Mutualism refers to a social movement and corresponding philosophy— as popularized by Pierre Proudhon— that is decidedly modernist in its original orientation, coming out of the Radical Enlightenment. In the name of postmodernism and cultural Marxism—found among the elites of university campuses—, however, mutualism’s modernist orientation has been downplayed, resulting in confusion (obscurantism), polarization (“Tuckerites” and “neo-Proudhonians”), and followed by reductionism (‘the real mutualism is “neo-Proudhonism”’). This essay argues for the revival of mutualism’s modernist elements, such as its pursuit of collective reason, utilizing the developmental model of Spiral Dynamics, Integral theory, art history, history of the philosophy of science, mutualist history, and ecological-evolutionary theory. In it, I display clearly mutualism’s modernist origins, its position in Spiral Dynamics, its similarity to Integral theory, relationship to Marxism and cultural Marxism, and its position on war, stratification, and sociocultural evolution, as well as matters having to do with the current cultural war. Essentially, I argue that postmodernism is largely irrelevant to mutualism, and that mutualists would do best to adopt a position supporting something more like integral remodern mutualism, which I am advocating as being appropriate to tier-two consciousness in Spiral Dynamics, and in light of insights also from ecological-evolutionary theory.

Part 1

Spiral Dynamics

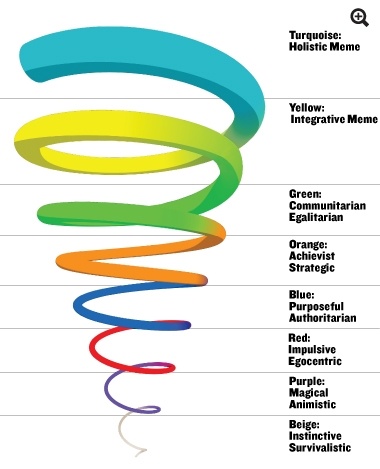

Spiral Dynamics refers to the developmental model created by Clare W. Graves and popularized by Don Beck. According to the Spiral Dynamics model, as promoted by Don Beck, individuals and their societies go through developmental processes through time that can be symbolized in the motion along a spiral (Don Beck holds that time itself is a spiral, which has both linear and cyclical elements). As one develops in life—either as an individual or as a society, and usually with some degree of both because societies are composed of individuals— one moves up the spiral along different levels, represented by different colors. These colors are Beige, as the base of the spiral, and going on up to Purple, Red, Blue, Orange, and then Green, a complete set representing the first “tier” of development. A second tier is composed of Yellow and Turquoise, with more colors expected to follow with continual development and research. One is said to move up the scale of colors as one develops a more matured worldview, each color representing a wordview orientation.

[Image source: https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/campaigns/the-big-rethink/the-big-rethink-part-10-spiral-dynamics-and-culture/8638840.article]

When one starts off one begins in Beige—the “archaic” self— which represents our most primal and narcissistic self. This self has very little concern for others, and is only really concerned with its immediate needs. The next step in the self is the “magical” self—represented by Purple— a self which is very superstitious and ritualistic, concerning itself mainly with security (often provided by supernatural sources). The Red self—the “dominator” self— is impulsive, and operates primarily on the principle of power and control. The “authoritarian” self—Blue—is concerned with formal rules and structured order. Next we have Orange—the “competitive” self—which is concerned with achievement and success. And lastly on tier one, we have the Green self—the “communal” self—which is concerned with equality of outcome. This concludes tier one.

As one develops as a person or as a society, one goes through these various stages from Beige, to Purple, to Red, and so on. One of the rules, however, is that stages cannot be skipped, but that one must go through the intermediate stage to get to the next level up. As one develops through the stages, one is understood to “transcend and include” the level below as one moves up, meaning that the previous levels never go anywhere, and are not eliminated in the individual or society, but are built upon as in a foundation, which can always be reverted to. In some ways, this model is not unlike Maslow’s Hierarchy of Human Needs (Maslow being a contemporary of Graves), which is a model suggesting that we develop further as our needs are met. In Spiral Dynamics, one cannot skip stages, but one can fall back down a stage or more, such that someone at a level Green development will revert to their old Orange or Blue or Red self. However, they are said never to forget that those later stages exist once they have experienced them.

The first tier represents different kinds of insights which, while being stacked, are incongruent and in competition with one another until one gets to the second tier. In other words, as one moves upward along the first tier of development, one tends to ignore the value of the previous stages, believing their new level of development to do away with the need for previous stages altogether. However, when one hits the second tier of development—starting in Yellow and going into Turquoise and beyond—one comes to understand that each of these stages of development has a function which is useful in the correct context.

These stages also coincide with different eras of humanity. Of particular interest to our discussion today will be the developmental stages from a medieval Blue to a modern Orange to postmodern Green and then an integral Yellow, which I argue should be filled by a remodern mutualism.

Premodernity, Modernity, and Postmodernity

The transition from premodern Blue to modern Orange was the change associated with the Enlightenment, particularly that part which was actualized in the form of the bourgeois or Moderate Enlightenment, and what resulted from it for the new WASP elite. The Moderate Enlightenment was associated largely with dualism, deism, and inductive science, and had followed after the mainline Scientific Revolution, the Moderate Reformation, and the Renaissance. It had— with aid from the proto-Industrial Revolution and the help of the resulting printing press, the allegiance of the lower gentry and bourgeoisie, the leadership of fraternal societies such as the Freemasons, and discussion networks and “third places” such as the Republic of Letters and coffee and tea houses— ushered in republican forms of governance and capitalist forms of economy. This was a massive achievement in the history of mankind, which had never before happened. The Orange Moderate Enlightenment is associated with the modern era, with separation of church and state, freedom of speech, republican government, and capitalism, to name a small number of its associated values. However, there is also a little told story about the Radical Enlightenment, which is of interest to us here.

The Radical Enlightenment tended to free thought, and especially grew out of the pantheism of thinkers such as Giordano Bruno, Baruch Spinoza, John Toland, and so on, but also with early atheists and agnostics, etc. Unlike the oligarchical republicanism supported by the Moderate Enlightenment deists, however, radicals tended to push for democratic republicanism and individualism. It’s actually with this bunch that the radical and socialist, Gustave Courbet, the leader in modernist art, would be at home, painting a fellow of interest to us in this discussion, the radical republican and mutualist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. Among the radicals, modernism considered the limitations of the Moderate Enlightenment from within Orange itself (and may actually be an anticipant of Yellow or Turquoise, ready before its time).

The Enlightenment produced many changes in art, which would come to be known as modern art, which—in its widest sense— would take the form of Romanticism, realism, naturalism, symbolism, impressionism, Fauvism, cubism, expressionism, cubism, photorealism, pop art, and more. Built into many of these movements following the Enlightenment, was the question of whether the Enlightenment was even living up to its own claims of progress. Romanticism, for instance, would push back against Enlightenment rationalism to some degree. Because of Romanticism’s anti-rationalism, and despite its being a form of modern art, it is sometimes considered counter-Enlightenment and anti-modern, and may not be the most suited to being described as a form of modernism, Orange. However, much within modern art challenged the Enlightenment, and Romanticism was not alone in this. But, where Romanticism criticized the Enlightenment for going too far in its quest of rationality—largely from a populist and aristocratic position—, modernism (in a wide sense which includes realism) challenged the Enlightenment to move further (though, perhaps with some spiritual guidance), some elements of which—such as the socialism of realist painter, Gustave Courbet— may be an outgrowth of the persistent Radical Enlightenment.[1] Naturally, Christopher L. C. E. Witcombe holds that

It is in the ideals of the Enlightenment that the roots of Modernism, and the new role of art and the artist, are to be found. Simply put, the overarching goal of Modernism, of modern art, has been the creation of a better society.[2]

Remodernist, Richard Bledsoe, says,

I define the era of Modern Art as running almost 100 years, bracketed by two art shows: the Salon des Refusés in Paris 1863, to the first major Pop Art show held in New York in 1962. The roots run deeper, and the influence lingers longer, but this is a useful measure for when Modern ideas were the most important in the culture.[3]

Important to note is that Gustave Courbet—who will be central to our discussion of modernism—was on the list for attendance at this event, though his painting of drunken priests was refused even here, and his fellow in the artists’ federation he put together, Manet, took the lead in modern art. Interestingly enough, Courbet’s piece The Painter’s Studio: a real allegory summing up seven years of my artistic and moral life, which was painted prior, is another contestant for the origins of modernism in art. On the left in this painting are people who Courbet associated with problematic elements in society—“the exploiters and exploited” as he put it, or “a cast of stock characters: a woodsman, the village idiot, a Jew, and others” as others put it[4]— while on the right are found people who Courbet is fond of, including his close friends, collectors of his art, and the mutualist Pierre Proudhon. We might also point out the relationship of modernism to avante-garde, a word which was first coined by the Saint Simonian, Olinde Rodrigues, in his essay “L’artiste, le savant et l’industriel.” Modernism is largely a variety of avant-garde.

