Introduction

What is The Proper Rate of Money? Money has always carried with it a price of some sort. When one is loaned money, one is asked a price, called interest, for the loan. If one mortgages their things, there is a seigniorage fee which often must be paid. At times, governments will devalue currencies by way deflation, or increase their value by way of inflation. What is the proper rate of money, though? That is the question which is being asked. How much interest should really be charged? How much should the price of money stray from the value of its basis? How much inflation and deflation should occur?

The Nature of Money

In order to examine the proper rate of money, we must begin with its nature. Today, money is simply a title which is backed by goods and services. It has value to its holder only because of its redeemability in those goods or services.

In many ways, money can be thought of as an IOU. As Thomas Greco, Jr. suggests,

The money issued [by a bank] can be thought of as an IOU that the buyer uses to pay for the goods and services he bought. That IOU may be passed along from hand to hand as each recipient, in turn, uses it to pay for his or her own purchase. Eventually, it must come back to the originator of the IOU, who redeems it by selling something of value and accepting the IOU as payment.[i]

An IOU is a form of simple contract, which allows exchanges to occur by way of agreement. Thomas Greco, Jr. says,

We can see […] that the essence of money is an agreement (a consensus) to accept something that in itself may have no fundamental utility to us, but that we are assured can be exchanged in the market for something that does. Whatever we use as money, then, carries information. The possession of money, in whatever form, gives the holder a claim against the community of traders who use that money. The amount of money informs us about the magnitude of that claim. But the legitimacy of that claim also needs to be assured in some way. The possession of money should also be evidence that the holder has delivered value to someone in the community and therefore has a right to receive like value in return, or that the holder has received it, by gift or other transfer, from someone else who has delivered value. Unfortunately, throughout history, this ideal has been subverted in various ways depending on the kind of money used at the time.[ii]

When one writes an IOU to another person one is writing a promise of future repayment. One is, in effect, writing a deed to their labor. This deed can be a claim to efforts of their past labor, as in a currency backed by product, or it can be a claim to efforts of their future labor, as in credit backed simply by good will. The IOU can read “IOU two drinks when we get back to my place” (past labor purchase, backed by hard goods), or “IOU one 20 square-yard lawn mowing” (future labor effort, good will), for instance.

The entire purpose of writing an IOU, or issuing credit, is to allow an indirect exchange to occur in absence of direct exchangeability. IOUs allow exchanges to happen when one or more of the parties do not have anything to directly exchange in the moment, but still have something of value, such as good will for the future or something in stock somewhere out of hand. For example, if person A has something to trade, but it’s at their house, they may write an IOU. If, instead, A wants something B has, who doesn’t want what A has, this is called a problem of double-coincidence of wants. IOUs can be written in this case, as well. It is best done according to the method of generalizing IOUs, rather than by using personalized IOUs, however.

At one time, money was backed by gold, and was redeemable in gold, but this proved insufficient for large volumes of trade, as the value of all of the gold in the world does not equal the value of all necessary exchanges in the economy. Today, money is backed more abstractly. The US dollar, for instance, is backed largely by the GDP (Gross Domestic Product) as a whole, which includes all of the work at the movie theaters, grocery stores, warehouses, construction sites, and anywhere else in the nation.[1]

Like tickets being redeemed for a choice of prizes after having been won in arcade games, we have many options in how to redeem our dollars. Just as tickets can be used for various prizes, dollars are not tied to one good or service alone, but represent a percentage of all goods and services in a given economy (including involuntary ones, provided by way of taxation). Dollars are generalized value redeemed for the specific value of labor, living space, or commodities.[2] A dollar is an abstract unit of measure. No longer is it only redeemable in gold; it is redeemable in French fries, car washes, rent, and, ultimately, in “protection,” by way of taxation (the state is a protection racket).

Essentially, banking, since money is backed by goods and services in the GDP, is the business of writing generalized IOUs on others’ behalf. The reason for generalizing the IOUs, of course, is for the ease of exchange. Keeping track of specific IOUs, and redeeming them accordingly, is much more work than keeping track of generalized IOUs. Personalized IOUs are also less trustworthy from strangers than generalized certificates ensured by a third-party. The banker, as a third-party, takes responsibility for ensuring the stability of the currency, by applying strict standards to credit and lending. This allows credit to be distributed outside of one’s immediate circle of friends, who otherwise have no reason to extend trust. [3]

IOUs can be generalized in a number of ways, but normally use a unit of account which is universal and which has no specific backing. Instead of being backed exclusively by one item, like gold, the unit, in a manner similar to the US dollar, is an abstract measure of value, which “floats.” A dollar can buy a number of whole things, or a fraction of other things. In other words, three dollars may buy a person a bagel, or it may buy them one percent of a bicycle. Tomorrow, however, the price may change, depending on supply and demand. This issue will be further addressed later in the essay.

