Giving Consent

A great deal of my work centers around the concept of consent. While ideological monikers such as “dualist pantheism” and “geo-mutualist panarchism” have been found to be of great use, I have tied these together under the umbrella, The Evolution of Consent, for a reason. Consent is universally desirable.

Consent is an intrinsic mechanism of human evaluation. That which has one’s consent is exciting at best, and is at least tolerable. If an individual truly consents to something— they are informed, and they are not under duress—, they are making the decision they value the most, considering the overall context. This being the case, any ideology which establishes itself under the umbrella of consent must operate in a manner that is in accord with the will of all who participate. This is no small task! Such a project must account for differences of value-perspectives, and must reconcile those perspectives. It must be flexible and capable of withstanding and nurturing diverse viewpoints. Dualist pantheism and geo-mutualist panarchism are attempts to do just that.

Rather than simply addressing the ideologies which are based in it, in this essay I’d like to pay attention to consent itself. Particularly, I’d like to address the issue of where consent originates. Who owns the consent? That is, for a particular action to be taken, who must be addressed for permission to be granted?

Consent is directly connected to what one wants, what one wants is connected to outcomes, and outcomes affect one’s happiness or flourishing. In the end, as individuals are the best judge of their own taste, consensual and voluntary means are the best way to get what one wants, which is a future outcome that makes one happy. Rarely, if ever, does something forced onto an individual, without their consent, have positive or desirable outcomes for the individual, as they see it. That is, rarely, if ever, does one get to future outcomes that they find satisfying, without first consenting to those outcomes to some degree. My goal is to create a happy society, wherein people are allowed to approach the ends they desire. This entails a mass increase in the amount of consent given.

What does it mean to give consent, and who must give the consent? Consent is given when something meets one’s approval. Most situations involve many people, however. Whose approval must be sought? Ideally, everyone’s approval is sought. However, this cannot always be the case, at least not in every specific moment. Is there a way to have consent without full collaboration? If not everyone, in worldwide collaboration, how can we allocate matters of consent? How do we decide whose consent matters?[1]

I believe the best way to decide whose consent matters is to take a look at who is most affected by the decision, and rather than seeking full agreement, compromising and allocating liberties equally. Ultimate consent is enthusiastic group consent, but it takes time to build. This being the case, we must compromise for the time being, while always moving toward the end goal. This means, instead of looking to the group for consent in every matter, allocating decisions to the parties most affected. While we are moving toward a larger group agreement, we must find an organic means of compromise. This compromise allows people’s actions to be pre-accepted, so long as they fall within the guidelines.

Compromise and Collaboration

There is potentially a place wherein everyone shares in the same desired outcome with enthusiastic consent and full collaboratory effort, and compromise is not at all needed. Such a unitary singularity would, indeed, be heaven, but it is hard to come by. While I do believe that there is an ultimate reconciliation to be had, I do not believe it intelligent for us to treat situations as if such a moment has already been reached. In other words, I do believe it possible to reach an agreement that ultimately satisfies all to the fullest extent, but I do not believe we have yet made it. Such an ideal future simply does not describe the material reality of the present. This being the case, we are best occupied by concerning ourselves with the manner by which we can start bringing such an end to into being. We may only concern ourselves with its approach, lest we be content to wallow in the misery of our present condition as defeatists and fatalists. This entails a soft transition, the bridging of the reality of conflict and the ideal of collaboration. Indeed, time would have it no other way; gradual change is in her nature.

Still, the reality is that enthusiastic collaboration is difficult to approximate; a product of our material separation as individuals, and the differences of perspective this entails, both objective and subjective (but especially subjective). Where such enthusiastic collaboration can be found, it should be celebrated, studied, and its methods mimicked. Where it cannot be found, one should not be contented to be defeated by the present, and accept conflict as a given, or a “brute fact,” but instead should ask, “What are the conditions fertile for enthusiastic collaboration?” and, relatedly, “What conditions do not yet meet the description of enthusiastic collaboration, but serve as a middle ground between that and continued conflict?”