[Image source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a4/Courbet_LAtelier_du_peintre.jpg]

[Image source: https://www.wikiart.org/en/gustave-courbet/portrait-of-pierre-joseph-proudhon-1865]

In the pursuit of a better society, art and philosophy constantly interact and feed on one another. For instance—and along with placing him also in his The Artist’s Studio—, the modern artist Gustave Courbet had painted a portrait and a family picture of the radical libertarian socialist, Pierre Proudhon, reflecting his shared political views with Proudhon. This was typical of a modernist outlook. P. Andrew Sandlin holds that

Modernism was committed to utopian visions: for instance, international communism or nationalistic Nazism or global democracy. We can create society as heaven on earth.[5]

[Image source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gustave_Courbet_(1819-1877)_Pierre-Joseph_Proudhon_en_zijn_kinderen_in_1853_-_Petit_Palais_Parijs_23-8-2017_16-48-24.JPG]

Modern art is related to modern philosophy. Nonetheless, and unlike with art, The Basics of Philosophy page on modernism says that

There is no specifically Modernist movement in Philosophy, but rather Modernism refers to a movement within the arts which had some influence over later philosophical thought. The later reaction against Modernism gave rise to the Post-Modernist movement both in the arts and in philosophy.

Enlightenment philosophy is modern philosophy, it turns out. And

Modernism was essentially conceived of as a rebellion against 19th Century academic and historicist traditions and against Victorian nationalism and cultural absolutism, on the grounds that the “traditional” forms of art, architecture, literature, religious faith, social organization and daily life (in a modern industrialized world) were becoming outdated. The movement was initially called “avant-garde”, descriptive of its attempt to overthrow some aspect of tradition or the status quo. The term “modernism” itself is derived from the Latin “modo”, meaning “just now”.

It called for the re-examination of every aspect of existence, from commerce to philosophy, with the goal of finding that which was “holding back” progress, and replacing it with new, progressive and better ways of reaching the same end. […]

Some Modernists saw themselves as part of a revolutionary culture that also included political revolution, while others rejected conventional politics as well as artistic conventions, believing that a revolution of political consciousness had greater importance than a change in actual political structures. [6]

In some respects, and while not all modern art movements—such as Romanticism— had supported the Enlightenment, modernism[7]— which perhaps first shows itself in the realism led by Gustave Courbet— had been a revival or continuation of the Radical Enlightenment mode of thinking to some extent. Courbet would question the extent to which the bourgeois Moderate Enlightenment brought about prosperity, as by depicting commoners in non-romanticized form. In true modernist form, Gustave says in his “Realist Manifesto,” demonstrating just how arbitrary distinctions in genres of art are, that

The title of Realist was thrust upon me just as the title of Romantic was imposed upon the men of 1830. Titles have never given a true idea of things: if it were otherwise, the works would be unnecessary.

Without expanding on the greater or lesser accuracy of a name which nobody, I should hope, can really be expected to understand, I will limit myself to a few words of elucidation in order to cut short the misunderstandings.

I have studied the art of the ancients and the art of the moderns, avoiding any preconceived system and without prejudice. I no longer wanted to imitate the one than to copy the other; nor, furthermore, was it my intention to attain the trivial goal of “art for art’s sake”. No! I simply wanted to draw forth, from a complete acquaintance with tradition, the reasoned and independent consciousness of my own individuality.

To know in order to do, that was my idea. To be in a position to translate the customs, the ideas, the appearance of my time, according to my own estimation; to be not only a painter, but a man as well; in short, to create living art – this is my goal.

Courbet stands out as one of the most important painters of the modern period, and greatly exemplifies the period of modernist art. By some estimations, modernist art started at the Salon des Refusés, in which Courbet was on the list to be featured (but his painting of priests was banned), but this is probably a little late considering avant-garde and some of Courbet’s prior works (among others). Of modernism, Christopher L. C. E. Witcombe says that,

As we have seen, it was the 18th-century belief that only the enlightened mind can find truth; both enlightenment and truth were discovered through the application of reason to knowledge, a process that also created new knowledge. The individual acquired knowledge and at the same time the means to discover truth in it through proper education and instruction.

Cleansed of the corruptions of religious and political ideology by open-minded reason, education brings us the truth, or shows us how to reach the truth. Education enlightens us and makes us better people. Educated, enlightened people will form the foundations of the new society, a society which they will create through their own efforts.

Until recently, this concept of the role of education has remained fundamental to western modernist thinking.[8]

But, alas—as with the Radical Enlightenment—, all good things must come to an end. The modern era came under attack with postmodern Green. According to one perspective,

By the time Modernism had become so institutionalized and mainstream that it was considered “post avant-garde”, indicating that it had lost its power as a revolutionary movement, it generated in turn its own reaction, known as Post-Modernism, which was both a response to Modernism and a rediscovery of the value of older forms of art. Modernism remains much more a movement in the arts than in philosophy, although Post-Modernism has a specifically philosophical aspect in addition to the artistic one.[9]

Nonetheless, as one person puts it, postmodernism isn’t something that stands on its own, but is actually modernism turning upon itself:

Postmodernism is really hyper-modernism’s attack on its predecessor. Modernism birthed postmodernism, and then postmodernism committed patricide. Or, to alter the metaphor, it’s the case of the snake devouring its own tail.[10]

Along with the postmodern attack on modernism, Modernism-proper would be infiltrated and financed by the CIA.[11] Much of this was due to an apparent concern (during the Cold War) about the prominence of economic Marxism among Modernists (the early modernists, like Courbet, and unlike many Modernists, were not Marxists).

Whereas modernism was trying to achieve a better society—whether Marxist, nationalist, objectivist, mutualist, or whatever—, postmodernism would reject these attempts in favor of a kind of egotistical narcissism. Sandlin speaks of this change as an adoption of “emanicipatory individualism:”

Postmodernism shifted from utopian society to emancipatory individualism. That is, the important thing was not so much a social vision as an individual vision, which society should guarantee. Society should guarantee that I can create my own reality. I am a producer and consumer of reality. An endless supply of options should constantly be available to me. I can be married or unmarried, homosexual or heterosexual, introverted or extroverted, passive or aggressive. I can be anything I want to be, and if for some reason I cannot, someone else is at fault. I am entitled to a multitude of options.

In all of its bizarre, tradition-crushing program, Modernism had maintained a unified theory of the triumph of reason, progress by constant, unremitting improvement. Postmodernism depicts life as fragmentary, chaotic, balkanized. There are no universals, only particulars: particular people, particular institutions, and particular communities.

If you think about it, this last part sounds a lot like original conservatism. The original conservatives like Edmund Burke opposed the French Revolution and Enlightenment because they tended to uproot individuals and their family and cultures in favor of a universal, cosmopolitan, global viewpoint. After all, the Enlightenment wanted to level everything before universal human reason. The postmodernist saw what happened with universal reason and the quest for utopia that it spawned. They identified Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Russia with Enlightenment totalitarianism. The problem with a shared vision of the good life is that people disagree on what the good life is. So the only answer is to retreat completely to the individual. In this, postmodernism is the child of Existentialism. And like the Romantics, the individual is the self-creator.