We are familiarized with the general idea behind money and, in due time, we will turn our attention to the nature of opportunity costs as they relate to interest, but, first, a necessary discussion on words and their intentions.

Speaking the Same Language

Before we continue any further, we must lay semantics aside and look at intentions. Words mean different things to different people, thereby carrying many meanings.

One of the main topics of which I will be discussing in this essay is that of interest, which can generally be thought of as lending at a price. Specifically, however, I may address interest in another manner, which is consistent with that of my mutualist heritage. As I address interest, I will be discussing the interest I oppose as well as the “interest” I support, while simultaneously stating I oppose interest in general. This may be confusing at first, but let’s take a deeper look at why I take this position, before we continue, in order that we may speak the same language and will be able to mutually address the topic at hand.

Words are often caught between meanings, and the word interest is no different. The meaning of the word interest, like the meaning of cooperation, as described in “Two Incentives of Cooperation,” has been confused, conflated. This is a drastic error, though! This error is as dire as mistaking theft for purchase. If theft described any exchange, be it voluntary or coerced, such would be the position of the word interest in our daily habits. Indeed, this is the role it plays, when it describes both fair and unfair returns to capital.

It appears that, if interest is to be considered a return on any form of loan, some forms of interest are fair returns, while others are not (as determined by their relationship to cost). In “Interest and Premium” I have separated these returns into interest proper, which I consider to be unfair, and premium, my term for “fair interest.” The difference between the two is a matter of monopoly and returns above cost, which exists on behalf of interest proper, and not of premium. A return on capital which is not due to monopoly-privilege, but instead from opportunity costs, innovation, risk, or entrepreneurship, is what I understand to compose the majority of premium. In other words, I use interest as a term for unfair gains on capital, and premium as fair gains. Most don’t make this distinction, opting instead to call it all interest. For this reason, I am generally opposed to interest, but, more specifically, I oppose unfair interest, which is gained from monopoly (and which I believe to be the norm).

When people get wind of the fact that I oppose monetary interest in general, questions arise, the most common of which being “What is the incentive to loan without interest?” This is a very valid question indeed. What is the incentive of such an endeavor?

Opportunity Costs and Interest

Why would someone loan their capital to someone else, when they could do something with it themselves? This would be an opportunity cost!”

Indeed, many people like to argue that opportunity costs are the basis of interest, but I don’t believe this to be (entirely) so. At least, I don’t believe it to be so in regard to the mutualist definition of interest, which is a return above cost to monopolized capital. In other words, it is often believed that interest covers opportunity costs (meaning that one is paying for the inability of the lender to use their money for themselves), and in some forms of interest this may be true, but this is not the interest I oppose, but rather the “interest” I support, being fair and making up a small percentage of the total interest in the economy. The mass majority of interest is due, rather, to state-given privilege, either directly or indirectly. Since this portion far exceeds returns from opportunity costs, this is the portion I deem interest, while I believe the other, smaller portion, deserves a moniker of its own, which I have distinguished, at least for the time being, as premium.

It will be important to remember, throughout this essay, that the interest I oppose is a return to capital which is above cost. This depends on monopoly granted by the state. Premium is a return to capital which is determined by cost. This includes returns to entrepreneurs, who deal with unexpected matters that the market isn’t always prepared to deal with. As this essay moves forward, I will further clarify the form of “interest” that is valid, which I call premium, and the form of interest I am referring to when I condemn interest in general as a mutualist. Let’s first take an example for mutual reference:

Say you ask to borrow your friend’s car. You say, “Can I borrow your car? Mine will be out of the shop soon, and I’ll let you borrow it if or when you ever need to.” This seems like a fair exchange, but life circumstances get in the way: Your friend will be fined $10 if they don’t return their library book in an hour. This loss, if they were to loan you their car, is their opportunity cost of not keeping the car. Because you’ll make $70 or so at work, you offer to pay for the fee as well, covering the opportunity cost. Agreement is made, freeing the car for your use. Your debt to your friend, which can be written as an IOU if you like, is an equivalent use of your car and $10 for the fee, paid at a later moment.

Let’s look at what happened here. You were willing to pay the fee because the opportunity cost of not accepting was $60 in wages (because of missing work for $70, minus paying the $10 fee), and because your friend was otherwise unwilling to let you use their car due to their own opportunity cost of $10.

