully libertarian and populist philosophies, Georgism and mutualism, should not find themselves at such odds with one another, and, yet, they do.

In this treatise I will analyze the conflict between these two schools of thought, Georgism and mutualism, and show that these two groups, at the root of their philosophies, actually share a lot more in common, than different, from one another, and would gain largely from cooperating and adapting one another’s ideas. I will also be contributing a new model of returns, which will allow us (Georgists and mutualists) to better communicate our meanings with one another as it relates to issues regarding the returns and fairness of distribution. I will conclude with discussion regarding the social effects of geo-mutualism and its expression as a panarchy.

The Problem of Language

Many disagreements between people, in my opinion, are semantic in nature. This is because we form our beliefs based on the information we have received in the past, and inform our actions with these opinions. This is all natural and well, but semantic limits should be recognized in order to transcend our current paradigm, which has been built on these opinions and actions. The limits, of course, are tied to our inability to share experiences. This, of course, is changing, and, with the evolution of human capacity for the use of signs, we are becoming more and more capable of describing our experiences to one another. Communication is becoming, and, although we still get into arguments of a semantic nature, it is in these difficulties that we find the next modes of construction and innovation of language. It is our duty as human beings to create and use dialects in increasingly reconcilable ways, in order that language itself may be universalized. La Parole becomes La Langue.

There are a number of debates being held that, while signs of healthy desire for communication, often remain stuck on the surface, taking words to be intrinsic in meaning, rather than descriptions of a particular portion of reality. When the deeper meaning behind words are lost, so too are the intentions. Dog to one may mean Chihuahua, while to another it may be Doberman. A sign reading “Beware of Dog” has very different meaning when set beside these very different (but almost identical, genetically) animals; one is undoubtedly comical, while the other is quite serious. Likewise, there are homophones between languages, which carry very different connotations to their speakers. At times it is more important to try to get a grasp of the context of another’s signifier than to assume it applies to the same referent. That is, we must look to the intentions behind words, and not get caught up on the surface values.

Some commonly discussed, and misunderstood, signifiers we use in our speech and writing today are the words interest and rent, particularly as discussed in anarchist, libertarian capitalist, libertarian socialist, and Georgist circles. The purpose of this writing is to create a common dialect, by which these groups may better understand one another. I will especially be focusing on the area of economic returns to land, labor, and capital.

Though I hope to encourage more thought from the wider anarchist audience, this paper will focus more largely on the debate between Georgists (especially geo-libertarians and geo-anarchists) and mutualists than between any other groups. This is in assumption that most voluntaryists, agorists, panarchists, and others on (what I consider to be) the libertarian right can agree with the Georgist distinction of the three factors of production (land, labor, capital) and their returns (rent, wages, interest), while most libertarian communists, communitarians, collectivists, and more on (what I consider to be) the libertarian left can agree with the traditional mutualist use of these terms (I’ll be getting into the returns in a moment). Looking past the quarrel, I will demonstrate that most of the debate between Georgists and mutualists is semantic in nature, and that both tend to describe similar desires of outcome, while using different language. First, an introduction of each.

Mutualism

Mutualism is a political and economic philosophy that was developed during the mid-19th century by thinkers like Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and, to a lesser-extent, the individualist anarchist Josiah Warren. Mutualism is typically considered the original form of anarchism. Mutualists subscribe to the cost-principle, as established by Warren (and implied by Proudhon), and to the principles of shared-ownership and federation as provided by Proudhon, as well as occupancy-and-use standards of land tenure, and the approach of mutual credit banking, which was shared between them.

Mutualists believe that in an atmosphere of free mutual credit and usufruct land-titles that few, if any, would voluntarily sell their labor on the market for less than its fair rate, and would instead prefer to work in self- and cooperatively-owned and managed firms. Mutualists envision a banking system that offers credit to the populace at large without, or at minimal, interest, and believe that such a system would make land and capital abundant to all, eliminating the artificial bargaining power of employers, and allowing every worker to have the means to own their source of employment.

One of the core elements of mutualism, the cost-principle, can be stated as cost the limit of price. The mutualists believe that the fair limit to prices should be based on labor, or cost, because, as Adam Smith notes in Wealth of Nations, “The real price of everything, what everything really costs to the man who wants to acquire it, is the toil and trouble of acquiring it.”[i] Thus, mutualists hold to the labor-theory of value; although, a more subjectively-measured one than often thought.

Among prices that are considered outside of cost are taxes, which are clearly taken against the will of their victims, as well as rent, interest, and profit. These are all considered returns that are due not to labor, but to privileged property given by the state. Mutualists argue that without the state providing monopolies economic power, that profit, interest, and rent would completely or, at least, almost completely, disappear, that workers would largely own their own jobs and keep their returns without paying bosses, money would be lent into the economy without any interest going to bankers, and land would be freely occupied and used, without anyone having to pay rent to landlords.

Georgism

Georgism is a political and economic philosophy named after its founding thinker, Henry George. George was famous for his proposition that everyone had a right to the Earth, and that economic rent, or the surplus value of natural resources, is the most sensible thing to tax, as the Earth is not a product of human labor, but instead precedes it:

The equal right of all men to the use of land is as clear as their equal right to breathe the air — it is a right proclaimed by the fact of their existence. For we cannot suppose that some men have a right to be in this world, and others no right.[ii]

Statements such as the following led the Georgists to also be known as the Single-Taxers:

The tax upon land values is, therefore, the most just and equal of all taxes. It falls only upon those who receive from society a peculiar and valuable benefit, and upon them in proportion to the benefit they receive. It is the taking by the community, for the use of the community, of that value which is the creation of the community. It is the application of the common property to common uses. When all rent is taken by taxation for the needs of the community, then will the equality ordained by Nature be attained. No citizen will have an advantage over any other citizen save as is given by his industry, skill, and intelligence; and each will obtain what he fairly earns. Then, but not till then, will labor get its full reward, and capital its natural return. [iii]

The philosophy regarding a common claim to the Earth did not originate with George, but George was perhaps the largest popularizer. Before George, such thinkers as Baruch Spinoza, Thomas Paine, John Locke, Herbert Spencer, and many others also made arguments in favor of common or collective ownership of the Earth (although Spencer would later recant his ideas, causing George to write a strong criticism of Spencer in A Perplexed Philosopher).

Henry George proposed that the most just basis of taxes was the tax on land’s surplus, or economic rent, as such taxation would not rob the laborer of their product, but would allow them to retain their full return on their labor and capital. Georgists refer to returns on capital as economic interest, and on labor as economic wages. They argue that so long as these wages and interest are not interfered with, a tax on land would not interfere with the economic incentive to produce, like most other taxes do, and so would not cause scarcity and economic stagnation. Georgists also argue that such a system would still allocate the most productive land to the most productive workers, increasing productivity, in line with comparative advantage.

Though Henry George himself was a statist, and had heated written discussions with the individualist anarchist, Benjamin Tucker, not all Georgists are statists. Contemporaries such as Fred Foldvary have written favorably about the coexistence of anarchism and Georgism. Ralph Borsodi, before him, who was influenced later in life by the anarchist, Laurence Labadie, and the writings of Josiah Warren— although his manifesto espouses a localist, minarchist, decentralism rather than anarchism—, was influenced heavily by George, as well, and created the Community Land Trust movement, which is still promoted by his School of Living, and was promoted also by E.F. Schumacher.

Community Land Trusts are voluntary associations for the purpose of sharing the ownership of land, largely to protect the security of land for future generations, bring down the cost of rent, allocate surplus, and share in community life. Typically, the community places control of the land in a common trust, which usually operates on consensus or some sort of supermajority voting, and which leases the land to its members, usually for 99-year terms (yes, you can leave). According to many anti-state Georgists, a society that is both compatible with Georgism and anarchism would include many such institutions, which would provide protection and other agreeable services, and would distribute the rest of the collected rent as dividends to all involved parties, serving to equalize, and legitimize, property rights for all.