The postmodernists are anti-conservative anti-collectivists. This might sound contradictory to us. When we think of conservatives, what immediately comes to mind is their strong sense of individualism in the face of the collectivism of, for example, communism or fascism. The American Founding was largely individualistic. This is a tenet of what we call classical liberalism. The true conservatives stand for individual liberty against the collective.

So it might seem odd that postmodernists could be anti-collectivist. They are, in fact, radical, left-wing individualists. This is a way of thinking that some modern conservatives have never encountered. They assume that if we oppose collectivism, or statism, for example, we will have a better society. But that is far from the truth. Postmodernists want radical individual freedom from authority, freedom from morality, freedom from creation, from almost all of constraints. All they need the state for is to guarantee that freedom. (This, by the way, is how postmodernism intersects with Cultural Marxism.)[12]

Postmodernism did bring about some positive changes, but the extent to which modernism had the basic elements of this covered already, and in a healthy, solutions-oriented manner, is fairly arguable. Postmodernism would continue with modernism’s skepticism toward the present perfection of society, and extended it into a pessimism that society could ever achieve the sorts of values it sought to establish.

Postmodernism—Green— developed, like Romanticism, out of the continental counter-Enlightenment, which was itself a reaction to, and in ways an outgrowth of, the Moderate Enlightenment. Those among the aristocracy would express the counter-Enlightenment in terms of idealism, Romanticism, and symbolism, while others would eventually take to postmodernism, which rejected the idea that truth was actually attainable in any meaningful way. Some of these ideas were already unfortunately present in Modernism. Romanticism and idealism tended toward a degree of irrationalism, but they had not fully rejected truth or reality. Postmodernism would go so far as to reject the validity of these concepts. The Romantics sought to assert their emotions and aspirations, but the postmodernists merely wanted to criticize. In the case that postmodernists go about constructing anything, this is not what defines them as postmodernists.

The Problem of Postmodernity (Green)

We are currently living in the postmodern era, an era in which Green values have come to the fore and established themselves as dominant. Ken Wilber says that, “’Green’ refers to the basic stage of human growth and development known to various developmental models […] as ‘postmodern.’”[13] He says,

Beginning in the 1960s, green first began to emerge as a major cultural force, and it soon bypassed orange ([…]in short, “modern” in contrast to green’s “postmodern”) as the dominant leading-edge. Green started with a series of by-and-large healthy and very appropriate (and evolutionarily positive) forms […] and—centrally— both the understanding of the crucial role of “context” in any knowledge claims and the desire to be as “inclusive” as possible. […]

But as the decades unfolded, green increasingly began veering into extreme, maladroit, dysfunctional, even clearly unhealthy forms. Its broad-minded pluralism slipped into a rampant and runaway relativism (collapsing into nihilism), as the notion that all truth is contextualized (or gains meaning from its cultural context) slid into the notion that there is no real universal truth at all, only shifting cultural interpretations (which eventually slid into a widespread narcissism). […] If there were one line that summarizes the message of virtually all of the truly prominent postmodern writers (Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, Jean-François Lyotard, Pierre Bourdieu, Jacques Lacan, Paul de Man, Stanley Fish, etc.), it is that “there is no truth.” Truth, rather, was a social construction, and what anybody actually called “truth” was simply what some culture somewhere had managed to convince its members was truth; but there was no actually existing, given, real thing called “truth” that is simply sitting around awaiting discovery, any more than there is a single universally correct hem length that it is clothes designers’ job to discover.

Even science itself was held to be no more true than poetry (Seriously). There simply was no difference between fact and fiction, news and novels, data and fantasies. In short, there was “no truth” anywhere.[14]

Wilber refers to the resulting conflicts of postmodern society as “the culture wars.” He has also criticized postmodernism—despite his original praise toward it in A Brief History of Everything, and echoing other scholars— for its “performative contradictions,” such as its absolutist and universalistic claims about relativism and pluralism.

In some respects, postmodernism had been philosophically anticipated by other forms of subjectivism, such as in some aspects of skepticism and the marginal revolution (which was a break from the more objective labor theory of value), but especially in continental philosophy, such as nihilism, existentialism, absurdism, egoism, Marxism, and so on. Because of its relationship to other continental philosophies, it has been confused for having origins in Romanticism, idealism, and even thinkers such as Hegel or in Proudhon. But it had differentiated itself from these late modern philosophies and philosophers, even from Marx, perhaps originating firstly as a manner of art, and later as a philosophical approach (with Nietzsche being a possible exception or anticipant). In philosophy, postmodernism would express itself as postmodernism, as poststructuralism, as deconstruction, and critical theory, some of these coming under the common header of “cultural Marxism” or “neo-Marxism,” and becoming prominent influences on social sciences and especially Language, Literature, and Cultural Studies courses. A “revolt of the elites” would see cultural Marxism establish itself as the go-to ideology of professionals and management.

As the story goes, after the two World Wars, the world was a different, melancholic place, in which an existential crisis had to be faced head-on. The Wars had shaken trust in Enlightenment values, humanism, universalism, objectivity, and basically anything that can lead up to a shared worldview between human beings. With it, and also following McCarthyism, came a decrease in organized labor, and an increase in Civil Rights issues, including a movement against racial segregation, a second and third and now fourth wave of feminism, and so on. Philosophical expositions of the postmodern condition—basically repeating the angst found in the existentialist, absurdist, and nihilist philosophies of an earlier time, and much of modernism— came to the fore with postmodernism, poststructuralism, deconstructionism, critical theory, and so on, and was commonly found in Beat poetry and in other postmodern arts, and finally working its way into Cultural Studies departments. Postmodern philosophies stressed the inherent limitations of human beings to establish, grasp, or wield meaning, values, purpose, and so on. Rather than offering much substance of its own, postmodernism has been defined by its reaction to modernity and modern philosophy, in particular the Enlightenment, which it tends to despise.

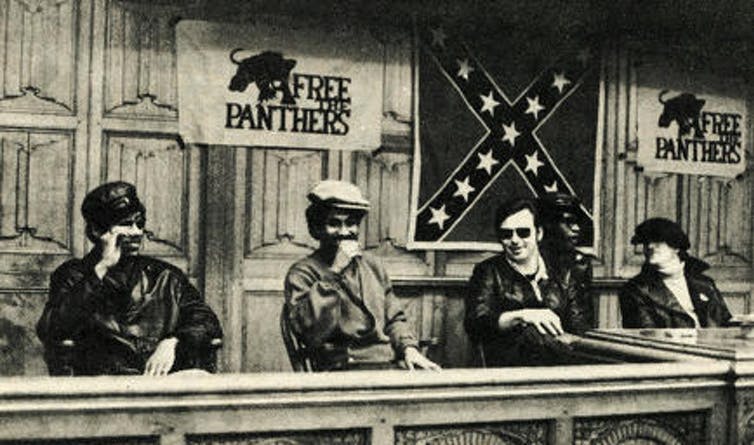

One important institution, which is often seen as being largely responsible for postmodernism, is the Frankfurt School, associated with Adorno, Horkheimer, Marcuse, and Fromm. Many of the postmodernists being Marxists who came to question the historical narrative of Marx, these Frankfurt thinkers, along with other such as Gramsci and Derrida, would come to be known as cultural Marxists in contrast to the economic Marxism of what would now be known as the Old Left. This cultural Marxism would take the dominant place of Marxism among the Left and establish itself as the ideology of the emerging New Left. The New Left would come to substitute cultural matters for economic ones, stressing identity politics and intersectionality, political correctness, and ending war over working class unity. The New Left would become prominent among many of the Hippies—themselves having developed from the Beatniks—and related groups such as the Yippies. A cultural revolution had taken place, and some among the New Left would buy in to the system, bringing some of their postmodern Marxist and hippie values along with them. Through this “revolt of the elites,” they would become the American New Class, an upper-middle class of professionals with tremendous sway on politics. They’d take a mature form in their position as Bobos (bohemian bourgeois), and secure their place in the technological race as the techno-managerial class. All of this would pose a great threat to more traditional, private capitalism, substituting corporatism and the therapeutic welfare and nanny state, and displacing many of the old guard, WASP (White, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant) male conservatives, as much of the New Class would now be composed of people of color, Jews, women, sexual deviants and more (though Christian-born white males still play a prominent role). Today, there is much conflict between the old guard, old-monied WASP elites and the new-monied Bobos, and they are in competition with one another for power. It’s Christian Nationalism vs. cultural Marxism. Nonetheless, they recognize a common need to keep their class interests up (such as when lesbian Bobo actress “Ellen” made clear that her politics did not separate her from her class interests with former president George W. Bush).