But, isn’t the $10 interest? Well, if we were defining interest as any return over that which is loaned, the $10 would be interest. This particular instance would be the “interest” I defend as premium, and not the interest I oppose, as it is governed by the cost principle. Remember, I am defining interest (in a negative sense) as a return on capital above opportunity costs.[4] In the example provided above, paying $10 on top of the use of the car is not a price above cost, because that is the highest apparent opportunity cost of the friend’s lack of having their car.

What keeps the friend from charging more than their opportunity costs, when the consumer’s opportunity costs are much higher? In other words, if a workday pays $70, and you are willing to pay $10 for your friend’s opportunity costs, so you don’t lose the other $60, what, other than good will, keeps your friend from charging more than the $10 opportunity cost? Why can’t they charge $30?

Price-gouging cannot occur under free conditions. In the existence of a free market in transportation, the prices asked are necessarily harmless, rising no higher than cost. In a free society, one could shop around for competitors or join a democratic association to reduce prices. If one is in need of a car, and asks a friend who needs $10 on top of equivalent usage of a car, in order to cover library late fees, one is likely to go ahead and call the next friend, and continue to do so, until they find one that is willing to offer use of their car at a lower price. Really, the only reason they should pay $10 on top of equivalent usage, is if all of their friends will face a similar late fee at the same time. This is unlikely. Therefore, the price of producers—in this case, friends with cars to use—is kept in check by way of competition. Prices under the proper conditions are forced down to cost. It’s unlikely that the $10 will be paid, let alone $30.

Just as it is true that competition can force the price of transportation down, it can also bring down the price of money. The only reason one would need to borrow a car from a friend is if they don’t have a working car themselves. If they had a working car, they would not need to get transportation from someone else, and thus face a potential premium. Likewise, if everyone had the ability to monetize their own labor, they would no longer have to borrow money from others. This would eliminate interest. Why would someone accept a loan at interest, when they have access to free credit?

Interest Never Monetized

It’s important to notice, from the prior example, that the opportunity costs, or premium, were accounted for in the credit, or IOU. Opportunity costs are the reason for writing the thing!

Opportunity costs are the basis of payment. It is because the grocer would rather be eating dinner with their friends and family—their opportunity cost—, than serving you, that you must pay them to serve you instead. Paying them offsets this cost. If not for this opportunity cost, and those similar, service would be free. This is important because many people argue that opportunity costs are the basis of interest, but the majority of interest is not due to opportunity costs.

Monetary opportunity costs earning a return is only valid in regard to independent investors, who have earned their money, and not of banks, who have simply monetized the labor of others. Even then, this is only true when everyone else has fair access to loans as well, which usually isn’t the case. The difference between interest on independent investments and interest on bank loans will be defined later on as being a difference of interest on money, and interest on monetization.[5]

If you accept the $10 fee for the use of your friend’s car, and write an IOU which includes this fee, the opportunity costs have been monetized. A proper money is a measure of such costs. This is, unfortunately, not how things are done today, when interest is charged. The nature of interest is that the money to pay it back is never created at all.

A conventional bank will loan you federal bank notes, depending on your credit or collateral, at interest. Not only is this interest a problem in itself— because it is an unfair return above cost, since the only thing backing that money is your own good will (credit score) or collateral—, it is an unfair return above cost that keeps growing, and which a large portion of the population are unable to pay, because it is never monetized.

It is only by loans with interest that the money makes it into the economy at all. When the banks loan money (100%) at interest (7%), and there is no other means to acquire the money (107%), there is necessarily a class of debtors created (7%), despite their effort. Their lack of ability to pay interest is not necessarily due to lack of virtue. Even so, this class of debtors may even be forced to accept debt upon debt, consolidating loans, just in order to more easily get out of the debt trap.

People are kept in perpetual debt, and people kept in perpetual debt must find employment by others, being unable to afford their own capital. This ensures that the ruling class, who have benefits from government privileges, and are able to earn money in an easier manner this way, are able to live off of the work of others.

The only reason we accept such an unjust system of banking is because the state does not allow us to create our own untaxed currencies, which would be capable of solving the problem, and because we must pay our taxes in federal notes. This ensures that everyone must essentially do what the state tells them. This will change with nothing short of civil disobedience.