The Mutualist and Georgist Disconnect on Rent

Georgism and mutualism have historically been antagonistic to one another. This is largely due, in my opinion, to the fact that the two philosophies really have so much in common, but have such a hard time understanding one another. Both mutualism and Georgism are rooted in libertarian approaches to socialization, or at least to distributed wealth, but where mutualists focus first on socializing credit, Georgists focus on socializing land. Mutualism comes from a stronger historical tradition of (small-s) socialism than Georgism, and reflects this greatly in its aims of owner-operators, while Georgism comes from a largely capitalistic approach, generally being sympathetic toward employers, but bends to socialization of wealth in the area of land. This is partly because mutualism, as an organized movement, developed in France, where space was shared and collectivism was on the rise, and Georgism developed in the Americas, which had gone through a period as a frontiers society, with space giving promise to individualism. A hard line is not drawn because of the differing approaches to labor and management, however, as many Georgists favor cooperation in industry and free banking, and many individualist anarchists who have supported mutual banking have also argued in favor of employment as an organizing principle.

Taxation of rent provides one of the large debates between mutualists and Georgists. Getting into the classical factors of production (land, labor, capital) and their returns (rent, wages, interest), mutualists generally stray from the idea of paying “rent” to anyone, and Georgists propose rent be paid to the community by way of taxes. Mutualists and Georgists view the payment of rent in different ways. To the mutualist, rent is the return not to the tenant-landlord, but to the absentee-landlord, who is not using the property they are gaining from; rent entails payment for the use of property which the owner is not using. To the Georgist, rent can include wealth that never left the hands of another person, but which was gained by virtue of the land.

In rejecting the Georgist analysis of rent, I feel that mutualists are at fault. They would do much better to understand the argument of Georgists in regard to returns on land, and do away with the simplistic notion of rent simply as a transaction, rather than a return on land itself. In many ways, absentee-landlords are only enabled by title to economic rent to begin with, which allows them to rent their land to someone else, and use that rent to pay for another piece of land which may be less productive. They’re okay with this, because they probably don’t intend on producing there anyways, since they can subsist off of the efforts of others, by collecting the rent from their tenants who are using their productive land.

In my view, the contemporay mutualist position is short-sighted in regard to land, going against its own mission of internalizing costs. That is, economic rent distorts the cost-principle, because the wielder of economic rent can charge a price for their resources which is not due to incurring cost (effort, disutility) toward their trade-partner’s benefit. That is, they can gain someone else’s labor product in an exchange, even while they themselves have exhausted little or no effort on their end (and thus, have reduced zero costs for the consumer by way of labor, deserving no reward). To the Georgist, this return without effort is economic rent.

While today’ mutualists are against Georgist rent-sharing — the payment to society for use of land— on principle, Proudhon himself was actually in favor of such compensation. This can be seen in such statements as,

Let us suppose that an appropriated farm yields a gross income of ten thousand francs; and, as very seldom happens, that this farm cannot be divided. Let us suppose farther that, by economical calculation, the annual expenses of a family are three thousand francs: the possessor of this farm should be obliged to guard his reputation as a good father of a family, by paying to society three thousand francs,—less the total costs of cultivation, and the three thousand francs required for the maintenance of his family. This payment is not rent, it is an indemnity.[iv]

One can see by Proudhon’s words here that, though he may rail against rent, he believes something similar to George, though he calls the payment to society indemnity here, in opposition to rent.

Occupancy-and-Use

Occupancy and use must be given a deeper definition than the one commonly used by mutualists if it is to be considered a viable option. The current usage thrown around, taken too literally, has no practical application, has no standards of determining what constitutes such possession-usage. What if I step out for a bit? Is my land, my house, free to claim by squatters? Who has the right to occupancy-and-use, and when? It is my belief that this must be sorted out by contract, but in setting up contracts people look to what is most fair.

Typically, Georgists are seen as antagonists of occupancy-and-use standards of land tenure. Some Georgists do insist that conflict over land creates the necessity of a state, but others are increasingly fond of anarchist, or panarchist, approaches. Some geo-libertarians and geo-anarchists have indeed insisted that communities that voluntarily subscribe to a land-value dues (rather than tax), like Proudhon’s “indemnity,” will be able to outcompete communities that don’t. Fred Foldvary points out that,

In a libertarian or anarchist world, some people might be unaffiliated anarcho-capitalists, contracting with various firms for services. But if we look at markets today, we see instead contractual communities. We see condominiums, homeowner associations, cooperatives, and neighborhood associations. For temporary lodging, folks stay in hotels, and stores get lumped into shopping centers. Historically, human beings have preferred to live and work in communities.

He continues, saying that in anarchist geoism (Georgism),

Geoist communities would join together in leagues and associations to provide services that are more efficient on a large scale, such as defense, if needed. The voting and financing would be bottom up. The local communities would elect representatives, and provide finances, and would be able to secede when they felt association was no longer in their interest.

[…]

In the anarchist context, private communities and companies would provide the civic works and collect the payments by contract. Geoist communities would try to assess how much of the rental is natural rent, and distribute that equally to the population in those communities. Market anarchists outside the geoist leagues would probably be hostile to this rent-sharing system and might refuse to trade with the geoists, but that would not be much of a problem for geoists, since the efficiency of geoism would attract much of the enterprise.[v]

On a similar note, the geo-libertarian, Daniel Sullivan, says,

There are excellent reasons for libertarians to prefer the land trust route over the political route. Private communities can be built on explicit contracts (leases) with the citizens, can have internal democratic processes that are vastly superior to electoral democracy, can be far more flexible and free of state intervention, and can be downright profitable (even with trust investors pocketing a mere fraction of the rent). Most of all, dealing with investors is far more pleasant and self-affirming than dealing with politicians.[vi]

In circumstances such as these, it seems that there is no longer a need to have a riff between Georgists and mutualists about taxation. Geo-anarchism, depending on how it is applied, could be the very mechanism that mutualists are lacking when defining occupancy-and-use standards to land rights; if you’re paying your dues the land is clearly being occupied and used, and is protected as such by your geo-association, or land trust, even in your physical absence. So long as the Georgists can practice geo-anarchism, I see no reason to continue arguing about the method of land distribution.

A Plea for the Commons

Both geo-anarchists and mutualists seem opposed to land monopoly and state-ownership. Geo-mutualism may not be so unrealistic. Clarence Lee Swartz:

Mutualists believe that both of these forms of inequity [monopoly and state-ownership] may be avoided. They believe neither in giving absolute titles to the unqualified possession of land, nor in denying all titles whatsoever. They propose to recognize conditional titles to land, based on occupancy-and-use by the owner; and they engage to defend such titles against all comers, so long as the owner complies with those sole conditions of occupying and using the land of which he claims the ownership. Under these terms there can be no monopoly of land, and no one who desires land for occupancy-and-use may go landless. Since no vacant land may then be held out of use if anybody desires it, each person may, in the order of the priority of his selection and according to his requirements and occupation, have equality of opportunity in the selection of land.[vii]

Mutualists, like geo-libertarians, should favor not private (capitalism), nor collective (socialism) rights, but the higher synthesis of common rights to land. Capitalism is an instance of private rights, which are rights to absolute and perpetual control of land by an individual, even at the expense of the collective; land-monopoly as we frequently have today, and as promoted by Austrian-style economists. Socialism is an instance of collective rights, which are most often managed by a power-wielding state, while geo-libertarianism is an instance of common rights, [viii] which can be managed by the people themselves. Daniel Sullivan, on the matter of collective and common rights, notes that,

A parallel confusion exists between common property and collective property, and the classical liberal concept of common property has been all but obliterated. An open park perhaps comes closest to the idea of common property, for anyone has an equal right of access to the park. However, restrictions on what one may do in a park, to the degree that they are arbitrary, render the park a collective property.[ix]

The Nature of Rights

Clarence Lee Swartz, a proponent of occupancy-and-use, is careful to clarify that rights (such as those to property) are not something that can be assumed, but must be either asserted with force, or, in lieu or forfeiture of force, with mutual understanding and reciprocity of rights through contract:

Fundamentally and elementally, of course, there is only one right – the right of might.

To talk about “natural” rights and “inalienable” rights is to talk about something that does not exist. To speak of natural rights implies that there is an unquestioned or an indisputable right of some kind that is inherent in the individual when he is born. If that were really true, then the right of might could not operate against it. In order that the right of might could not so operate, the inherent or natural or inalienable right would have to be of such a nature that no force could overcome it. Merely to state the case in that way is sufficient to show the nonsense of the notion that there can be anything superior to the right of might; unless there is some metaphysical meaning attached to those three adjectives that is not fathomable by the finite mind.