Is the middle ground to be found between conflict and collaboration not also the transitional fertile ground for further development into collaboration? That is, if we are to approach this in terms of natural cycles of succession, would it not follow that the middle ground between conflict (death) and collaboration (life) follows the same rules of generation and succession as that between the desert (death) and the jungle (life)? Does it not follow that as the savannah both succeeds the desert, and lays fertile grounds for the jungle, that the middle ground between conflict and collaboration will follow a similar order of succession, and will be not only a transition from the old, but fertile grounds for the new? We have then only to find this middle ground! What will it be? As the prairie grass and the clover take over the desert, it covers and nitrifies the soil, making it easier for shrubs and trees to be established. Likewise, it will be compromise that succeeds conflict, and which will provide the fertile grounds for collaboration.

An individual cannot feel safe in a compact in which they are forced by anything other than natural conditions, which themselves are not induced by a human. As soon as a human institution forces one’s membership, or otherwise forces its dictations on an individual, the grounds are set for much concern. One immediately begins to question the motives of an institution which gains influence by compulsion rather than by attraction alone. If it has to be forced, it probably isn’t wanted, and if it isn’t wanted, it is not valued, nor does it lead to happiness. However, as it regards voluntary consensual behavior, individuals who are given the space to play out their own values—that is, individuals who have compromised among one another— are free to experiment, and to share their results with others. This induces collaboration by demonstrating the benefits of learning from others, and putting different ideas together. It removes the threat of forced collaboration with those who would otherwise do harm. Compromise provides a safe space from which collaboration may develop, and benefits may be felt incrementally. One may, as it were, dip one’s toes into the water of collaboration, before leaping head first into its depths.

Compromise is probably best understood as agreeing to disagree. This is different from collaboration, which is built on more full agreement. While collaboration entails the sharing of goals and space, compromise entails the fair division of space, wherein one can meet one’s own goals with the least interference of the other. While collaboration is the ideal we ultimately seek, compromise is the foundation it must be built upon. In those circumstances that individuals gain in combination, they will combine their efforts voluntarily.

Sometimes that which is wanted by individuals contradict. In such a case, the freedom, or consent, of one individual, may infringe on that of another. This is a case of not having reached unity with the Absolute, wherein all perspectives are aligned in ultimate reconciliation. Indeed, we are approaching it, but we are not yet there. Still, there is no need to be contented with continued conflict; compromise provides some reconciliation, and a greater degree of consent, even if it does not amount to enthusiastic collaboration. It does provide the grounds from which such collaboration may be safely and confidently approached, however.

While it may not be possible, or socially desirable, to live a life of complete freedom in the present moment, one may begin to understand the conditions which begin to allow for the maximum amount of freedom that can exist without contradiction. In other words, because one’s desires conflict with others, and because freedom is connected to the ability to do what one wants, complete freedom for one may negate freedom for others. This being the case, the pursuit should not be a matter of complete freedom, but the maximum amount of freedom that can be had in the present moment, in compromise.

Equal Liberty, Negative and Positive, Protected by Contract

The maximum amount of freedom available to the greatest number can be determined by the amount of freedom that can exist without contradiction. This is best described in the principle of equal liberty, which suggests that liberty should exist only to that degree that it is available to everyone in equal quantity. In other words, everyone should have an equal amount of freedom, which means that the freedom of one should stop at taking freedom from another. According to the principle of equal liberty, everyone should have the very same liberties, and no one should have privileges that others do not enjoy. This is not a doctrine of complete liberty, or complete equality, but one of equity, or equality of opportunity. The principle describes a condition under which all have an equal right to express their natural endowments.

It is not enough, still, to allocate liberties equally, but they must be allocated equally in the most appropriate fashion. Equal meddling in one another’s affairs, equal intrusion into the privacy of others, these are not the conditions conducive to enthusiastic collaboration, as they forsake the necessarily preceding principle of compromise, or the space for each to be their own. Equal abstinence from solidarity, equal neglect for one another’s well-being (even if not a direct offense or attack), neither are these conditions of the soulless what I am after. I am neither after neglect nor forced combination, but compromise and voluntary collaboration. The fertile grounds of fair compromise and voluntary collaboration are found, instead, in the proper treatment of human liberty.

Human liberty takes two fundamental forms, positive and negative. There is the liberty of action, and the liberty of abstinence; to act, or not to act. This can also be understood as the liberty to act upon, which is positive, and the liberty not to be acted upon, which is negative. Like supply and demand, these fundamental and polar forces are opposed to and contradict one another, but, also like supply and demand, this contradiction is ultimately reconciled; in this case, in the equality of liberty. Individuals best have the liberty to act without being acted on by others, and are best restricted from acting on others. Such a condition of equal liberty is conducive to the maximum freedom for the maximum number. In other words, such conditions provide fertile grounds for the maximum amount of consent, and, it follows therefor, happiness.