Interest Upon Monetization

Before we continue, let’s make a distinction: We’ll make this distinction a) interest/premium on money, and b) interest/premium on monetization. What is the difference? For sake of this example, interest/premium on money is interest/premium attached to the good or service which money represents, or on money which was gained from another source, while interest/premium on monetization is attached to the service attributed to creating currency. Some call it seigniorage, but that word carries many contradictory connotations (I will be using seigniorage in both positive and negative senses, as you will see later on).[6] Take an example, for mutual reference:

You work a wage-job and save up $2,000. You really want to use your money alongside a trade-in for a newer car, which you expect to save you $100 in gas per month. However, you’ve just received wind that your friend was arrested, and their bond is $800. They are unable to pay it out of their own account. You visit them in jail, and they say they can pay you back the $800 in one month, plus $100 to make up for the gas you won’t be saving (your opportunity costs). According to some folks, you just earned $100 in interest. According to my view in “Interest and Premium,” you’ve just earned $100 in premium, my word to distinguish “fair interest.” The question, though, is what the source of this premium was. Was this premium on money, or premium on monetization? This (like the car example) was an example of premium on money. You have loaned your money, but had no hand in its creation, you earned it at your job. As Thomas H Greco, Jr. suggests,

Am I saying […] that all interest is dysfunctional and must be avoided? Not necessarily. It is one thing for those who have earned money to expect a return for its use when they lend or otherwise invest it; it is quite another for banks to charge interest on newly created money that they authorized based on debt. [iii]

So then, what is a return on monetization? Monetization is the act of deed or title-writing for the sake of exchange. This can be forgone (as in barter, vocal contract, or gift), done for oneself, or mediated by a third-party, such as a bank. When this action is forgone, or is done for one’s self, it is generally without a price at all, premium or otherwise. It is when a third party, such as a bank, enters the picture that we see the first signs of wages, premium, or interest paid upon monetization (money becomes necessary in all advanced market economies). A return on monetization is payment for creating money. A return on money is payment for money that is already created.

A return on monetization necessarily involves a third party, like a mutual credit association, which extends credit to a second party so they may make exchanges with the first. If a person comes to the association, having good credit, or substantial collateral, the association can fairly appraise the value of this, and can issue currency backed by it. A return on monetization would be any payment to the association for such an act. Some know this as seigniorage.

The act of monetization can extract interest, or it can keep payments at cost. Since the association is monetizing the good will or collateral of the person in question, and is extending money to them which is backed by their own value, the opportunity costs of such a loan are non-existent. In a free market, competition will force interest out of the picture, but, when the bank is allowed to maintain a monopoly, interest can be charged.

Measuring the Costs of Banking

The premium and interest (or seigniorage) on monetization, just as on money, can be established by analyzing costs. As stated before, it helps to have a third-party certify our money, in order that it will be willingly accepted by strangers in the same network. This third party certainly deserves pay for taking on the workload of banking. Is their payment interest? The portion that is fairly due to them is not the interest I oppose, but is instead wages or premium (if an entrepreneurial bank), that which I support. The line of demarcation here is at the cost of operation: Once a banker earns more than a proper competitive wage and their entrepreneurial premium (if existent)—that is, when they charge monopolistic prices above cost—, they begin to earn interest (in the negative sense).

The interest mutualists oppose is measurable. In regard to monetization, it is the difference that exists between cost and usury. The costs of creating money includes the price of printing paper or recording digital data, insurance or demurrage for losses, rent (if applicable) and utilities, security, etc. as well as the staff’s salary. These are all very measurable. It is when the bank’s income raises above these costs that interest (as the mutualist defines it), or unfair seigniorage, is being made by the bank. In the mutual bank, it is non-existent.

The only reason usurious banks can exist today is because of state-granted privilege, and private (instead of cooperative) ownership. If banking were competitive, mutual banks would offer the most competitive prices available, the most member influence, and would surely win out with free loans.[7] Of course, those who have better credit ratings, or more valuable collateral, should be able to make larger claims for credit, and receive larger loans.

One can see now that interest and premium on money is different from interest and premium on monetization, because of the nature of its acquisition. Returns from monetization imply returns from creating money, payment for making it. Returns from existing money imply that this money was gained in some form or fashion from another party. While both monetization and existing money are capable of gaining fair and unfair returns alike—premium or interest—, monetization exists at the macro level, and existing money is lent on the micro. For this reason, interest on money depends principally upon interest on monetization. Due to the scarcity of money at the level of monetization, those folks lucky enough to acquire money can lend it to those who cannot. For this reason, it is most necessary to attack interest at the point of monetization. This entails a deeper look into collateral and its assessment.

Collateral and Assessment

As monetization often depends on it, the topic of collateral and its value comes up. If money is printed based on collateral, this money must represent the value of the collateral at all times— no more, no less—, less inflation or deflation take place and destabilize the money’s worth.