The real truth of the matter is that, since there is no right superior to that of might, all other rights, of whatever nature, exist only by sufferance; in other words, by contract or agreement.[x]

I must say it’s rather ignorant of Clarence Lee Swartz (whom I consider one of my own dear and well respected teachers) to have such intelligent views regarding the nature of rights only later to downplay economic rent, and act as if it should not play a role in the formation of the contracts he is maintaining. He’d do much better to have followed after Proudhon. If rights are not natural or inalienable, it should not be assumed that someone has ownership rights of property simply for possession. A truly mutualist society, where people freely forgo violence in favor of cooperation, wouldn’t be one based on assumption of property rights, but on reciprocity of property rights; that is, property rights by contract, meaning rights to equal value. I don’t think any institution could provide a better system of such reciprocal possession of land, defining occupancy-and-use by giving it practical application, than a geo-libertarian one.

There is no reason for any anarchist— if rights are not assumed, but claimed— to respect another’s self-claimed title to economic rent. In fact, as Jeremy Weiland tells us,

we may find the answer to the problem of persistent wealth imbalances in human nature. Two aspects of that nature are greed and envy. Just as stockholders are always in danger of management and employees siphoning off profits and imperiling the long term viability of the business, rich individuals face similar uncertainties of theft and fraud. Because the lack of a State would force these costs to be internalized within the entity rather than externalized onto the public, it is highly likely that the costs of maintaining these outsized aggregations of wealth would begin to deplete it.

The balance of power between the rich and non-rich is key here. Direct plundering of wealth, though fraud or theft, threatens the rich in a crippling way. It raises their costs directly in proportion to their wealth, either through insurance costs, defense costs, or losses. They have to worry not just about outside threats, but also the threats posed by their servants, employees, and even their family members. Because the wealth is centralized around one individual or one management team, it is near impossible to find any fair way to distribute the responsibilities of stewardship without distributing the wealth itself. Having a lot of stuff becomes more trouble than it’s worth.

Then he starts to sound a bit like a geo-anarchist,

Meanwhile, less rich people economize on these costs by banding together with other modest individuals to either hire outside defense (socializing protection on their own, voluntary terms) or by personally organizing to defend property (via institutions such as militias). Because the ratio of person to wealth is relatively greater, there are more interested individuals wiling to play a role in defense and maintenance of property. It’s the distribution of the wealth over more people that necessarily makes that wealth easier to defend. And since everybody has basically the same amount of stuff, nobody has an interest in taking advantage of, nor stealing from, others.

In fact, normal human greed suggests that there will always be an element of society that wishes to steal and cheat others. What the wealthy offer criminals like this in an anarchy is easy targets, because big estates are harder to defend and so invite more opportunities for plunder. Not only that, but its far more likely that wealthy estates will be targeted because its easier to steal a million dollars from the bank, or a vault, than to rob a thousand or so common people. The larger the disparity in wealth, the more intensively the wealthy will be targeted by criminals.

On the other hand, normal people would necessarily be less likely to be targeted by the criminal, for a few reasons. First, since the ratio of human bodies to wealth in a modest community would be much greater, the deterrent effect would be insurmountable to all but the most stupid crooks. Second, the criminal elements in a modest community are more likely to share in the legitimate wealth of the economy, preventing them from preying on their neighbors. Since the economy is completely free, current mentalities about the reasons for criminal behavior are minimized because people see that by working hard they can actually get ahead.[xi]

Similarly, it is my belief that rights to property stem either from physical force, contract, or both, and that, in the context of a free market, an equilibrium can be found where forceful action balances property rights and bilateral contracts emerge to forgo force, which is detrimental to both sides, compared to agreed-upon standards. The healthiest equilibrium I can imagine would be facilitated by geo-communities, as a standard of occupancy-and-use. Anyone not part of a geo-community would face a possibility of plunder, thus forfeiting their own rights to property. As Max Stirner makes clear, “Whoever knows how to take, to defend, the thing, to him belongs property.”[xii]

Economic rent can more easily be sorted out by contract than by force, in a way that is beneficial for all participants. Conflict escalates, and is hardly ever beneficial. Dan Sullivan illustrates the simplicity of sorting out land by contract:

Consider three fair-minded people who have come to inhabit an island, where sustenance is derived from fishing and from a small coconut grove. As there are plenty of fish and plenty of fine places from which one can fish, no conflict, and, therefore, no rent, arises. However, as the coconut grove is small, and all three people have an interest in possessing it, it becomes a matter of dispute, which can be most equitably resolved by the utilization of rent.

They could, of course, divide the coconut grove in three, but if it is inefficient for each to tend a third of the grove, they might resolve the dispute as follows:

One might say, “If you give me exclusive access to the grove, I will give you four coconuts per week per week to divide between you.”

Another, who believes he is more talented at maintaining a coconut grove, offers five coconuts per week. Ultimately, the highest bidder gets the grove, and the other two get the rent. This rent is a natural rent, and is used to equitably resolve the clash of conflicting rights to land. Thus, the rent does not belong to “society,” but the individuals who have given up their rights to the land itself.[xiii]

If mutualists can define occupancy-and-use more deeply, to include geo-communities, I think we can be on the way to something exciting, but Georgists have to return the favor. If mutualists concede Georgists the community claim to economic rent, Georgists should concede that mutualists are correct about interest and profit, at least as they define them. Much of the disconnect between mutualists and other schools have been semantic, and if Georgists and mutualists can share a common language, we can get past this problem. Mutualists, when referring to interest and profit— like Georgists when referring to rent—, are referring to something completely different than when Georgists refer to interest and profit.

The Mutualist-Georgist Disconnect on Interest and Profit

An area of contention between mutualists and Georgists, nearly as strong as the issue of taxes and rent, is in regard to interest and profit. This, sadly, is much more semantic than realistic, as geo-libertarians, as well as mutualists, oppose state-regulation of industry, often including the area of banking. Most of the contention is due to the fact that mutualists have historically called the return above the natural rate of labor and capital—due to privilege—profit and interest, in line with cultural definitions, while Georgists refer to any return on capital as interest, and on labor as wages, with any return higher than expected being profit. In-so-doing, Georgists ignore half of the economic problem, at least in popular terminology, as it has been described since the beginnings of civilization and modern economies: Interest, especially usurious interest. Stephen Zarlenga says,

it can be questioned whether George was too easy in extending [his] “justification” [that interest is due to the fecundity inherent in the “power of nature”] to all forms of taking interest. Rather than his usual approach of carefully discerning between economic activities, in this case he lumped them together. For example the Scholastics carefully distinguished between different forms of earning interest, which were always permissible, and usury, which was not. In effect properly charging interest on some loans becomes a cover for improper loan sharking, for example as practiced today by credit card companies, or the IMF, to take an extreme case.[xiv]

Usury has been condemned by Christians, Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists, and more; and I’m not speaking about changes in recent years, I’m talking about early-on in civilization, when money was a newer phenomenon, and many exchanges still took place by way of barter and gift. Zarlenga says,

In all George’s works read for this study, the word usury came up only once. George’s avoiding the usury issue, in a morally based work, may have stemmed from his faith in freedom of trade; in this case emphasizing the freedom portion of his two part formula; and de-emphasizing the responsibility portion of it as regards the kind of lending activities that are permissible within a framework of justice.[xv]

Indeed, the nature and treatment of usury has been a controversial subject for a long time. Many reject the concept altogether, and often because those who accept the concept prescribe solutions which hinder freedom of trade. Hugh Barty-King, in The Worst Poverty: A History of Debt and Debtors, remarks that, in medieval society,

A person without the necessary ready money who wished to affect an air of solvency, if not wealth, could do so by acquiring temporary affluence by borrowing, not from the tradesmen who sold goods, but one who sold money. The retailer’s profit came from the mark-up with which he charged the price he had paid the wholesaler or producer. The trader in money made his living from the charge he made his customers for the temporary use of his money, a trade known as usury (usura in medieval Latin).