Society exists by compact, with jurisprudence as its foundation. Societies are bound by laws, which designate appropriate and inappropriate behaviors. These laws may take many forms, and may enforce a plethora of different systems. The duty of a just social contract is to allocate freedoms in such a manner that they are equal and appropriate. As we have determined that compromise is the most appropriate transition from our present conflict, and also the most fertile grounds for future collaboration, the most appropriate equal allocation of the two forms of liberty— negative and positive— will allow for the maximum amount of compromise, but will not force it, instead setting the conditions for further development into voluntary collaboration.

Contracts develop firstly to protect negative liberties, and then to ensure positive influence. The most highly developed contracts accompany the highest degrees of collaboration and shared vision. This can be seen in the fact that property rights preceded democratic process in modern societies, that animals develop claws, fangs, spines, and more, before they develop cooperation and ethics. The natural process of life stretches toward a higher degree of satisfaction, the highest level of which is found in voluntary collaboration for mutual benefit, the lower levels of which being found in personal autonomy and reciprocal exchange.

Because contracts entail rules, or deontologies, it is necessary to analyze the application of such deontologies. As these deontologies relate to human behavior, if they are to be desirable, they naturally and necessarily must describe the proper conditions and limitations of human liberty.

An individual entering into a contract will naturally assess the value of the contract in relation to meeting their own ends. That is, an egoist—which all naturally are— will unsurprisingly assess the utility (both qualitative and quantitative) of any contract that they enter. Because contracts naturally lay out rules and procedures, this utility is made in regard to deontologies. These deontologies are evaluated consequentially according to their perceived ability to provide desired outcomes. Those deontologies which are found universally acceptable—that is, those which meet the grounds for the categorical imperative— are found the most utilitarian by the egoist. Equal liberty fits such a standard.

If equal liberty is to be our standard, it must be applied as it plays out in human action. This being the case, we must allocate liberties to certain parties involved in situations, and we must allocate these liberties fairly and in a way that allows for the greatest amount of compromise. Further, this entails deciding who gives consent, and therefor under what conditions they are the most affected, earning them exclusive or primary say.

The Principle of Most Affected

Clearly, anything relating to bodily experiences most affects the individual undergoing the experience. There are two forms of bodily experiences. There is thought, a noumenal experience (or “inperience,” if you will); and then there is sensation of external phenomena. These two forms of experience lead to two forms of truth, subjective preferences and objective facts. Subjective preferences are truths held internal to the individual. Individuals differ greatly in their subjective preferences. Objective facts, however, can often be seen from the outside, and referenced by all who have the means. Objective facts are most associated to inanimate objects, while subjective preferences are matters of consciousness. This being so, we must treat conscious beings with a different regard than we do inanimate objects. We must seek their approval on matters of quality. Consent can only be given by living beings, which have preferences. Objective affairs are simple realities best approached through empiricism, but subjective matters, such as those relating to value systems and preferences, are not so easily determined.

Rarely do individuals see exactly eye to eye on matters of preference or value, without a considerable amount of communication. This being the case, the subjective satisfaction of the individual, and all that is entailed by it, must be sourced from within the will of the individual, and can be demonstrably accessed from without only by way of consent. The reality of separation gets in the way of ideal outcomes.

Humans exist as individuals within groups. It is crucial to separate individual and communal decisions. What decisions are necessarily personal decisions, and which are up for common approval? Again, it is necessary to look into matters of who is affected by the decision. Because we have already drawn a line of demarcation between external and internal experiences, we will approach the question from this angle.

Who is most affected by internal noumena, such as a thought? Certainly, so long as it remains a simple thought, the individual alone is affected by it. What of external phenomena, such as physical sensations? Physical sensations, which are external to the individual, have the potential to be sensed by anyone in the proper vicinity, even if only indirectly so, as by eyesight or smell. In other words, physical experiences are more often a matter of common concern than individual preferences. This being so, matters of internal preference belong most properly to the individual, while matters of external sensation most properly belong to society at large. In other words, society has the most proper say in the area of the non-human environment, while individuals have the most proper say in matters relating to their preference of action.