When an abstract unit of measure is being used in the economy, which represents various goods and services, the supply and demand of the goods and services fluctuate in relation to one another.[8] To keep the value of money constant with the goods and services it represents, the standard must be allowed to float,[9] the goods and services must remain under constant assessment by way of spot-pricing, and the account of the holder must be adjusted accordingly. In other words, if the market value of the collateral used for a loan goes up, the owner of the collateral should be able to make a claim for more credit. If the value of the collateral goes down, the bank should have a claim for credit reduction. If this does not occur, interest is made possible on behalf of the collateral-owner or the bank, and monetary inflation and deflation become an issue. Another example:

Say you live in a free society. In order to make purchases there, in lieu of state money, you find a neutral third-party to certify and insure your transactions. You sign up for a line of credit, which must be paid back without interest. The loan is extended on your behalf according to the bank’s estimate of your current income and its level of security, and is further insured by your past credit history. It must be paid back according to the estimate of the income you’ll receive in the future. Another option is extending credit according to collateral’s (a mortgaged item) current value, to be paid back according to its future value (spot-price). So, if your labor or collateral becomes more valuable in the future, you pay more back for it. This fee is a form of negative seigniorage. If it becomes less valuable, you pay back less. This is a positive seigniorage. Here is how it works, beginning with the entrepreneur, and then into particular industries and further into the economy as a whole:

Say an individual, A, is the first one in the market with a product, x, and they want to use it as collateral for mutual credit. They agree to the spot-price of $100 (to keep things simple), the bank’s estimated value for two units of x, making a single unit worth $50. No interest is demanded. If the loan is not paid back, the bank will sell the items for a price of $50 a piece, but if it is paid back they will give the title or items back to be sold or used by individual A. Only upon spending the money does A actually go into real debt, and need to do work to claim their collateral back. Until they spend, or competition drives a change of value in collateral (creating negative or positive seigniorage), they hold the entire title to their collateral, all $100 with which to buy it back. This goes on for some time, with debits and credits. The product is a success, and is stable collateral at $100 (ideal situation, but using it for sake of simplistic demonstration of principles).

Another person, B, copies A’s idea upon seeing their success, and starts making the same product (there is no intellectual property protection outside of contract). Person B goes to the same bank and asks to use the product for collateral. Because demand remains consistent, a new person entering the market with the same product means a drop in value (because-value is largely determined by scarcity).[10] Person B does not mind that they won’t receive the entrepreneurial price, and is willing to settle for less. The value of the product, because of a new supply, has dropped to exactly half. The two producers, A and B, are at par with one another in productive capacity. The bank, under obligation of contract, has no choice but to offer a new spot-rate to person B. Instead of offering $100, as was done to entrepreneur A, $50 per two items is now offered to person B, and a $50 demurrage fee is applied to person A[11] (this is an extreme amount, but gets smaller as more people enter the market. If one more person would have entered the market, it would have been $33 1/3 instead. Most markets have multitudes of sellers, especially the more competitive markets). If demand would have increased, and the bank would have loaned $200 to person B instead, person A would have received a dividend of $100 to make up for their seigniorage adjustment. Why is this?

Seigniorage Rates

Person A was the first in the market, and supplied the whole market, so they had an uncompetitive price, and could get away with it because they were first and thought of the idea. For a time, they receive a higher price for their collateral. This is fair that they get such a premium, because they did the work of origination. The value of the goods when they entered was $50/unit and remained $50/unit until person B entered the market, adding to the supply, which dropped the value down to half. So, let’s look at the bank transactions. Person A got $100 for two units, and when person B enters the market, it drops the value, so person B gets a loan for half the original value, $50 (or $25/unit), and person A must pay back $50 in demurrage if they want to maintain title to their product. Each one’s products are valued the same, and the value of money remains consistent with the value of its basis. When the value of money is kept consistent with the value of its basis, in the manner described above, money floats at its clearance price.[12] If this did not occur, deflation and inflation of the money would occur.

Think about it, the above example keeps the value of money constant with its basis, but allows the value of goods to fluctuate. A product may drop from $50 to $25 a piece, but so long as the supply goes from two to four units the value of the supply as a whole remains the same, $100. The value of the individual product was reduced (but the physical amount was increased!), due to new supply, and the amount of money in the system was reduced with it relative to quantity (by way of not giving out the full loan of $100 to person B, and charging A demurrage). The values as wholes completely match, however. Had the product maintained constant value at $100/two units with B’s production, and were demand to rise at the same rate as the supply, the amount of money would have increased at exactly the same rate.

Say person B got the full loan for $100/two units of collateral (or $50/unit x 2) and spent it, but the consumers still only wanted to pay $100 total. Now, person A and B are both producing two units (total of four), and trying to sell them at $50 a unit to pay back their loans. That’s $200, but the consumers are only willing to spend $100! The producers have no choice but to reduce their prices or make fewer products, and thus fewer sales. The producer who is willing to drop their price and make more sales has the competitive edge, and thus makes the other conform to their new, low prices. So what has occurred with the money? There is only $100 in sales being made, so the currency has deflated and lost purchasing power. There is an extra $100 in the economy, with no backing in sale-rates. Money which cannot buy anything has no use, it is a loss of value to its holder, who had to work for, or trade collateral for, this item without value. Money representing products without demand must be recalled by way of demurrage fees.