Anyone who volunteered to relieve another’s financial embarrassment, by handing over some of his money with which to pay the bill which had caused the embarrassment, and then had to wait longer than he had bargained for to get his money returned, could claim compensation for his temporary loss to the extent of ‘that which is in between’ (id quod interest). The phrase referred, in the words of the Oxford English Dictionary, to ‘the difference between the creditor’s position in consequence of the debtor’s laches (neglect to pay at once)* and the position which might have been reasonably anticipated as the direct consequence of the debtor’s fulfillment of his obligation.’ It was a principle which had harked back to Roman Law. The compensation which became to be known as interest (interesse) was permissible when it could be shown that such a loss had really arisen (damnum emergens). Later, loss of profit through inability to reinvest the money (lucrum sessans) [opportunity costs] was also recognized as giving a claim to interesse. The sum which could be requested as interest was a fixed one and specified in the contract; though in thirteenth-century England they substituted a percentage of the money which was reckoned periodically to correspond with the creditor’s loss.

In medieval England the two procedures were only sanctioned by tradition. However the Christian Church in England, which took its ideas from the Pope in Rome, held that whereas compensating someone who had lent money to another to bridge a temporary shortage of cash was permissible, charging for the use of money lent was not.

It was not just impermissible. The Christian Church’s body of rules and regulations on how a Christian should conduct himself, the Canon Law, ruled that usury was ‘a sin’.[xvi]

The usury argument has two prongs. Those who ignore the problem, in protection of freedom of exchange— though their concerns about freedom of trade are reasonable—, do a great disservice to its victims. Those who see the problem, and treat it with coercive systems of law, do just as much disservice to the community. Under these circumstances it only makes sense for the two sides to dispute one another. One ignores the problem, and the other treats the problem with a bigger problem (the state). Instead, it should be noticed there is a cause of usury, and this cause is monopolization of credit, not payment for opportunity costs of the lender. Usury is very much an issue. Thomas H Greco, Jr. contemporary author of mutual credit, writes that,

The word usury has become taboo in our culture, particularly in academic and financial circles. It is almost never mentioned in the media anymore. But if we are to remedy the obvious inequities in the economy and discover a sustainable way of life, it is vital that we reexamine this concept and understand its economic and social impact. We need to know how it affects people in their daily lives— their ability to meet basic needs, to provide for their families, to enjoy lives that fulfill their creative potential. Those who call themselves economists have, for the most part, been derelict in their duty to provide such analysis. The few who have ventured onto this path have been ignored, repressed, and even vilified.[xvii]

Indeed, the mutualists allowed for enough “interest” to cover the operational-costs of the bank, usually teetering around 1% or less. Mutualists, then, should be more careful in their wide-sweeping condemnation of interest, or should at least define their terms more thoroughly, because at times there seems contradiction, even if the intentions are clear (to me, anyway). Mutualists teeter in their language between condemning all interest, and condemning interest over cost. Still, there is effort; Clarence Lee Swartz makes a careful distinction between profits of privilege and profits of business or enterprise, before clarifying that through the rest of his book (in line with mutualist tradition) he will be exclusively referring to profits of privilege as profits:

The item, Profits of Business, includes that profit which comes from enterprise and efficiency in the management of business as well as that which results from the legal privileges and monopolies that individual business firms enjoy. We may call the first the Profit of Enterprise, and the second the Profit of Privilege, i.e. – the profits resulting from tariffs, franchises, and other special privileges.[xviii]

[…]

(Hereafter in this book the term “profit” refers only to the “profits of privilege,” and does not include any reward which goes to enterprise, to managerial ability, and to labor).[xix]

When mutualists are talking about profits and interest, they’re pointing out the returns from privilege, the same privilege that Henry George condemns, but, in all of his glory, lacks the wording to distinguish when he says,

But while wages of superintendence clearly enough include the income derived from such personal qualities as skill, tact, enterprise, organizing ability, inventive power, character, etc., to the profits we are speaking of there is another contributing element, which can only arbitrarily be classed with these— the element of monopoly.

When James I granted to his minion the exclusive privilege of making gold and silver thread, and prohibited, under severe penalties, every one else from making such thread, the income which Buckingham enjoyed in consequence did not arise from the interest upon the capital invested in the manufacture, nor from the skill, etc., of those who really conducted the operations, but from what he got from the king—viz., the exclusive privilege—in reality the power to levy a tax for his own purposes upon all the users of such thread. From a similar source comes a large part of the profits which are commonly confounded with the earnings of capital. [xx]

It is precisely this sort of tax which is passed down that mutualists refer to as profit and interest, and not the returns that exist from having capital, unless that capital is privileged. One could levy a fair shot to the mutualists, because of their lack of terminology to distinguish fair returns and unfair returns, but this same charge could be faced by the Georgists, who use the terminology of interest as a return on any capital and profit as any return larger than expected (which is not composed of rent, which is then considered “spurious”). The fact of the matter is that the two systems of terminology clash horribly, while at the same time the demands of the two schools of thought are very similar.

The Nature of Interest and Money

Clarence Swartz declares that “The bankers’ profits are the cause of all other profits, and the reduction of the bankers’ profits, through the abolition of interest, will by the same token decrease all other profits.”[xxi] At the same time, he admits that interest is further the result of state-protectionism. Such interest could very well be argued, then, to be the levying of taxation which George is discussing, as the state relies on taxation for its existence. Clarence Lee Swartz:

The reasons why banks are able to make such large profits are that the State permits only one basis of value for the issuance of money, namely gold; that it further usurps the exclusive right to issue money on this one basis and to lend this money to the banks at a small rate of interest against security which is largely furnished by the bank’s customers; that it prohibits the issuing and loaning of current notes (no matter how well secured) by anybody but a lawfully organized bank, with penalties ranging from fine to imprisonment. By the Federal law the fine takes the form of a ten per cent tax upon the notes circulated, which, of course, acts as a complete prohibition.

Thus is established the money and banking monopoly which, by eliminating competition, makes it possible for the financier to exact interest for lending, not his own capital, but merely a claim to capital which is secured by the borrower himself.[xxii]

Swartz wrote this just before the gold-basis was dropped, but his argument applies today. Instead of gold, however, the basis of money has shifted to all taxable goods in the economy. Unregistered, untaxed, goods and services, are not monetized by way of bank loan. Registered business is taxed and subject to interest upon using their credit, creating a scarcity of money.

Henry George certainly had his own criticism of privilege, which was not so different from the mutualists. The philosophies are so similar in their demands, at times, that their clash over language hurts. George was even involved in some mutualist currency schemes. Stephen Zarlenga, in “Henry George’s Concept of Money,” suggests that, alternative currency

systems can be traced back to Josiah Warren, the originator of the Labour Exchange idea, put into practice by Robert Owen in London in 1832 after a very tight money period. In fact, Henry George was associated with organizing a variant of such a system for Tom Johnson’s company in Johnstown.[xxiii]

He says that,

In a separate case, Michael Flursheim [“one of George’s earlier protégé’s who emigrated to New Zealand helping to raise the land question there and in Australia”[xxiv]] formed the Commercial Exchange Company in New Zealand in 1898, which created its own money form, substituting debts between member merchants for cash. They accepted script from one another which had been printed by the trustees. The trustees loaned out the scrip, based on the credit of the participants, with the interest going to cover administrative costs. [xxv]

Georgists typically fall into two camps: There are the traditional Georgists, who support a return to a government greenback of sorts, which is not necessarily backed by hard goods, and then there are the free-banking Georgists, who typically support full-reserve banking with hard-backing. George himself was a proponent of money in the first view, not as representing hard goods, but as representing government credit. He says,

The truth of the matter is that the power to issue money is a valuable privilege which, to secure the best circulating medium and to put all citizens on a footing of equality, ought to be retained by the general government, and to be permitted to no one else, either individual or corporation. The greenbackers, who have insisted that national bank notes should not be permitted, and that all money should be the direct issue of the government , are in the right. It is a pity that so many greenbackers permit themselves to be used by the silver men, instead of insisting on their own principles. If we want two millions of notes issued every month, let them be greenbacks, and let the two millions now expended in buying silver be saved.