Political Jiu-Jitsu

The problem of postmodernism can be understood as a political Jiu-Jitsu act, in which the momentum of the Enlightenment, and in particular modernism (that is, at least to some extent, Radical Enlightenment) is used against it. In Jiu-Jitsu, the goal is not to use one’s own energy to defeat one’s opponent, but to capture their energy in order to steer them off course, thereby defeating them. Yuri Bezmenov, a defector of the KGB, tells of international cold warfare use of psychological operations and active measures in which Marxist ideology is administered to the United States public in an act of political Jiu-Jitsu. This is used to demoralize the American public to such a point that Yuri says that “exposure to true information no longer matters” to someone who has been infected. Realpolitik plays a major role in postmodern politics.[15]

[Full version here: https://youtu.be/jFfrWKHB1Gc]

Postmodernism did this with the scientific induction behind the bourgeois Enlightenment, particularly after the rise of modernism, leading to solipsistic outlooks and moral relativism that was also fueled by degrees of historicism. This is part of its being an outgrowth of modernism, which approached the limits of scientific understanding.

The sort of induction used by the Moderate Enlightenment was criticized by those among the Radical Enlightenment, because it was not sufficiently holistic. These thinkers believed induction coupled with reduction to be problematic, because it was only capable of taking things apart. It was deduction and intuition that put things together. Yet, the new Newtonian reductionism upheld by the bourgeoisie became the standard. Margaret C. Jacob contrasts the Newtonian deism of the Moderate Enlightenment with the pantheism of the radicals and Radical Enlightenment. She writes,

[T]here was a vast difference between the social assumptions held by pantheistic heretics who believed that God or spirit dwelt in nature, that in effect nature contained within it sufficient explanations of its various phenomena, and the assumptions held by essentially orthodox Newtonians, among them even Voltaire, who argued that God controlled nature from outside, as it were by laws and spiritual agencies.[16]

She says,

[T]he version of the mechanical philosophy that most captivated European thinkers, namely the Newtonian, argued in the strongest possible terms for a material order that was moved by spiritual forces outside of matter, by a providential creator who maintained a system of spiritual forces that regulates and controlled nature. If European radicals were to keep the new science and to escape its ideological burdens, then pantheistic and materialistic explanations would have to be fashioned. Yet these would have to exist in harmony with the mechanical world picture and the new scientific discoveries.

Enlightenment radicals searched for their philosophical foundations in two intellectual traditions. They embraced aspects of the new science while attempting to salvage and to revitalize purely naturalistic explanations of the universe that had largely flourished during the late Renaissance. [17]

Before the Newtonian Moderate Enlightenment, science carried a different meaning, but the bourgeois revolutions would eventually solidify induction as the foundation of the new science. As Larry Gambone writes,

By [the 1870’s] the term “Science” began to change meaning. Previously, any organized body of knowledge was considered a science and there was nothing smacking of pretentiousness or scientism in speaking about the “science of cookery” or “scientific socialism”. With the rise of Positivism and materialism came a new and more restricted use of the word. The term “science” was now reduced to those areas of inquiry which applied the methodology of the natural sciences. Positivism engaged in a search for the immutable laws of nature which supposedly existed independently of the observer. Any other approach was deemed unscientific or pseudo-science and condemned in language similar to that used by 16th Century heresy-hunters. Science had become a new absolutism and a new superstition.[18]

But much of the new science was based on a misunderstanding of Roger Bacon, who had gotten the idea from Sufis after the Islamic Golden Age. Idries Shah, Grand Sheikh of the Sufis, points out that the efforts to move science in the direction of induction and experimentation was a misunderstanding of the original attempt provided by these Sufis. He says,

It is interesting to note the difference between science as we know it today, and as it was seen by one of its pioneers. Roger Bacon, considered to be the wonder of the middle ages and one of humanity’s greatest thinkers, was the pioneer of the method of knowledge gained through experience. This Franciscan monk learned from the Sufis of the illuminist school that there is a difference between the collection of information and the knowing of things through actual experiment.

[…]

Modern science, however, instead of accepting the idea that experience was necessary in all branches of human thought, took the word in its sense of “experiment,” in which the experimenter remained as far as possible outside the experience.

From the Sufi point of view, therefore, Bacon […] both launched modern science and also transmitted only a portion of the wisdom upon which it could have been based.[19]

The new science, based on the misunderstanding of Roger Bacon’s followers, nonetheless, became the dominant worldview over time. Antonella Vannini describes a similar misunderstanding on behalf of another Bacon, Francis:

In the same years during which Galileo was working on his ingenious experiments, Francis Bacon (1561-1626) was arriving at the formulation of the inductive method, deriving general conclusions from the observation of the experimental method. He became one of the major assertors of experimental methodology, courageously attacking the traditional schools of thought which were based on Aristotelian deductive logic. The Aristotelian method, starting from general laws, or postulates, deducts empirical consequences which have to be proved; Bacon’s inductive method starts from empirical evidence to arrive at general laws. In order to produce objective knowledge, Galileo’s and Bacon’s scientific methods separated the observer from the observed. This approach totally transformed the nature and purpose of science. Whereas previously the purpose of science had been to understand nature and life, science’s purpose now involved the controlling and manipulating of nature. As Bacon said: “Objective knowledge will give command over nature, medicine, mechanical forces, and all other aspects of the universe”. In this perspective, the aim of science becomes that of enslaving nature, of using torture to extract its secrets. We are now far away from the concept of “Mother Earth”, and this concept will be totally lost when the organic concept of nature will be replaced by the mechanical concept of the world, which can be traced back to the works of Newton and Descartes.[20]

The inductive-reductionism of the Newtonian worldview was associated more with the bourgeois science of the Moderate Enlightenment than it was understood to be science among the more popular Radical Enlightenment. The Radical Enlightenment thinkers had taken more to the likes of Pyrrhonist skepticism or Sufi understanding of direct experience (perhaps owing to the asceticism of their own lay religious leaders, a practice that was shared between both radical Christians and wandering Sufis). The Sufis would make a particularly strong impact in what is now Spain.

When postmodernists attack modernism, they are openly attacking the Moderate Enlightenment, but also modernism, which may be a remnant of the Radical Enlightenment, and Modernism-proper (which was already losing sight of the original goals of modernism). Nonetheless, the Radical Enlightenment, due to its unactualized potential, is impossible to be “post” in relation to: radical modernity isn’t yet a thing. Yet, at the same time, the postmodern attack on the Moderate Enlightenment takes its problem of induction to a new extreme, perhaps in an effort of “political Jiu-Jitsu,” and this attack does not apply with as much validity to the Radical Enlightenment, though it attempts to treat both Enlightenments with one brush.

The difference between postmodernism and Modernism is actually one of degree rather than being a strict difference. Postmodernism is Modernism taken to reductio ad absurdum, and quite possibly as part of a conscious effort on behalf of some of its popularizers. Postmodernism, I repeat, takes the induction and reduction of the Newtonian Moderate Enlightenment and blows it out of proportion—suggesting that quantum theory and free will makes things unknowable—, rending it a vice instead of a virtue. This seems odd, as postmodernism is against claims of scientific objectivity. But, because it takes what Modernism presented and blew it out of proportion— for instance, the cultural relativity found in anthropology or the relativity and quantum dynamics of modern physics—we can understand postmodernism as taking induction too far. In many ways, these inductive sciences would orient the Modern world in a situation of relativity and subjectivity that postmodernism would take to an extreme.