Let’s say, instead, that the value of the collateral increases. In this instance, the bank owes more money to the holder of collateral. If this money is lacking, exchanges are hindered and the original supplier is ripped off. Say the items mentioned above retain their value of $25/unit, with two sellers in the market, but loans are given for $15/unit to two people, who produce two units each. The items are still worth $100 in total, or $25/unit, but there is only $60 in the economy representing them. If this $60 is dispersed evenly between the two people, they can only purchase one item each from each other (at $25), and have an extra $10 between them without redemptive value left over (since neither producer will let go of an item valued at $25 for $5), as well as two extra units which cannot be exchanged, due to a lack of means (money). This makes for a dysfunctional economy, where items are being produced which cannot be sold.

Obviously, two people in the same market have no interest in actually buying one anothers’ products; what we’re really talking about, though abstractly, is purchasing power in a more general sense. Instead of buying one anothers’ products, they would more properly monetize their products to buy products from other industries. This is where purchasing power really comes into play; I only use the example above to make the discussion of value more simplistic. This now being cleared up, I want to the discuss the various levels of demurrage needed in a healthy credit clearing network, which exists across industries.

Credit Clearing

Just as it is necessary to charge a demurrage to the entrepreneur, whose collateral has devalued with competition, or to pay them a dividend for its gain, it is also necessary to charge demurrage on, or pay dividends to, entire industries (or departments, or however much we decide to break down relationships), as their prices fluctuate in comparison to others. The firm must pay demurrage or receive dividends for fluctuations of prices within particular industries, but industries must pay demurrage or receive dividends for fluctuations of prices within the economy as a whole. If the value of gold were $3/grain, but decreased to $2 the next day for some reason or another, while both days carrots sell for $2/lb., the gold industry needs to pay $1/grain demurrage for their loss of value on the second day. If the next day it goes up in value again, the $1/grain will be returned as a dividend.

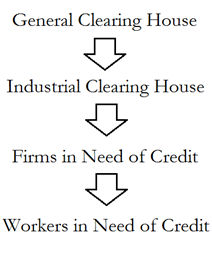

This may seem like a lot of calculating, and it is, but it can be rather decentralized. The best method I can think of is a credit clearing system in which clearing houses are organized by the firm, industry, and then by the entire economy, from the bottom up. One would sign up for a particular industry’s mutual credit, which adjusts seigniorage rates for entrepreneurs in the industry. This clearing house would be associated to the larger clearing house, which extends mutual credit to it and adjusts for the seigniorage of the collected industries, on behalf of the economy as a whole. The firms act in a similar manner for the workers, who ultimately receive the credit as wages or premium. This can really be broken into as many relationships as one sees fit. Some industries may demand departments of craft, some firms may demand committees, some committees may need subcommittees, etc.

At every level below the general clearing house and above the individual worker, mutual credit is extended from the level above to the one below it. General clearing will issue credit to entire industries. These industries must pay demurrage as values go down, or receive dividends as values go up on their collateral. These industries release the credit to firms. If the value of a firm’s collateral fluctuates, the industrial clearing house will charge a demurrage, or pay a dividend. If the value of an entire industry’s collateral fluctuates, the general clearing house will charge a demurrage or issue more credit, either of which are passed down through the industrial clearing house for collection or distribution.

If someone defaults on their loan, and their collateral cannot be sold by the bank at the expected price, any loss will be passed on to the sphere of the issuing sovereign in question— be it industry, department, firm, etc.—, by way of demurrage. Any collateral under the attendance of the bank will be subject to demurrage from entropy suffered. Some products may be unable to work as collateral, due to spoilage or quick loss. Those portable products used as collateral may be subject to a storage fee, while stationary items, such as buildings or warehouses full of goods, may be subject to inspection or insurance fees throughout the duration of the loan, and must issue warehouse receipts to the bank. In this way, the individual issues a specific title to their things to the bank in return for a generalized title to things in the economy.

Two Markets: Public and Private

My personal inclination is that housed or stored collateral loans may not always take place as often as direct-sales to the bank. Because of this, the bank may take on the role of public distributor and perhaps even public employer, where it will ask for prices equivalent to loans made, plus operation costs. Imagine a giant community-owned, non-profit, pawn shop, which is an analogy I have made in “Credit, Collateral, and Spot-Pricing.” Like a pawn shop, a mutual bank may make transactions that are permanent, whereby the bank becomes the owner of the collateral and gains the rights to sale; or those that are temporary, whereby the collateral is used for a temporary loan.