Nothing can be clearer than that the silver notes now in circulation do not derive their value from the silver which is supposed to be corded up in the treasury to redeem them. For they circulate at one hundred cents on the dollar, whereas the silver that is supposed to be lying in the treasury vaults for their redemption is only seventy-two cents’ worth. They would circulate just as well as if there were no silver in the treasury, and we might as well sell that silver off or put it to some more sensible use than hoarding it—say, for the construction of long-distance telephone wires for the post office department. And what is true of silver is true of gold. It is the credit of the government that furnishes the real basis for our paper money, not any deposit in government vaults.[xxvi]

This sentiment is clearly contrary to that of the free-banking Georgists— some of the geo-libertarians, and especially the geo-anarchists— who would have government reduced to nil. It may, however, ring out as being somewhat true to the mutualist, who sees necessity in confederation of mutual banks; though the term government would strictly not apply. The mutualists and Georgists did not get along, however. Henry George criticizes the mutualist, Alfred B. Westrup, when he says,

In this issue of THE STANDARD we give place to a condensation of a long communication from Mr. Alfred B. Westrup, of what styles itself the “Mutual Bank Propaganda,” in reply to a criticism by Thomas G. Shearman upon a circular issued by that concern. As to the article itself it is hardly necessary to say much. Who would profit if everybody were allowed to issue money? Evidently the richer class, who could start banks and issue money, and the large employers of labor, who could in many cases force money on their employes.

He continues, citing examples of private currency:

Lee Merriwether, the active and efficient labor commissioner of Missouri who recently made an exposure of how the Mendotta mining company was working the “free money racket ” on its employes by paying them in checks, has recently investigated similar cases in the southern part of that state. Here are some samples: “Holloday has a store, and if his employes do not wish to purchase his goods they get no wages at all. One of his employes, an intelligent German, whose board shanty, although meagerly furnished, leaky and full of cracks and holes, was scrupulously neat and clean, stated to me that last August, on the so-called pay day, he went to Mr. Holloday and asked that the wages due him be paid in cash, as he wished to return to his old home in Michigan. ‘I was feeling very poorly,’ said this employe, ‘and told Mr. Holloday that I wanted to go back to my old home to die. Mr. Holloday said to me: ‘You can die here just us well as in Michigan. I can’ t give you anything except checks.’ The checks are only good at his store. The railroad won’t take them, so I cannot go. My lungs are weak. I want to go to Colorado, but do not see how I shall ever get there, as I am never paid in money.’ The wife of this man, who at the time I saw him looked weak and consumptive, told me that although $17.17 wages were due her husband, she could not got enough money to buy a pair of shoes. She talked simply, not complainingly, as though it were the usual and proper thing to be paid in pasteboard, as though Mr. Holloday, in refusing to give her husband his wages in money, merely refused a favor.

While one of my agents, Mr. C. N. Mitchell, ex-mayor of La Plata, Mo., was in the office of the lumber mills, an employe entered and asked for his wages. The cashier handed him a check. Mr. Mitchell heard the employe ask for money. The cashier refused. The employe said he wanted to leave town, that he was tired of working for pasteboard. The cashier coolly replied that he could walk out of town if he wanted to go, that he (the cashier) was authorized to pay only in checks. On another occasion when an employe who had just received a check for his wages asked for cash, the cashier refused, saying: ‘I have paid you your wages, but if you want me to buy that check, that is another thing. I will give you $4 for it.’ The amount of the check was $7.20. The postmaster of Williamsville buys checks from employes for seventy-five cents on the dollar. Sometimes all that the employe can obtain is fifty cents on the dollar.

I have a number of other statements of Holloday’s employes to the effect that they had applied for their wages on pay day, but were refused payment in cash and were compelled to accept checks on his store. One man says that he waited at the office until eleven o’clock at night to see Holloday and get his wages in money. During this time Mr. Holloday remained locked in his private office. At eleven o’clock the clerks forced the employe to leave in order to close the office. He went the three following days, but with no better success and was finally obliged to accept checks in lieu of lawful money of the United States.” If the free money people had their way Holloday’s pasteboard checks would be lawful money of the United States, and pretty much every large employer would constitute himself a bank and begin issuing this sort of money.[xxvii]

George is very right to fear free-banking under a classical system of property, where there lies a distinction in ownership between employers and employees. He sets up a strawman, however, when he challenges Westrup of this dynamic. Clearly, when Westrup argues against consumer cooperatives, in “Co-operation,” he sees no need for such fiddle as George accuses him, because he favors worker-ownership:

All who have means should never let it pass out of their control; instead of a cooperative store being started or contributed to by those who purchase, subscribing to its stock, in which case their means pass into the control of other parties, such store should be started and carried out by a few cooperators among themselves, as we propose, each furnishing the stock in the department which he manages. In this case if he makes any mistakes it is at his own cost, and he alone is the sufferer.[xxviii]

There’s no reason to follow Westrup’s logic that consumer-ownership is never necessary. The mutualists, Westrup himself, were all in favor of mutual banks, anyhow, which are banks whose policies are owned by the policy-users, similar to a modern credit union (but generally more democratic). They favored worker-cooperation in industry, but many mutualists, such as Clarence Lee Swartz, looked favorably upon consumer cooperation as well. To my view, the necessity of consumer ownership follows scale. If a natural monopoly arises, due to economies of scale, it is necessary to build a monopsony, and utilize economies of scope, and vice versa. Regardless, and back to our original point of conversation, it is clear that George does not understand the ownership models put forward by the mutualists in this challenge to Westrup.

Mutualists, to be clear, are not atomists. We favor cooperation on large scales. There is no reason to believe that local currencies will not, cannot, or should not confederate for the purpose of inter-regional trade. In fact, this is promoted by mutualists. The idea that some Georgists have about mutualists— having small, atomized economies, where people are slaves to their locality— is complete nonsense. Mutualists are proponents of trade. So long as its membership is voluntary, there is no reason to believe we would oppose the establishment of an international banking confederation.

The conflict between free-banking, hard-backing, Georgists and mutualists is a bit different than that of the classical debate. Part of the conflict between free-banking Georgists and mutualists may be rooted in the fact that mutualists have historically looked at money as labor-credit, or title to potential labor, while many Georgists—especially of the free-banking variety— have looked at money as representing already existing wealth, having a physical basis. That is, mutualists have looked to the potential to monetize any labor, including services which have not yet been rendered, as credit, while many libertarian Georgists have looked only to monetizing already existing capital (such as mined gold) or land as a basis of money. Thus, the mutualists’ arguments are often more pertinent in regard to monetized labor, while free-banking Georgists look at money as monetized capital. Under these conditions, it makes sense that the two would argue; in lending already-existing capital, one is facing a potential opportunity cost, which should derive a fair price of compensation, but in simply writing IOUs for oneself or on behalf of another, as the mutualists have contended, one does not face such a cost. Any charge above the cost of currently-rendered labor is usurious, or unfair, by its very nature.

I feel that conditions like these prompt the argument in defense of the interest on capital-money, as represented by the Georgists and, similarly, thinkers like Bastiat in his debates with Proudhon, while also promoting the argument against interest on labor-money (service), as represented by Proudhon’s side, as well as the arguments of mutualists such as Swartz, Westrup, Tandy, and Tucker, promoters of free and mutual credit. It may also be noted that this distinction is certainly not a hard one. Mutualists are certainly in favor of monetized capital, including gold and any other product of labor (remember, credit money is any kind of paper money, not just fiat), and many Georgists may be openly in favor of mutual credit.

Mutualist criticism of interest is not based entirely on the return that capital receives as capital (though it may include the rent in the capital and profits of privilege), but especially the return the banker receives for simply monetizing, or writing credit toward, that capital. In other words, interest, to the mutualist, is largely a return on capital as means of exchange, but the means of exchange should not carry a value or price in itself, but should only represent the value carried in the things it represents, lest exchanges be hindered from occurring. Again, monetary interest is not the reward commodities get simply for being lent, which would be equal to their opportunity costs, it’s the return that is derived from having exclusive privilege to create currency, or title of ownership (or from other privileges handed down by the state).

As any economist understands, it’s rather difficult to make exchanges without the convenience of money, due to the problem of double-coincidence-of-wants, and so costs of exchange may be reduced by using money, even while paying tribute to the state’s banks for their exclusive right to create titles-of-ownership over land, labor, and capital. Interest is not so much regarded by mutualists as a return for lending one’s own capital, but a return for the exclusive, state-provided privilege to monetize the capital of others, as they are legally unable to do so for themselves. Swartz:

Thus is established the money and banking monopoly which, by eliminating competition, makes it possible for the financier to exact interest for lending, not his own capital, but merely a claim to capital which is secured by the borrower himself.[xxix]

It may also be worthwhile to note that mutualistic thinkers such as Silvio Gesell (also influenced by George) make strong arguments for the elimination of even that monetary interest that Georgists refer to as fair, instead promoting the competitive idea of demurrage. The argument is largely based on agricultural societies and their reactions to spoilage; instead of giving surplus, which would otherwise spoil, to others with an interest-fee attached, which would be unsuccessful, farming societies will give surplus away as gifts, in order to promote good social relations. Such transactions may be loosely liken to buying insurance, or giving credit, as one’s good deeds may be returned in time of need. Gesell noticed that all goods expire over time. Money, representing such goods, he reasoned, should too expire. Thus, he reasoned further, money should carry with it a holding-fee, or expiration, similar to the goods it represents. In such a scenario, lending money would be encouraged not in order to increase at the gain of interest, but in order to pass along the loss faced by expiration. The proper rate of demurrage is, in my view, the rate of expiration faced in the economy.