There are some aesthetic similarities between postmodernism and Radical Enlightenment that need to be taken into account. The Radical Enlightenment did make a fair use of subjectivism, skepticism and apophathic thinking (that can be mistaken for poststructuralism), maintained its own questions regarding the limitations of reason, and was also critical of the bourgeois Moderate Enlightenment. It, for instance, would occasionally make us of Pyrrhonist zeteticism and of Sufi mysticism, and stood for radical republicanism as opposed to the oligarchical republicanism of, say, the American founding fathers. But these philosophies did not denounce deduction, deny reductive truths, nor assume infallibility. Rather, they provided a foundation upon which skeptical and free thinking individuals could approach the world with agency, making use of logic and reason all along the way, without becoming rigid in one’s views. Pyrrhonism, for instance, might suggest that one might remain pragmatic in action, and that while truth is never 100% certain, it is more problematic not to act on suspected truths than to act imperfectly. This contrasts to the postmodern position, which serves to deflate confidence. Similarly, Sufi illuminism maintained that there were limits to reason, which the postmodernists certainly echo, but were nonetheless advocates of using intuition in a way that is too assertive to be postmodern, and which nonetheless supported the use of logic. Many radicals were critical of modernism themselves, so we must not get confused about the nuance between the radicals and the postmodernists. The problem with postmodernism is not that it criticizes, or that what it says is incorrect, necessarily, but that it serves to make a person indecisive and non-assertive, weak, by orienting the individual in negation, rather than providing the individual the tool of negation in compliment to position. Pragmatism is a much better philosophy for radicals than postmodernism, and in fact grew out of John Stuart Mill’s radicalism. Proudhon, too, is considered to have been a pragmatist by many accounts.

Because of postmodernism’s pessimism toward truth, meaning, purpose, and other classical ideas—and to the Enlightenment and Western society at large— it has been unable to establish itself as a real powerhouse in the manner of the old WASP elite. Nonetheless, it is supposed by some scholars that the role postmodernism—and, in particular cultural Marxism— is supposed to play is that of a virus in Western culture. In this case, it is not correct to expect it to do much else but eliminate the host. It is suggested that there are other value systems—non-Western value systems—that can fill the vacuum left in the demise of Western culture. By some of these outlooks, much of the culture war exists between national and international capitalists, with postmodernism as an attack on nationalistic capitalists by international capitalists, or between industrialists and bankers. WASP culture and cultural Marxism compose the antinomies of postmodern U.S. society.

Part 2

Remodernism

While postmodernism is often said to have really taken off and become the standard theme of the era after the World Wars, its proper beginning was as an art movement that came out of the late 19th century. This art movement would lend its name to the era that would become known as postmodern, and to the poetic and philosophical approaches that would follow in the Beatniks and among the cultural Marxists. Like postmodernism and its reaction to modernity, remodernism has its origins as an art movement, and is a direct reaction against postmodernity. According to one remodernist, “The Postmodern Establishment is trying to switch off the Enlightenment.”[21] This, much to the horror of modernists, who see the job of the Enlightenment as unfinished business. Richard Bledsoe says

Modern art can be observed as a series of trends proposed as solutions to the void introduced into heart of art-and by extension, life itself. Nothing seemed to work for long.

This lead to a terrible burnout, and what we have now: the sophistry, shallowness and will to power of the Post Modern age. But even this horror is coming to an end. We are at the beginning of a new era. Welcome to the Remodern Age. We integrate the fragmentation of the Moderns back into a holistic approach, art as a tool for communion and connection once again.[22]

Remodernism was established and defined in a manifesto by Billy Childish, and it is best to quote the man himself on the relevant parts of remodernism to political philosophy. Billy says that “Modernism has never fulfilled its potential.” So, “Remodernism takes the original principles of Modernism and reapplies them”. Childish says that “Remodernism discards and replaces Post-Modernism because of its failure to answer or address any important issues of being a human being.” He says that, instead, “Remodernism embodies spiritual depth and meaning and brings to an end an age of scientific materialism, nihilism and spiritual bankruptcy.” On point, he suggests that “We don’t need more dull, boring, brainless destruction of convention, what we need is not new, but perennial.” In conclusion, and displaying clearly the intentions of remodernism in art, Billy Childish remarks that

It is quite clear to anyone of an uncluttered mental disposition that what is now put forward, quite seriously, as art by the ruling elite, is proof that a seemingly rational development of a body of ideas has gone seriously awry. The principles on which Modernism was based are sound, but the conclusions that have now been reached from it are preposterous.

We address this lack of meaning

Rather than the elitism of the postmodernists, Billy says that “Remodernism is inclusive rather than exclusive”. Another remodern artist, Richard Bledsoe, in the description for his book Remodern America, says that

Art reminds us of who we are, and shows what we can be. But the visual arts are undergoing a crisis of relevance. Elitists have weaponized art into an assault on the foundations of our culture.

Don’t concede the vital experience of the arts to deranged partisans. Art is a more enduring and vital human experience than the power games of a greedy and fraudulent ruling class. The story of the 21st Century will be the dismantling of centralized power. As always, this course of history was prophesied by artists–those who are intuitively aware of the path unfolding ahead. Their works become maps so that others may find the way. Enduring changes start in the arts.[23]

Remodernism stands opposed to New Class, Bobo (Bohemian Bourgeoisie) elitism, to jargon-filled babble that can’t be understood in common terms or upon earnest explanation, to political correctness, to nihilism and materialism, and to negation without solution: In short, to postmodernism.

Billy Childish doesn’t explicitly state so, but I believe it is fair to suggest that the roots of remodernism, like that of the original modernism, lie in the Radical Enlightenment.[24] My reason for suggesting this is that the unfulfilled potential in the Enlightenment has its home here, rather than in the Moderate Enlightenment, which actualized its potential in modern society. As such, remodernism makes perfect sense for a second tier (Yellow/Turquoise) worldview, and is the most reasonable backdrop for integral mutualism.

Integral

Integral is an approach created by Ken Wilber, which is an attempt to map the various approaches to knowledge in four quadrants of orientation: internal or external, individual or collective. These mix to form the four quadrants: individual/internal, individual/external, collective/internal, collective/external. Ken Wilber suggests that internal affairs of the individual include subjective matters such as psychology, whereas those external to the individual may have more to do with psychiatry; and those internal affairs of the collective might include the subjective meaning behind its myths, whereas its external affairs might be regarded in its social structures. Subjective is basically another way to understand internal, and objective a way to understand external understanding. The whole range of human knowledge—from physics to biology to theology to mythology— is said to be able to fit into the four quadrants. It’s understood that what brings these quadrants together—what unites them—is their being aspects of a holon, a whole composed of parts which is also itself a part of a greater whole.

Wilber refers to holarchy as the hierarchical relationship between greater and lesser holons, such as particles and atoms. He distinguishes this natural form of hierarchy from what he calls dominator hierarchies, in which a holon will try to establish itself as dominator of holons of a similar level (say cells) and stand in as a representation of the whole. Ken Wilber uses the example of a cancer for this sort of dominator hierarchy, which is clearly an unsustainable relationship. For Ken Wilber, “greater” and “lesser” holons are in reference to collectives and individuals, not individuals and individuals or collectives and collectives of a similar sort. For an individual or collective to attempt to be “greater”— in any significance to Integral— may represent an attempt to form an unsustainable dominator hierarchy.

Integral holds that lesser holons are understood to have more breadth and to be more fundamental, while greater holons are understood to have greater depth and to be more significant. Wilber suggests that neither are better or worse than another in any ultimate sense. He says that more fundamental holons (like particles to the atom) are always greater in number than more significant holons (like atoms to particles), and can be destroyed by destroying their fundamental parts, while the fundamental parts can remain in absence of their more significant holon. Ken Wilber provides an example of evolution producing greater depth and less breadth, or span, in his book, A Brief History of Everything.

There are fewer organisms than cells; there are fewer cells than molecules; there are fewer molecules than atoms; there are fewer atoms than quarks. Each has greater depth but less span.