There are two forms of market under such a scenario: One can go to the public distributor, the bank, or to a private one, the individual firm or worker; one can receive credit directly or indirectly, by loan or sale (but either way, one needs to be a member of the bank).

The prices of the public and private markets will stabilize and adjust to one another by way of spot-pricing. If an entrepreneur feels they can get more by selling on the market than they will make by using their product as collateral or selling to the bank, they may do so, and, if they succeed in receiving a higher rate, the bank is influenced to raise its spot-price. If they feel they will get less by market sale, or it will be more hassle because of the public nature of the bank, they can check the appraisal of the bank. If the bank cannot sell the item for an equivalent price, demurrage is applied to the person or firm’s credit. The bank will constantly adjust its spot-prices to market standards. In the end, the public and private prices should even out, but this will be evened out by public and private market forces influencing one another’s equilibrium in their fluctuations.

Those who are particularly skilled, or are involved in work of a more artisanal nature, producing unique products, may be more interested in trying their luck in private markets, trying to receive credit from other folks, rather than directly from bank loan based on surveillance of past markets. Those who are involved in more menial tasks, perhaps manufacturing goods industrially in mass, may find themselves more prone to accept spot-pricing and to forgoing the efforts of marketing. What is important is that this be left to the free decision of the persons impacted.

Mutual banking supports all realms of economic relations, competitive or cooperative, and may itself be seen as a form of coopetition, wherein individuals cooperate (by way of shared banking institutions) in order to compete (by way of market relations). In this way, mutualism is a radically centrist ideology, supporting both a public and private sphere of life. In many ways, it is compatible with other centrist, antiauthoritarian, or populist “third-way” positions such as distributism, and concepts such as subsidiarity and sphere-sovereignty.

Semi-public institutions may spring from the structure and concerns of the mutual bank, such as insurance or welfare programs, so far as they are accepted by their membership according to their bank’s articles of association. Some programs, no doubt, will be accepted—those with common benefit, or in common agreement, to all—, while others will not. Such is the nature of consensus democracy, a reflection of the will of its membership.

Prospects for the Future

In the future, mutual credit-clearing and spot-pricing can be managed by computer algorithms. These algorithms could adjust according to organic inputs, such as prices offered or demanded by individuals, firms, or industries as a whole. Not only does this allow for the democratization of industry, it has immense potential for wage and task allocation in the firm.

Currently, cooperatives face a poor ability to fairly distribute tasks and income to their membership according to labor inputs. With a computer algorithm, successes and failures (according to needs of the firm or committee) can be logged as organic inputs and outputs, following the actual inputs and outputs of the individual, giving a job score. In an assembly line, inputs and outputs—job scores—can be easily adjusted according to simple unit production rates. That is, it can be logged according to the actual number of things produced (Jim produced 20 and Suz produced 23), being rather objective. Instead, service-based industries may decide to follow inputs/outputs of consumer satisfaction, letting the consumers rate them directly and more subjectively. The ultimate decision on matters of rating, however, belongs to its corresponding sphere of sovereignty (industry, firm, committee, etc.).

The computer algorithms would be used to generate job spot-pricing for a firm based on the individual’s rate of success. The ultimate goal would be to seek a clearance price, in some ways similar to Sperner’s lemma. People would be free to trade positions or not, according to their willingness to accept the spot-price offered for their work according to their job score. This may include a tier system, such as used by guilds, wherein some positions must be entered as an apprentice or as a similar initiate. Graduation from one tier to the next may depend on one’s job-score, rather than the arbitrary will of one’s master. This may even take the place of some, perhaps all, elections. Of course, if one doesn’t like the price offered for a job or task, they may always shop around, and it will always fluctuate according to supply and demand.

Imagine getting to work and signing in on a computer. Upon doing so, you click through a chart which lists the positions and their duties, the term length, as well as the price offered you for the work, based on your past success rate (relative to others), or job rating. You scroll through until you find a position you like at a spot pay-rate and term-length you can accept, and you sign up for the position. Demurrage and dividend of wages will apply as others accept or deny spot-prices offered and, therefore, shift equilibrium. It shifts until everyone is reasonably satisfied.