Outside of monetary policy, the interest referred to by Georgists, being any return on free capital (excluding rent), would also tend to disappear. Indeed, the mutualist, Francis Dashwood Tandy, admits the existence of temporary gains which are not strictly due to manual labor, but to innovation:

If an article suddenly acquires an increased utility, people will be willing to give articles which embody a great amount of labor in order to obtain the more useful article. So the producers of that article, will be able to reap a greater reward for their labor than the other members of the community. This immediately causes a number of the producers of other commodities to leave their old occupations and engage in the one which promises higher remuneration. Thus the supply is increased to meet the demand, until the equilibrium is once more established.[xxx]

Whether innovation is due to an article, or capital, as described above, or to labor, the matter at hand here is that equilibriums are being deviated from. This is where many mutualists face criticism, because this is seemingly a deviation from cost itself, until the price again reaches expected equilibrium. Such criticism relies on a false understanding of the meaning of labor value and cost.

Costs and Benefits

Cost is, of course, anything anyone does not want to do or go through. It is anything undesirable to the individual. As Josiah Warren tells us, cost is the “endurance of whatever is disagreeable.” He says,

Fatigue of mind or body is cost. Responsibility which causes anxiety is cost. To have our time or our attention taken up against our preferences—to make a sacrifice of any kind—a feeling of mortification—painful suspense—fear—suffering or enduring anything against our inclinations, is here considered cost.[xxxi]

Cost is all of the above— forms of labor or disutility—, but such emotions which give rise to cost— such as fatigue, anxiety, preference, suspense, fear, suffering, and endurment— are not able to be objectively or externally measured, but only their effects may be measured so, as emotions are subjective and internal by nature. This leads us to a more subjective labor theory of value that is consistent with marginal utility. As Francis Dashwood Tandy, in his mutualist flagship, Voluntary Socialism, points out,

It should be noted that the labor value does not necessarily mean the actual amount of labor embodied in the identical article, but the amount of labor necessary to produce an article of exactly similar and equal utility.[xxxii]

Thus, to the mutualist, the cost of labor itself is subjective in nature, and, again stated by Tandy,

As the margin, or desires which are left unsatisfied, increases, the price decreases. Thus it is the ‘margin of utility’ which determines the price. [xxxiii]

With this understood, any positive deviation from expected equilibrium a firm experiences in the free market may indeed be unexpected, but it is not a deviation from the cost-principle, as such a return from entrepreneurial innovation is not due to privilege, but brainwork. The innovation has reduced the costs for others in society. When others pay the fair, free market price, they are doing so because it is less costly than doing the work themselves. As Tandy has already pointed out, though, there are plenty of outsiders looking to take some of the newly found return that the entrepreneur has found; and any return due to innovation will soon be lost to replication in the market. Thus, the entrepreneur’s gains, as deviating from expected equilibrium, are neither profits, according to the mutualist definition— being above cost—, nor permanent under a free market. These gains do, however— if not profits—, deserve their own moniker, which we will be getting into later.

The Mutualist-Georgist Connection

As hopefully demonstrated, the main disconnects between mutualists and Georgists, or at least geo-anarchists, are not in scenarios and outcomes, but rather in the language used to describe them, or in their practical application. Mutualists tend to refer to taxes, interest, rent, and profit in general as usurious forms of income, gained only by the privilege of the state, but they have also always maintained caveats and provisos to such statements, allowing for such things as “enough interest to cover costs of operation” and “profits of enterprise.”

Georgists have always condemned unfair banking and industry (though they are divided on its fix), and have criticized their returns ferociously, but have never adapted the language to refer to the returns of such privilege, as the mutualists have done when referring to prices above cost as taxes, interest, rent, and profit or, collectively, as usury.

Mutualists have always maintained a strong position against land speculation and monopoly, opting instead for a system of occupancy-and-use, which has often been loosely defined, and has long been in need of further clarification. They are correct, in my view, to condemn the statism of those guilty Georgists, but those Georgists who have transcended the statism of George himself offer mutualists the further clarification of occupancy-and-use they have long needed.

In rejecting Georgist proposals whole-heartedly, instead of drawing the positives from them, most mutualists have ignored the problem, not of absentee-landlordism and rent collection, but of the rent that is collected by landlords from the land they are personally occupying and using, which is brought to market and traded for goods and services that were purely returns on others’ labor and capital (where marginal land is used). While they are correct to reject statism, the mutualists have been short-sighted in their rejection of full positive liberties not just to land as space, but to land as resource. In other words, mutualists are often wrong in rejecting common rights to economic rent, while they are correct to support common rights to having one’s own area of control. Such rights, under the conditions of differing grades of land, must be granted socially, as they impose restrictions on the positive liberties of others’ use. John Locke, oft-cited father of the homestead principle:

Nor was this appropriation of any parcel of land, by improving it, any prejudice to any other man, since there was still enough and as good left, and more than the yet unprovided could use. So that, in effect, there was never the less left for others because of his enclosure for himself. For he that leaves as much as another can make use of does as good as take nothing at all. Nobody could think himself injured by the drinking of another man, though he took a good draught, who had a whole river of the same water left him to quench his thirst. And the case of land and water, where there is enough of both, is perfectly the same.[xxxiv]

Despite all of the arguments between Georgists and mutualists, there is certainly a common populist and libertarian heritage to be found in both schools of thought. Both are concerned principally with the freedom of the laborer over their product, and indeed both ideologies focus on land and banking reform. Proudhon, the father of mutualism, said of the matter, “The right to product is exclusive; the right to means is common.”[xxxv] This is not much different than the argument that Georgists put forward. Both schools of thought see validity in a social claim to land, and both see validity in the individual’s claim to their own labor and product. The mutualist-Georgist connection is one of practicality rather than description, and both would do better to learn to read, not just the words of the other, but, the meanings behind them, in order to coordinate descriptions for the general public. At the same time, the debate has led to this synthesis, which would not be possible without it, so, as with all conflicts, which most often result from misunderstanding, perhaps both Georgists and mutualists should be thankful, as the disagreement has incentivized discussion and allowed for the exchange of ideas and possible resolution, resulting in hopeful unity between both groups of libertarian populists.

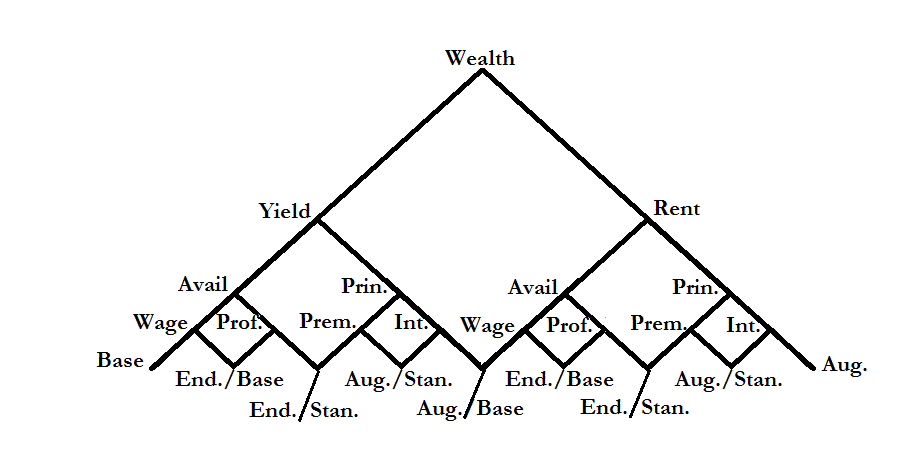

The Factors and Their Returns

As most of the debate between mutualists and Georgists revolves around words and their definitions, in the following sections I will be using the law of rent to propose new usages, which may be adaptable to a new language of geo-mutualism. I will also be clarifying a particular concern I have with the usual assessment of rent.