The reason, of course, is that because the higher transcends and includes the lower, there will always be less of the higher and more of the lower, and there are no exceptions. No matter how many cells there are in the universe, there will always be more molecules. No matter how many molecules in the universe, there will always be more atoms. No matter how many atoms, there will always be more quarks.

So the greater depth always has less span than its predecessor. The individual holon has more and more depth, but the collective gets smaller and smaller […][25]

In Spiral Dynamics Integral, the form which unites Spiral Dynamics with Integral, it is understood that as one moves up the developmental spiral, one develops a more expansive worldview, in which one is oriented in greater and greater holons. Then, when one makes the “leap” from tier one to tier two, one establishes a more integral understanding, starting in Yellow, in which all of the different colors are acknowledged and integrated in a compatibilistic whole, rather than competing with one another. This means also that one begins to see the compatibility between the internal and external understandings of the individual and the collective. Whereas before, as one stepped into Green they rejected Orange, when one steps into Yellow or Turquoise one has an understanding of how Green and Orange can coexist to one another’s benefit. This does not occur until tier two consciousness.

Mutualism, an Integral Solution for Remodern Times

Mutualism is a social movement and corresponding socioeconomic worldview arising out of the Radical Enlightenment, and my candidate for second tier (Yellow/Turquoise). This worldview is historically expressed most explicitly in the works of Pierre Proudhon (the mutualist painted by Gustave Courbet), who was among the first to popularize it. Mutualism is an ideal candidate for a second-tier worldview in Spiral Dynamics Integral, as mutualism has traditionally integrated various different positions (such as market competition and socialism) into a compatibilistic outlook. Its more individualistic approaches may resonate with a Yellow worldview, while its collectivistic tendencies may express Turquoise, but both sides are honored and remain intact. This worldview expresses a simultaneous desire for individual freedom and social equality. It ultimately aims to balance freedom and equality in a project of—the seemingly oxymoronic— libertarian socialism.

Anticipating Spiral Dynamics, which describes something quite similar, Proudhon—the heavy-hitter of mutualist philosophy— remarks that “Society, in virtue of man’s capacity to reason analytically, oscillates and deviates continually to the right and to the left of the line of progress, according to the diversity of the passions which serve society as motors for action.”[26] For Proudhon, “Justice is the central star which governs societies, the pole about which the political world turns, the principle and the rule of all transactions.”[27] Another star—the Blazing Star— is spoken of by another mutualist and a follower of Proudhon, the transcendentalist William B. Greene. This star is probably quite related, and is spoken of as being an ever-transcendent ideal, not unlike Proudhon’s concept of perfect societal equilibrium, as when Constance Margaret Hall points out that “Proudhon saw society as a dynamic whole which strove toward equilibrium but which never achieved this state.”[28]

Proudhon also shares much in common with the “holarchy” concept of Ken Wilber, and arguably fits Wilber’s definition of a perennial philosopher (remember, remodernism is calling for a return to the perennial). While speaking of his holarchy approach, Wilber goes on to say, “Interestingly, the perennial philosophy reached the same conclusion, in its own way.” He says,

We may say that [the perennial philosophy] is the core of the world’s great wisdom traditions. The perennial philosophy holds that reality is a Great Holarchy of being and consciousness […][29]

Of course, Ken Wilber was not the first to recognize the holarchic relationship of things. His integral approach was anticipated by Pierre Proudhon, whose sociology takes the internal/subjective and external/objective aspects of the collective and the individual into account in a very similar way, making him, by Ken Wilber’s terms, a wielder of the perennial philosophy, or at least something much like it.[30] Constance Margaret Hall makes the similarity between Wilber’s Integral Theory and Proudhon’s sociology quite clear when she says that (covering the upper quadrants here)

Justice, for Proudhon, was both external and internal to the individual, objective and subjective, an actuality which was coming into being, and an ideal to be achieved through the conscious and unconscious direction and organization of society on a scientific economic basis.[31]

She says that “Proudhon’s concept of justice, which was simultaneously objective and subjective, was Proudhon’s ‘guiding principle’ for both society and for the individual members of society.”[32] In a discussion of justice as it relates to a holon, Proudhon himself says (as quoted by Hall) that

[…] there are two ways to understand the reality of justice, and thus to determine it:

Either by a pressure of the collective being on the individual, the first modifying the second in its image and making out of it an organ:

Or by a faculty of the individual person who, without leaving his conscience, would feel his dignity in his neighbor with the same vivacity as he felt it in himself, and would find himself thus, all in conserving his individuality, identical and complete with the collective being itself.

In the first place, justice is exterior and superior to the individual, whether it resides in the social collectivity, considered as a being in its own right, of which the prime dignity is that of all its members; or whether one puts it even higher, in a transcendent and absolute being which animates or inspires society, and which one calls God.

In the second case, justice is intimate to me, the same as dignity, equal to this same dignity multiplied by the sum of relationships which make up social life.[33]

For Proudhon, every individual was also a collectivity and every collectivity an individual. That is, everything is composed of holons, as Ken Wilber would put it. Shawn Wilbur, despite his postmodernism, correctly paints us a picture of this holon when he says that

Any body or being, Proudhon says, possesses a quantity of collective force, derived from the organization of its component parts. […] The collective force is the “quantity of liberty” possessed by the being. Freedom is thus a product of necessity, and expresses itself, at the next level, as a new sort of necessity. […] Out of [the free absolute’s] encounters, out of mutual recognition, the “pact of liberty” arises […] and a “collective reason,” possessed […] by a higher-order being, which is to say a higher-order […] absolute.[34]

Every individual is also a collective, and every collective an individual, to Proudhon.

Unlike Shawn Wilbur, Ken Wilber does not appear to have been a reader of Pierre Proudhon or the mutualists, perhaps finding them too “insignificant” to be noticed. Nonetheless, and interestingly enough, Ken Wilber has come to many similar conclusions, reinventing mutualism to some extent. One example of this is his approach to governance called “holacracy,” which has many themes commonly found in mutualism. Holacracy has been understood in terms of a holarchy of self-managing teams, and has been posed as an alternative to unstructured consensus and to sociocracy, one of its main rivals. These constitutional and consent-based models of organizational governance have been found appropriate among many cooperative and mutual associations, marking Ken Wilber as a fellow traveler of social economy (in this regard). Of course, this is not to suggest that Ken Wilber is a mutualist or was completely consistent with the mutualist worldview, of which he may have been ignorant, nor to promote holacracy. Some of the similarities between mutualism and Ken Wilber may come from their shared foundations in the pantheistic or emanationist perennial philosophy, which stressed the holarchic nature of the cosmos all along, but some may naturally result from a wide reading of the world. Like Proudhon, Ken Wilber holds to a process philosophy in which there is no end in any Absolute.

In an interview of Ken Wilber, the interviewer says, ‘It seems that a proper integration of Orange and application of Orange to look at Green and figure out the inconsistencies would set people on a track to second-tier consciousness.’ Ken Wilber affirms and then gives a long-winded reply about how we shouldn’t simply revert back to Orange, but that second-tier will integrate the concerns of Orange, such as freedom, back into the equality that Green discovered, thereby balancing those concerns.[35] This says two things to us in this discussion; that Remodernism—a looking back to the unfinished business of Orange— is necessary, and that it will look like the balancing of freedom with equality, which, incidentally enough, is also the project of mutualism.

It should be apparent by now that Ken Wilber’s Integral, Billy Childish’s Remodernism, and Pierre Proudhon’s mutualism belong together on the second tier of Clare Graves and Don Beck’s Spiral Dynamics. The second tier should be composed of integral remodern mutualism. What’s holding us back?

Part 3

The Postmodern Menace in Mutualism

The postmodern menace is being pushed back against in the arts by remodernism, but it has yet to be pushed back by a working class social movement addressing political economy in a coherent manner.