Conclusion

In an economy functioning on mutual credit, all prices are determined by cost. The interest I oppose becomes non-existent, but premiums may remain. When they do, they are monetized and able to be paid back. Since opportunity costs upon monetization do not exist, money is best issued into the economy freely, with associated charges only for the labor of banking. In order to keep money at cost, it is necessary to maintain a system of spot-pricing for collateral (goods, or, services) wherein seigniorage payments balance one another out (in an economy with steady demand which is growing in competition) or follow the contraction and expansion in line with the value of goods and services in the economy. That is, to keep its value constant, money should remain consistent with its basis, and a seigniorage fee or payment, which adjusts throughout the duration of the loan along with the fluctuations of supply and demand, should be applied. Money, put into perfect competition at this point, will reflect all costs, and the third-party lending of money at interest will become scarce, or, quite probably, non-existent. The interest I oppose will disappear, perhaps leaving very small and temporary premiums.

The best way for a system like this to be carried on is by a nested credit clearing system that is organized from the firm to the industry all the way to the general economy; but it should be broken down even further. Each tier will adjust its own debits and credits, dividends and demurrages. Interest will be nonexistent, followed by rent and profits.

This may lead to a dualistic marketplace which has elements that are both public and private. These two spheres of marketplace will constantly work toward equilibrium as the spot-prices of the public bank adjust to the prices of the private sphere, and vice-versa. No one will be restricted to one sphere or another, and all prices will be fair.

This leaves us prospects for the future where computer algorithms may follow organic inputs to ensure a stable, fair, and secure form of credit-money distribution, based on supply and demand. This may even take the place of some sloppier procedures for imbursement within cooperatives, and even their committees and subcommittees, wherein jobs and payment can be allocated according to current job-scores and the supply and demand, amongst all employees, for the work being done, ensuring a fair distribution of power and specialization.

Notes

[1] It is also given value by way of taxation, which is forced payment for “protection,” and is the reason we must ultimately accept the currency instead of alternatives. This tax burden was also responsible for much of the value of gold during the era it was used as an exclusive basis.

[2] To understand the generalization process and monetization of goods and services, I suggest a reading of “Credit, Collateral, and Spot-Pricing.”

[3] Still, for the time being, for sake of ease in understanding, and because the principle remains generally the same, we may use examples of personalized IOUs in this essay.

[4] This interest can stem from many places, but commonly starts with the monopolization and disequilibrium of money. This is often applied by way of debt which is not monetized, and is unable to be repaid, or which is issued against a person’s will. This is explored later on.

[5] A quick definition will suggest that interest on money is interest from money which is loaned by someone other than a bank, but interest on monetization is interest from money that is loaned by a bank. We’ll get there shortly.

[6] The definition on Investopedia defines seignioriage as,

“The difference between the value of money and the cost to produce it – in other words, the economic cost of producing a currency within a given economy or country. If the seigniorage is positive, then the government will make an economic profit; a negative seigniorage will result in an economic loss.”

[7] Free loans not because they don’t have to be paid back, but because there is no interest attached to them. The loan itself is free (but the service of the bank is not).

[8] By this I mean the following: If money is backed solely by a single product—we’ll use gold for sake of tradition—the value of the money remains constant so long as the ratio of money to gold stays the same. If a grain of gold is worth $3, for instance, so long as the bank issues $3 for every grain of gold deposited, the redemptive value of the money stays the same. However, once a second commodity enters the picture, the standard needs to enter a “float,” whereby the unit is made more abstract. If silver enters the picture, for instance, the marginal utilities of these commodities fluctuate in accordance with one another: Some days people may demand silver more than usual. If the standard is “fixed,” this creates a problem of scarcity and abundance.

[9] Meaning it has an abstract value, and is not redeemed in one item alone, but represents a percentage of the economy as a whole.

[10] Example: Say a person is selling bread to two friends, who don’t know anyone else who is baking bread, but who can get all the bread they need from their baking friend. Say the bread is sold at $5 a loaf, but cost of ingredients is only $2 a loaf, making a wage of $3/loaf for the entrepreneurial baker. Another friend hears about this, and decides to make bread as well. The amount of bread (supply) has doubled, but the amount the friends are willing to pay for bread (demand) has remained the same. Now each seller can only sell half the amount of bread as before, or must drop their prices. The first person tries to sell less bread at the same price, but the other person is willing to accept less. The first person has no choice but to lower their price and make more bread, or they will be unable to make any sales. The two friends now get twice as much bread for the same price. The value of bread has decreased, and it has become more abundant.

[11] This may seem unfair at first, but it is simply an uncomfortable part of reality that our things do not always maintain their value. Money, properly representing things, should reflect the value of those things absolutely. Anything else is an act of magic, and as enticing as magic is, attempting to live by its intentions is an attempt to dismiss reality. This is dangerous. I would love for entropy not to exist, but until this is possible, it must be accounted for in our economy.

[12] The clearance price is the price at which “everything must go.”

References

[i] Thomas H. Greco, Jr., 26.

[ii] Ibid., 25.

[iii] Ibid., 32.

Back to Article Index