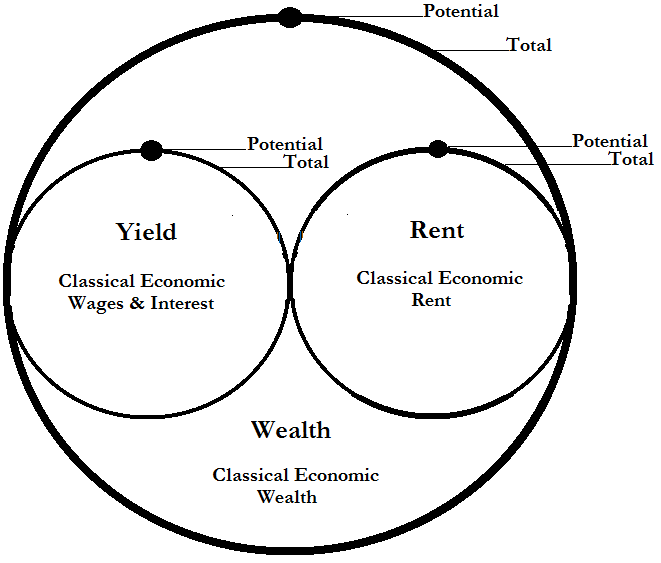

There are three factors of production according to classical economics. These factors are land, which is natural resources; labor, which is human effort (whether it be mental or physical); and capital, which is the mixture of these two things. From these factors can be derived their returns. The return on land is classically called economic rent, the return on capital is economic interest, and the return on labor is called economic wages. These returns can be measured by knowing the productivity of land and average intensity of labor and capital.

Say, for instance, that there are four plots of land, of varying grades. With average intensity of labor and capital, the land can produce 4, 3, 2, and 1 units. The margin of production is generally treated as being equal to the classical economic wages and interest (which I will be renaming later in order to synthesize Georgist and mutualist thought). When these are subtracted from the total productivity of a piece of land (using average intensity of capital and labor), we get the economic rent. Like such:

| Total Wealth | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Wages/Interest (Margin of Production) |

1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Economic Rent | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

From the Georgist perspective, wages and interest are the fair returns derived from labor and capital, and rent is derived simply from owning land. Land cannot justifiably be owned, however, as humanity did not create land, but exists instead at its mercy. Georgists insist that economic rent be paid to the community at large by way of taxes or dues, to be distributed by dividends or public services. This is all good and well, in my opinion (except taxes).

Georgism Too Soft on Rents

My break with most Georgists comes when other influences are added, such as increase or decrease in intensity of labor and capital productivity. Say, for instance, the person who takes the best piece of land and pays 3 units of rent to the community works twice as hard. Here’s what we’re looking at:

| Total Wealth | 8 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Economic Rent | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Total Income | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

The problem here is that, though the worker is producing double, and the others are producing average, he or she is receiving quintuple the amount of everyone else. If their labor was applied to the margin, they’d receive only their duly double. Of course, it could be argued that the double effort of the worker changes the average productivity, and thus the rent, which is a fair assertion. It does. If the other workers above can produce only one unit of value on the worst land, and the worker laboring twice as hard can produce two, that brings the average to 1.25 (5[1] ÷ 4 = 1.25). In this case, the rent on the worst land, as calculated with only average labor, is 0, on the second to worst is 1.25, the next to best is 2.5, and the best is 3.75.

| Total Wealth | 5 | 3.75 | 2.5 | 1.25 |

| Wages/Interest (Margin of Production) |

1.25 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 1.25 |

| Economic Rent | 3.75 | 2.5 | 1.25 | 0 |

With the new average, the worker who produces double their peers, who work at 80% of the average (1 ÷ 1.25 = .8), still gets more than double return on their labor. It would look like this:

| Total Wealth | 8 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Economic Rent | 3.75 | 2.5 | 1.25 | 0 |

| Total Income | 4.25 | .5 | .75 | 1 |

I don’t think it’s fair to consider the amount of increase the best worker has had due to land as wages and interest (I’m going to be clearing these up, too). Instead, the spurious portion of their income that is above their proper rate of return should be considered a part of the rent. There’s also the new dilemma that, though each of the three workers who exerted labor at 80% (relative to the average) exerted the same amount of labor, two are forced into plots that make them receive less than the other, with one making half the amount and the other making three-quarters of it.

| Total Wealth | 8 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Economic Rent | 3.75 | 2.5 | 1.25 | 0 |

| Total Income | 4.25 | .5 | .75 | 1 |

I think there may be a better approach than simply charging rent based on the average value of the land minus the margin of production. Instead of using economic rent— as based on the average productivity of a piece of land using average labor, and then subtracting the margin— as the total end-result of rent, it may be best to use it as a factor in a larger equation. In such case, the total rent of the land would not simply be the average productivity of the land minus the margin of production, but the economic rent times the productivity rate of other factors of production (labor and capital). This means the economic rent times the labor and capital power. If a worker works twice as hard as their peers, the total new rent will be the classical economic rent times this effort (1.6, see next paragraph). The same is true of a worker who works only half as hard (0.4). In this case, the best worker, who would produce 2 units on the margin, labors 160% of the productivity of the average worker (1.25) on the best land (first column), or 200% of their peers (2 x 0.8), resulting in 8 total wealth (5 x 1.6 = 8; the average worker produces 5 on the best land), 6 of which is the total rent (3.75 x 1.6 = 6). I will from here on refer to the factor of economic rent as potential rent, and the outcome of the larger equation as total rent.

Don’t let this get confusing, there are differences in the models of average productivity and true productivity. The best worker works twice as hard as their real, shown, peers (2 vs. 1 on the worst land, 8 vs. 4 on the best), but only 60% more than the average ([which is a non-existent, unshown, person in this model] 2 ÷ 1.25 = 1.6, or 160% of the average). So, while the best worker may produce 200% (2 ÷ 1 = 2) of the others, who only produce 1 on the marginal land, by producing 2, they produce 160% of the average (non-existent) worker, who would produce 1.25 units (5 ÷ 4 = 1.25; 5 because of three who produce 1, and one who produces 2, making 5; and 4 because it’s four individuals), on the marginal land (2 ÷ 1.25 = 1.6).