Mutualism has not gotten far under the postmodern paradigm, and this seems quite natural. If mutualism is to move forward, it must be wrestled from infiltration by cultural Marxist intellectuals. Cultural Marxism rests upon postmodernism, and classical liberalism (capitalism) upon modernity, but—as I think I have fairly demonstrated— mutualism must rest atop remodernism. This is completely natural for mutualism, as remodernism is the re-emergence of modernist Radical Enlightenment potential, within which mutualism had historically developed. Unlike the Moderate Enlightenment, the values of the Radical Enlightenment were never fully actualized. [36] In a way, they informed the Moderate Enlightenment, however, which was actualized. The Moderate Enlightenment, nonetheless, was much less radical than the Radical Enlightenment, and was built upon shallower assumptions. Whereas the Radical Enlightenment stressed the need for popular, direct democracy, the Moderate Enlightenment has been associated with the authoritarian oligarchical republics that are common throughout the world now. Radical Enlightenment values differed greatly from those of the Moderate Enlightenment. As such, postmodernism is not an open reaction against the Radical Enlightenment, but against the Moderate Enlightenment, which modernism calls into question as well. Nonetheless, Jonathan Israel, the foremost scholar on the Radical Enlightenment, writes that postmodernism is one of the greatest threats to Radical Enlightenment thinking:

More recently, among the foremost challenges to Radical Enlightenment principles, and one particularly threatening to modern society, was the modish multiculturalism infused with postmodernism that swept Western universities and local government in the 1980s and 1990s. For this briefly potent new form of intellectual orthodoxy deemed all traditions and sets of values more or less equally valid, categorically denying the idea of a universal system of higher values self-evident in reason and equity, or entitled to claim superiority over other values. In particular, many Western intellectuals and local government policymakers argued that to attribute universal validity and superiority over other cultural traditions to core values forged in the Western Enlightenment smacks, whatever its pretensions to rational cogency, of Eurocentrism, elitism, and lack of basic respect for the “other.”[37]

Israel also tells us—speaking of the importance of modern philosophy to contemporary society— that,

While a perplexing notion for us, it seemed perfectly obvious to most contemporaries that “modern philosophy” […] was the chief engine of the revolutionary process. Condorcet, for instance, held that “philosophy” caused the Revolution and that only philosophy could cause the kind of revolution that entails (and yet simultaneously depends on) a rapid, complete, and thorough transformation in thinking about the basic principles of politics, society, morality, education, religion, international relations, colonial affairs, and legislation all at the same time. Although this view remained broadly current from 1789 down to the mid-nineteenth century, later it came to be completely obfuscated by the dogmas of Marxism, which insisted that only changes in basic social structure can produce major changes in ideas, as well as by the kind of dogmatic anti-intellectualism promoted in the 1950s and 1960s by Alfred Cobban and others, and then latterly by Postmodernism. All insisted on the impossibility of intellectual debates and ideas playing a fundamental role in shaping societal change.[38]

Heed Israel’s warning.

At the present, mutualism is under the threat of postmodern analysis paralysis facilitated by postmodernists such as Shawn P. Wilbur, who has more-or-less attempted to monopolize the “online culture” of mutualism. Shawn has a history with cultural Marxism (and online culture), starting with his formal training, which includes a Bachelors in Language (English/Literature) from Oregon State University and a Masters from Bowling Green University in Cultural Studies. Cultural Studies, itself, is a field that has its origins in Critical Theory, which was developed in the cultural Marxist Frankfurt School, and much of postmodern philosophy makes its way into language and literature studies. Ken Wilber claims, for instance, that “By 1979, Derrida was the most-often-quoted writer in all of the humanities in American universities.”[39] But that’s not all, Shawn is also educated in internet culture, and participated in the cultural Marxist Spoons Collective. He has also been affiliated with the Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities, which I take as the likely place he learned both the skill and political importance of archival work. In short, Shawn is a political weapon.

Shawn commonly brings up postmodern philosophy. His neo-Marxist programming seems to keep him from an honest presentation of Proudhon, however. Projecting postmodern philosophy onto Proudhon, a modernist, Wilbur holds that

What [Proudhon did] was a bit peculiar, involving a hijacking of Leibniz in directions that anticipate folks like Gilles Deleuze. The psychological and social physics that is at the center of his mature work on liberty and justice reasons like poststructuralism in places, and I will have some recourse to the vocabulary of the more contemporary continental philosophy as I talk about it.[40]

It sounds like poststructuralism because modernism has all of the insights of postmodernism, which postmodernism simply blew out of proportion. Duh.

This theme of projecting postmodern thinking onto Proudhon carries throughout much of Wilbur’s work, and appears one of his main motivations for taking on the project. Nonetheless, postmodernism is not a popular philosophy among the working class because of its tendency toward empty talking—“obscurantism”—, which working people don’t have time for (but can be intimidated by). Shawn Wilbur claims to be a working person, but he has the privilege—a government-granted monopoly on mental capital (accredited Masters degree)— not to be, if he wants it. Others don’t have this luxury, some on principle, and some because the opportunity was never presented. This is not a small matter, and must be considered with any intellectual who speaks for anarchism (but that’s just “Old Left” modernist reasoning, isn’t it?).

Remember the “cultural wars” that Ken Wilber mentioned earlier? Well, Shawn Wilbur suggests that

There is a strong sense among [postmodern] scholars that it is at the level of language (or at least of ideas and ideologies) that cultural battles are won and lost. This makes deconstructionist readings of “social texts” seem a powerful political tool.[41]

This is said by a man who appears university-trained in this stuff, has lectured in the academy on related matters, and who is playing doorkeeper, archivist, gatekeeper, and maintains a “magisterial tone” in academic books about anarchism costing over $200 (!). Shawn also openly says that “My intuition [is] based in part on some language various places in Proudhon’s work and in part on the connections I’ve been making to other continental thoughts […]”[42] Shawn is, in his work, essentially taking unrelated material from Proudhon (like his “Theory of Property”), comparing it, and then projecting postmodernism onto it. In doing so, he comes up with things that none of the other literature on Proudhon would find agreeable. Let’s have an example, from John Vervaeke, about comparing unrelated material…

John Vervaeke, who is taking on “the Meaning Crisis” (that postmodernism has wrought), suggests that one problem of “the deconstructed mind” is that of equivocation. He says that one can take two different sentences— which use the same word with a different intention, and have perfectly fine meaning on their own—, mix them up, and construct something completely different (in this case, less purposive as well). His example is these two sentences:

Nothing is better than long life and happiness.

And,

A peanut butter and jelly sandwich is better than nothing.

On their own, these sentences confer meaning perfectly well. But Vervaeke continues to put them together in an absurd (absurd being a concept in the postmodern or quasi-existential thought of Albert Camus) manner. He reasons that when together, they say that

Nothing is better than long life and happiness, and a peanut butter jelly sandwich is better than nothing, so— ergo— a peanut butter and jelly sandwich is better than long life and happiness, so you should eat one and then go kill yourself.[43]

John Vervaeke is pointing out here the absurdity of deconstruction. While “nothing” is used in both sentences, and those sentences make sense on their own, putting them together produces an absurdity. This seems to be precisely the method of deconstruction, a method of literary criticism popularized by Derrida. Derrida—whom Shawn is quite familiar with— is known for having challenged that reading is impossible and that meaning is basically non-existent or hypersubjective. If one breaks down a text enough, according to Derrida, its contradictions render it meaningless. Surely, Shawn is aware of this, and it seems evident to me that he employs these efforts. But deconstruction can only go so far.