The human experience includes our subjective preferences, which we are always acting in favor of to the best of our abilities, but these always rest atop objective realities, which can enable or hinder our preferences, depending on the reality itself. In other words, we have our desires (many of which are instinctual, such as the desire for food or sex), and then we have the environment in which those desires are placed. We have the human being, and their surroundings. Direct effort can only be experienced from the inside, but our surroundings are easily accessed from without. Economically, and in terms of justice, this entails the ability for people to make all decisions regarding their efforts as individuals, and all decisions regarding the management of environments to properly-scaled groups, who share those environments.

In order for the conditions of compromise to be met, individuals must be allowed to play out their own goals, and must have the space with which to play those goals out without unnecessary interference. This means that individuals need to have access to land, and must be free to do what they wish with their own labor. Individuals who are forced to share space, or who are forced to share goals, will do what they can to end such forced collaboration; while individuals who voluntarily join in combination for the gains perceived will enthusiastically do what they can to further collaboration. Still, a degree of association is completely necessary, for the settlement of disputes, and the allocation of freedoms, especially as it regards natural resources.

Common Land, Personal Labor

Any proper social contract will be established upon consent, and will be maintained through consent. Its establishment should be determined by collaborative effort and complete consensus, but this social contract should describe how subsidiary decisions may be made in the absence of the whole, but with its pre-approval. The consensual establishment of the contract is best done through voluntary memberships with probationary periods, wherein one has time to be fully informed before membership becomes solidified. After the establishment of the contract, subsidiary decisions should be allocated to individuals or groups, as found appropriate. We have determined that equal liberty should be our standard, and should be applied in both negative and positive forms, with positive liberty given primarily to groups in the area of land, and negative liberty to individuals in the way of their labor. This being the case, land is best regulated by common consent, and allocated by way of common bids, with common collection and dispersal of its rents; while labor is best left completely unregulated (except by common law and the principle of fair regard).

Who should give consent? In matters relating to resources, groups have a positive right to its management, and so consent begins with groups that utilize those resources. That is, in matters of natural resources, it is collectivities that have a right to make decisions; while in matters of human effort, the individual alone has a negative say in its direction. However, this only establishes who best gives primary consent. That is, groups have the initial say in the management of land, and individuals have an initial say in the direction of their labor. This does not suggest that land is best managed by groups, or that labor is best managed on an individual basis. It merely suggests that any individual use of land is best consented to by the whole, and that any collective demand for labor is best consented to by the individual. For this reason, property rights should be allocated according to contract to individuals from the whole; while collaborative activities should be consented to by the laborer, thereby relegating the activities to conditions of utility.

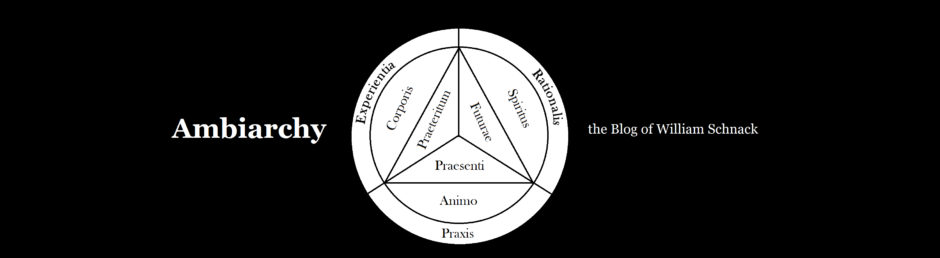

There is a kind of spiral effect created in this model. The materiality of land is grounded in the whole, but becomes dispersed; and the ideality of labor exists in separation, but comes together for mutual benefit. This reflects the natural cycles in our own cosmos; the entropy of materiality, and the syntropy of living systems governed by ideality. Living things must naturally start from their material conditions of separation, only to find joy in the benefits of willful collaboration and coming together in a higher unity; while land must naturally begin under the unity of the whole, only to be dispersed about. Purely material things must always tend toward dispersal, while spiritual beings always strive for unity in some form. Both movements are necessary for the composition of the whole.

[1] It can be the case as far as it relates to the rules, however, such that every situation which occurs is pre-approved so long as it occurs under the proper guidelines. We will address this in a bit.