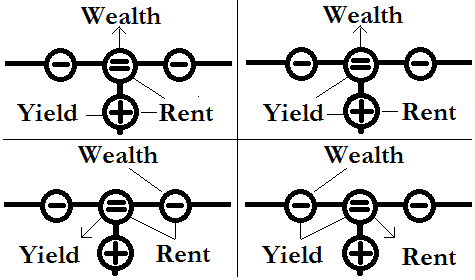

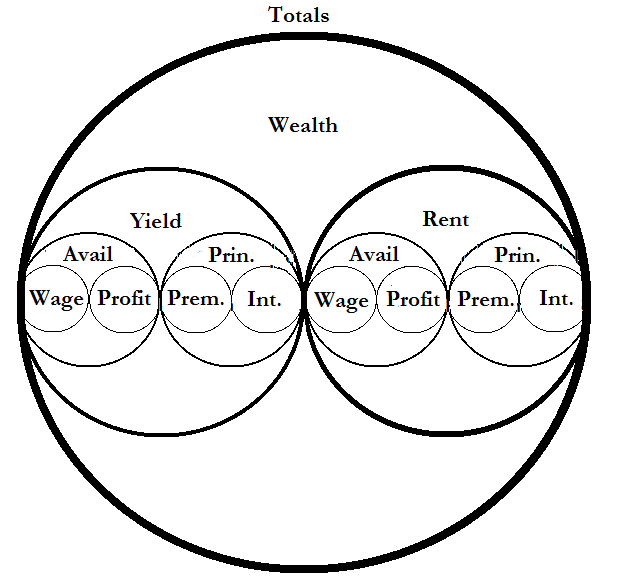

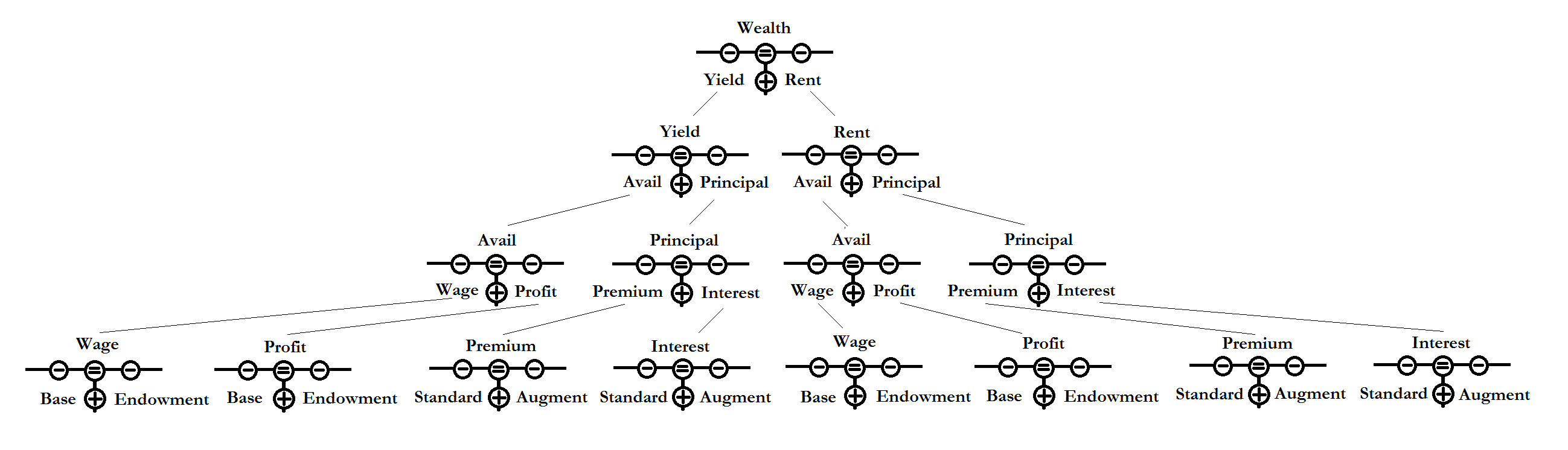

Yield and Rent

Just the same as done with rent, it’s possible to use the classical economic wages and interest (which will be renamed), as measured by the margin of production with average labor, to determine the true return that is due compared to one’s peers. Instead of wages and interest, I will from here on be referring to classical conceptions of them, together, as yield. Yield, then, is the portion of the return on land that is due to labor and capital, and encompasses classical economic wages and interest.

From this point onward I will be referring to classical economic returns as potential returns. In other words, because we will be using the classical economic returns (such as classical economic rent) as factors in larger equations (as stated in section ‘Georgism Too Soft on Rents’) and they will not be considered the total return, we will refer to them as potential returns. In regards to yield and rent, the classical economic rent is synonymous with potential rent, and the yield is equal to the non-spurious (not due to rent) classical economic wages and interest.

The potential (or economic) yield is equal to the margin of production (as measured with average labor), or non-spurious wages and interest, and the total yield is the outcome of yield as a factor. The rent (coming in potential and total, as well) is the portion that is simply due to having a better grade of land. The yield is always free from land-rent, but may include profit (herein considered a return on monopoly labor) or interest (herein considered a return on monopoly capital), which I will get into later.

yield is equal to the margin of production (as measured with average labor), or non-spurious wages and interest, and the total yield is the outcome of yield as a factor. The rent (coming in potential and total, as well) is the portion that is simply due to having a better grade of land. The yield is always free from land-rent, but may include profit (herein considered a return on monopoly labor) or interest (herein considered a return on monopoly capital), which I will get into later.

Now, we’ve said that we have four actors, three of which produce 1 unit of wealth on the margin of production, while the other produces 2. We’ve said further that the best worker takes the best land (in line with comparative advantage, increasing productivity for all), and produces the most wealth. If you multiply the potential wealth (yield and rent) with the potential avail (classical economic wages, we’ll be getting into this soon) of a marginal (the worst) worker you get the marginal total wealth. If you multiply the potential wealth with the potential avail of another worker, you get their total productivity of wealth. If capital is involved, potential principal (classical economic interest) must be factored in as well to get the wealth. This example is not currently using capital, just labor. From now on I will use A to describe the best worker, and B, C, and D for the other three marginal workers.

| Participant | A | B | C | D |

| Potential Wealth | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Potential Avail | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Total Wealth | 8 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

We can split land’s (using the productivity or effort of a marginal worker) potential yield from potential rent, and when multiplied by the other factors, such as labor and capital, this will give us the total yield and total rent, which, when combined, gives us the total productivity or total wealth.

| Party | Potential | Effort | Total | Total | ||||||

| A | 3.75 | Rent | X | 1.6 | = | 6 | Rent | or | 8 | Wealth |

| 1.25 | Yield | 2 | Yield | |||||||

| B | 2.5 | Rent | 0.8

|

2 | Rent | 3 | ||||

| 1.25 | Yield | 1 | Yield | |||||||

| C | 1.25 | Rent | 1 | Rent | 2 | |||||

| 1.25 | Yield | 1 | Yield | |||||||

| D | 0 | Rent | 0 | Rent | 1 | |||||

| 1.25 | Yield | 1 | Yield | |||||||

Profits & Wages and Interest & Premium

It is possible to further break the total yields and rents from labor into profit or wages and, if using capital (which we aren’t yet), premium or interest. Profit and wages are together called avail, and premium and interest are together called principal. Profit and interest are herein considered returns from privileged labor and capital, while wages and premium are returns from fair labor and capital. Say, for instance, that A is twice as productive as everyone else because there is a law which benefits them, either through licensing, taxes, subsidy, zoning, or another mechanism. Say they work the same amount, and all of them produce the same product, but all of the labor is in setup and teardown (and since we’re using capital now, let’s make everyone using the same capital and capital-privileges, so it can be negligible to the equation, and ignored for the moment), meaning regardless of the amount sold, the labor for the day is the same. Because A gets tax breaks, subsidies, better zoning laws, has a license, or what have you, they get more business, with the same effort. The return that is not due to such privilege is wages, while the return that is due to such privilege is profit. If it were instead to be due to capital rather than labor, the privileged return would be interest and the fair return premium.

Some seemingly fair returns may be spurious. For instance, wages and profit and interest and premium can be yielded or rented. Those returns that are profited, interested, or rented are largely spurious returns; rented-premiums, interested-wages, and profited-base, for instance, are unfair returns. See below for rented wages:

| Party | Economic | Pot. Rent and Yield | Return | Total | ||||||

| A | Effort | 0.8 | X | 3.75 | = | 3 | Wages | or | 6 | Rent |

| Privilege | 0.8 | 3.75 | 3 | Profit | ||||||

| Effort | 0.8 | 1.25 | 1 | Wages | 2 | Yield | ||||

| Privilege | 0.8 | 1.25 | 1 | Profit | ||||||

The amount of profit A is gaining totals to 4 (3 + 1), and their wages also equal 4 (3 + 1). If we were to go through the other individuals, B, C, and D, who have no privilege, they’d only have wages, without profit. Profit is unearned income. Obviously rented-profit is unearned, as it is profit from the rent (as above, .8 x 3.75 = profited rent), which is always unearned, but yielded-profit is also unearned income, as well as rented-wage. This individual, A, when compared to the others, has worked the same amount as the others, who, on the margin, produce only 1 unit of wealth. That is exactly the amount of wealth that is left when one takes away all rent (6) and remaining profits (1) from the equation. The only fair return in this equation is the yielded wages on the third line down (.8 x 1.25 = 1), while the first line is waged rent (.8 x 3.75 = 3), the second is profited rent (.8 x 3.75 = 3), and the last is profited yield (.8 x 1.25 = 1).

Base & Endowment and Standard & Augmented

Obviously, there will be some workers who are better than others out of their own intrinsic capacity, and not out of privilege, and who thus deserve a higher return, but, in such a case, the difference, which is not due to privilege, but to ability or effort, is better not known as profit, but as something else. I’ll use the term endowment. Therefore, wages are composed of endowment and base, base-wages being the wages received on the margin. The same is true of profit. It is composed of base and endowment. If there are those who make more than others, while sharing the same privilege, gaining profit, they have gained endowed-profit atop the base-profit that the marginal privileged worker makes.