In his series on “Awakening from the Meaning Crisis”, John Vervaeke points out that language likely developed with much help from the shamans that used to be prevalent in human societies.[44] Through entheogens, ritual practices, and abstinence from socialization, food, drink, or sex, and with the help of beating drums, dancing, and chanting, shamans could induce altered states of consciousness such as the trance, which could create—what Vervaeke may suggest later is a form of—a quantum leap in conception, powered by way of metaphor. Vervaekea points out that many of our words, such as “understand” are not to be taken by their literal meaning (under stand), but have their roots in the kind of metaphorical imagination and sympathy that shamans would help to induce. John points out that the shared space for sharing meaning relied on much shared sympathy. Similarly, Roger Scruton remarks, in his attack on deconstructionism, that

Figures of speech are open to their meaning. They are vivid, immediate, unambiguous. They are used all the time, and indeed clichés are composed of them. A sly fox, a loving heart, a sullen anger, a serious face — all those are figures of speech. Some seem more figurative than others. But they are all figurative (in the literal sense of the term). They transfer a word from the context which provides its meaning to a context where its meaning is exploited in some novel way. You might think that figures of speech must therefore bear a double meaning. But that is not so. The literal meaning is usually lost in the transfer. When I read ‘His heart was in his mouth’, the literal sense of the words does not occur to me. If I understand them literally I shall be guilty of a misreading.[45]

If anything can be counterposed to the kind of sympathy that is needed to exchange real meaning with one another, it is the kind of meaning-destroying represented by deconstructionism, an approach that Shawn has a soft spot for. It is for this reason that Roger Scruton says, playing on the name of Derrida,

I hope I shall be forgiven if I add to this list of destructive words a neologism, the verb ‘to derridize’, derived from ‘to rid’ and ‘to deride’. I shall be dis-cussing the attempt to rid literature of meaning in order to deride the common reader[46]

Deconstructionism is often understood to be hyper-critical, to influence a reading of texts which is swallowed in generalized antipathy. The kind of analytics employed by deconstructionism are subject to the criticism of the philosopher Henri Bergson, who demonstrates in his “Introduction to Metaphysics” that intuition as direct perception is a much more authentic manner of understanding the world than analytical text is. Textual analysis is no substitute for an intuitive reading.

At some point Shawn found Proudhon and noticed superficial similarities between Proudhon and his old friend Derrida, particularly between Proudhon and Derrida’s shared rejection of absolutism. Derrida held that reading is impossible, and Proudhon held that property was impossible… but upon completely different grounds. Derrida was a postmodernist, but Proudhon was a student of the Radical Enlightenment. Evoking Derrida’s deconstructionism, and perhaps announcing his own fated position in regard to the job he will be doing on mutualism (deconstructing it), Shawn Wilbur says,

Ok. Concepts turn on themselves, splinter, mutate, disseminate themselves, go to war, form strange alliances—in short, behave much like the human organizations they inspire. These days we might call this deconstruction. Proudhon called it contradiction—antinomy—by which he meant not simply logical inconsistency, but a productive, pressurized dynamic […] In the antinomy, A and B together look pretty good, despite the fact that neither of them alone seem to offer much. The difference is important, in part because it forces us to focus on a rather different conceptual horizon than we might otherwise.[47]

Shawn here is suggesting that his deconstruction of Proudhon is itself Proudhonian, because he’s offering an antinomy to Proudhon’s thinking (in particular, his “Theory of Property”). Wilbur’s deconstruction and Derridization of Proudhon is deemed his “New Approximation” of which he says that “breaking with the founders is an act of fidelity to the tradition,” while establishing a false dichotomy (“possession” and the property-state antinomy) between Proudhon’s own concepts. He says,

The […] synthesis of communism and property […] presumably ought to be of interest […] But I don’t find much treatment of it, beyond a fairly offhand suggestion in An Anarchist FAQ that the synthesis is “possession.” I’m not entirely opposed to that reading, but, unfortunately, I remain unable to tell precisely what Proudhon means by “possession” in 1840

[The “New Approximation” is] a different kind of response to the possibility of […] Proudhon’s repeated suggestion that there might be a “communist” route to mutuality and liberty, as well as one through the encounter with “property.”[48]

Shawn suggests that, in the end, Proudhon supported a property-state antinomy (which sounds an awful lot like welfare capitalism administered by the techno-managerial elite):

“Property” itself never really appears as anything but a simplist, or one-sided, concept. Its incorporation in a non-simplist property-state antinomy is an advance […], but inevitably one which tends to focus us on one part of a complex problem, to the exclusion of other parts.[…] Proudhon attempted [“to focus on some higher-order concept, such as social justice or mutuality, which incorporates property as one of its aspects”], with somewhat mixed results, but he explicitly suggested the possibility of [“attempting to rethink property in some other way”]. In the “New Approximation” […] I’m […] starting to address individual property in its “collective” aspects, in order to avoid some confusions that seem to be “built in” with Proudhon’s approach.[49]

Shawn’s go-to document for making his arguments is Proudhon’s “Theory of Property,” which Wilbur was apparently the first or latest to translate (his translation appears in an anthology of Proudhon’s works). But this document is not taken too seriously by other scholars of Proudhon and of anarchism, such as Ian MacKay. In Property is Theft!, the collected anthology of Proudhon’s works, “Theory of Property” appears as a mere appendix. Why? MacKay suggests, as a preface to Wilbur’s translation, that it was posthumously published and unfinished work that Proudhon himself had laid aside to work on more important things that he actually did finish and publish. Further, he suggests that “What becomes clear from this work is that there is no significant change in Proudhon’s perspective on property and possession.”[50] In the same anthology, it is said that

After 1850, Proudhon started to increasingly use the term “property” to describe the possession he desired. This climaxed in the posthumously published Theory of Property in which he apparently proclaimed his whole-hearted support for “property.” Proudhon’s enemies seized on this but a close reading […] finds no such thing[51]

Proudhon is nonetheless an easy target for deconstruction. Ian MacKay holds that

In terms of the language he used, Proudhon was by no means consistent. Thus, we have the strange sight of the first self-proclaimed anarchist often using “anarchy” in the sense of chaos. Then there is the use of the terms property and the state, both of which Proudhon used to describe aspects of the current system which he opposed and the desired future he hoped for.

[…]

This changing terminology and ambiguous use of terms like government, state, property and so forth can cause problems when interpreting Proudhon. This is not to suggest that he is inconsistent or self-contradictory. In spite of changing from “possession” to “property” between 1840 and 1860 what Proudhon actually advocated was remarkably consistent. The caveat should be borne in mind when reading Proudhon and these ambiguities in terminology should be taken into consideration when evaluating his ideas.[52]

Shawn Wilbur has no real grounds to be making such a fuss about “neo-Proudhonian” sociology. Not only were most of his valid ideas already expressed in thinkers like Constance Margaret Hall, but Shawn’s postmodern nonsense has no basis in reality. Upon a wide reading of both Proudhon and secondary sources, one gets a clear image that Shawn Wilbur just does not fit into. The “New Approximation” he puts forth is a mythical creature, a dragon, whose head must be lopped off as it attempts to grow into a hydra. But, as Shawn Wilbur says,

It is not nearly sufficient […] to try to discover truth by gallivanting about slaying falsehoods. At a minimum, we have to be willing to poke around in the entrails of the dragons we bring down. More than likely, though, we’re going to need some of those suckers alive, at least for awhile.[53]

So, let’s do some poking around in the entrails of the dragon I am slaying here. But, Shawn is right, let’s keep it around for some of his archival work, which is useful enough. Even appreciated (thank you, Shawn).

Shawn acts as the self-designated doorman of mutualism, “greeting” (if you can call it that) all of the new folks who poke their heads into the movement. He has established himself as the administrator on both Facebook and on Reddit, social media sites where mutualists appear the most active.[54] He commonly replies to posts, typically to demonstrate some sort of perceived flaw in a fellow mutualist’s understanding, and one that usually amounts to not using Shawn’s preferred language, or which is too assertive for Shawn’s tastes. Shawn would appear to prefer that his fellow mutualists adopt a religious, postmodern reading of Proudhon, such as his own, and mold their perspectives to whatever new insight is found about Proudhon (so long as it does not imply anti-Semitism or misogyny, etc.), and to be sure to use key phrases and terminology out of the book, rather than to put mutualism into one’s own words. One user says, “everytime I think I’ve got a ‘what is mutualism’ take, I’m wrong, or at least confusing a mix of mutualisms.” This, after forfeiting his cognitive sovereignty to Shawn Wilbur, tagging him to answer in the user’s place. That is, the user tagged Shawn, explaining that his reason for doing so was that he never seems to get it right.[55] This is not an uncommon sort of response to interacting with Shawn.